3rd Year of PPH programme between India and Japan- Starting December 20, 2021

No Claim Permissible On Relinquished/Assigned Trademark

Protection of Memes and Copyright

Breach of confidentiality by ex-employee vis-à-vis IP infringement

Cognizance of Offences under Section 63 of Copyright Act

Because You(r trade marks) are Worth It!

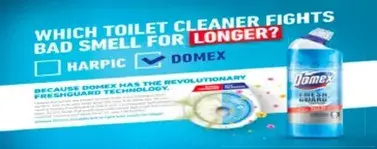

The Free flow of commercial information or overstepping the grey area of advertising?

Due Diligence a Guide to Start-up Fundraising

India and Japan PPH programme – 3rd year Starting December 20, 2021

By Lucy Rana and Renu Bala

The IPO will again start accepting PPH applications from 20 December, 2021

Bilateral relations between India and Japan have been very strong over the last few years, and the same is constantly improving in all dimensions with the passage of time, ranging from trade to strategic partners in defense, and also, in the field of intellectual property rights.

On November 2019, the Union Cabinet had approved the proposal for adoption of Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) programme by the Indian Patent Office under the Controller General of Patents, Designs & Trade Marks, India (CGPDTM) in collaboration with Patent offices of various other countries and regions, the details and benefits of the programme can be viewed[1]. Guidelines for Patent Prosecution Highway were issued for addressing the procedures to be followed by Applicants, the overview of the guidelines can be viewed [2].

India’s first Patent Prosecution Highway Pilot Program commenced on November 21, 2019 between the Japan Patent Office (hereinafter referred to as ‘JPO’) and the IPO for an initial period of three years.

The second year of the pilot program again commenced from March 09, 2020, and the number of requests were limited to 44, the details of the notification can be viewed[3].

Recent Update – Continuation of PPH between India and Japan

As per a recent notification on the official website of Indian Patent Office (IPO), the IPO will start accepting Form 5-1 under Chapter 5 of the PPH Guidelines for the third year of the pilot program with effect from December 20, 2021. The number of requests will be limited to 100 per year and will be on first come first serve basis. Further, there is a limitation of 10 PPH requests to IPO per year per applicant, who filed patent application either alone or jointly with any other applicant.

Further, the request for assigning special status for expedited examination under the PPH is required to be filed online in the prescribed Form 5-1. The applicant/ authorized agent can file the request for expedited examination in Form 18A only after the request is accepted by IPO for assigning special status. The decision on Acceptance/Rejection/Defect noticed will be communicated to the Applicant/Authorized agent through email as well as message on e-filing portal.

In case of defects in Form 5-1, the applicant will be provided an opportunity to rectify the defects within 30 days from the issue of notification of defects by IPO.

Additionally, the Procedure Guidelines to file a PPH request under the Patent Prosecution Highway Pilot Program between the Indian Patent Office (IPO) and the Japan Patent Office (JPO) can be accessed by clicking here.

[1] https://ssrana.in/articles/india-patent-prosecution-highway-gets-cabinets-approval/

[2] https://ssrana.in/articles/india-an-overview-of-procedure-guidelines-for-patent-prosecution-highway/

[3] https://ssrana.in/articles/pph-india-latest-news-accepts-new-requests-march-9-2020/

On The Relinquished/Assigned Trademark No Claim Permissible

By Ananyaa Banerjee and Isha Tiwari

Ampa Cycles Private Limited vs. Jagmohan Ratra

Introduction

Assignment of a trademark is a process, whereby a person, “the assignor” transfers rights in the trademark or benefits to another person “the assignee”. Indian trademark law permits assignment of registered as well as unregistered trademarks, with or without the goodwill of the business concerned1. The Hon’ble Delhi High Court delivered a noteworthy ruling in M/s Liberty Footwear Company vs. Liberty Innovative Outfits Limited2, wherein it was held that non-registration of an assignment deed on account of delay on part of the Trade Marks Registry is not fatal to the assignment rights of an assignee.

The Division Bench of Hon’ble Delhi High Court in the recent case of Ampa Cycles Private Limited vs. Jagmohan Ratra3 has held that once a trade mark is relinquished by a party then he cannot claim any right therein.

Relevant facts

- The first use of subject trademark AMPA in respect of bicycles and tricycles dates back to the year 1991 by the partnership firm, M/s Four Diamonds which was initially formed in 1983 by Jagmohan Ratra (hereinafter as “the Respondent/Plaintiff”) and Hari Dutt as its partners]. On March 30, 1992, Ampa Bikes Private Limited (hereinafter as “ABPL”) was established with the Respondent/Plaintiff and the firm M/s Four Diamonds as its shareholders.

- The first trademark application for AMPA in Class 12 was filed on June 21, 1995 with a user claim dating April 01, 1992 by ABPL. The said application was subsequently abandoned in 2002.

- After a dispute arose, M/s Four Diamonds dissolved on August 01, 2003, with Hari Dutt Sharma exiting the firm vide dissolution deed dated August 01, 2003 and the Respondent/Plaintiff continued business as sole proprietor of Four Diamonds. The Respondent/Plaintiff transferred his shares in the company ABPL to Hari Dutt Sharma towards settling the dues of the retiring partner. The Respondent/Plaintiff was to continue to use the trade mark AMPA and all other assets and goodwill were to be transferred to Hari Dutt Sharma. Moreover, the use of the trademark AMPA was to be continued by the two parties in the following way:

| Respondent/Plaintiff | ABPL |

| Will use AMPA trademark in respect of cycles up to 14 inches in tyre radius. | Will use AMPA trademark in respect of all cycle models more than 14 inches in tyre radius after 3 years from the date of the deed. |

- In 2013, the company ABPL was struck off from the Register of Companies, and ceased to exist. However, the trade mark AMPA was still being used by the Respondent/Plaintiff for cycles. The signatories ABPL viz. Hari Dutt, Nishtha Sharma and Ajay Kumar Bawa entered into an assignment deed for trademark AMPA in the name of Ajay Kumar Bawa for a consideration of INR 1,00,000 on January 03, 2013.

- Ampa Cycles (P) Limited (hereinafter as “the Appellant/Defendant”) was incorporated on June 05, 2018 for manufacturing cycles, tricycles and bikes under the brand name AMPA by Ajay Kumar Bawa, Anmol Bawa and Pranav Sharma, as its directors. The Appellant/Defendant filed application for the trademarks AMPA,

(opposed by the Respondent/Plaintiff ) and the logo

(opposed by the Respondent/Plaintiff ) and the logo on November 15, 2018 a proposed to be used basis in Class 12 and subsequently filed an application for registration of trademark AMPA on September 07, 2020.

on November 15, 2018 a proposed to be used basis in Class 12 and subsequently filed an application for registration of trademark AMPA on September 07, 2020. - The Respondent/Plaintiff filed application for the trademark

, interestingly with a user claim of April 14, 2011, and subsequently this was opposed by the Appellant/Defendant .

, interestingly with a user claim of April 14, 2011, and subsequently this was opposed by the Appellant/Defendant .

- The Learned Single Judge of Hon’ble Delhi High Court allowed the I.A. for a grant of interim injunction under Order 39 Rules 1 and 2 of CPC in favour of the Respondent/Plaintiff and dismissed the I.A. under Order 39 Rule 4 of the Appellant/Defendant vide order dated March 17, 20214.

Relevant Contentions of the Parties

The counsel for the Appellant/Defendant argued that the trademark AMPA is being used by the Appellant/Defendant by virtue of the dissolution deed dated August 01, 2003, whereas the Respondent/Plaintiff had relinquished his rights and cannot subsequently challenge the said use, after admitting to the same, merely on the grounds that trademark applications were filed on a ‘proposed to be used’ basis.

On the contrary, the counsel for the Respondent/Plaintiff argued that under the dissolution deed ABPL is free to use the trademark AMPA for all cycle models of more than 14 inches after a period of 3 years. The company ABPL was struck off from the Register of the Companies in 2013, all association with the trademark AMPA ceased as well.

Court’s Observations and Ruling

The Division Bench of Hon’ble Delhi High Court was presided over by Justice Rajiv Sahai Endlaw and Justice Amit Bansal, relied on the precedent set up by the Hon’ble Apex Court in Ramdev Food Products Pvt. Ltd. vs. Arvindbhai Rambhai Patel & Ors.5. The Hon’ble Court reiterated that a party cannot be permitted to claim rights in a trademark once has expressly waived its rights in the said mark, shining light on the legal principle what cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly. As per the dissolution deed, the Respondent/Plaintiff had renounced his right to use the trademark AMPA in respect of cycles with more than 14 inch radius in favour of Hari Dutt. The Court’s main emphasis was not on determining the validity of the assignment rights, but rather the unequivocal consent to the terms of dissolution deed, which neither were disputed nor were ever modified, revoked or amended at any point in time by either of the parties. Even non-use of a trademark till its assignment has been ruled out as a ground for the party that has voluntarily relinquished its rights in the said trademark, to claim any rights therein. The Hon’ble Court observed that the Respondent/Plaintiff has given a complete waiver in favour of Hari Dutt Sharma for using the trademark AMPA, he is estopped from preventing the usage of the said mark by Hari Dutt Sharma or his successor or assignees.

Another interesting observation to connote, particularly procedural, is that when claiming statutory rights by way of trademark application, it is irrelevant that the subject applications are filed on ‘proposed to be used’ basis without any mention of assigned rights.

Due credence was also given to the substantial goodwill and reputation collated by way of sales by the Appellant/Defendant since its use in 2018, which tilted the balance of convenience in its favour against an order of injunction.

Analysis and Conclusion

Definition of ‘waiver’ as per the Black’s Law Dictionary, has been defined as the voluntary relinquishment or abandonment of a legal right or advantage6. In Ramdev Food Products supra, waiver was defined as the abandonment of a right in such a way that the other party is entitled to plead the abandonment by way of confession and avoidance if the right is thereafter asserted, and is either express or implied from conduct.

In view of assignment, the Court in M/s Liberty Footwear Company supra had termed voluntary non-registration of assignment deed as a waiver. Keeping in view the aforesaid definitions, it is abundantly clear that the Respondent/Plaintiff voluntarily agreed to use the trade mark AMPA jointly with Hari Dutt and there was no condition precedent to such assignment in the dissolution deed. Once the Respondent/Plaintiff has given a complete waiver in favour of Hari Dutt Sharma from using the trade mark AMPA, he is estopped from preventing the usage of the said mark by Hari Dutt Sharma or by his successors/assignees.

Whereas, the Appellant/Defendant in the present case had simply filed applications for AMPA formative trademarks on a ‘proposed to be used’ basis, post its company’s incorporation in 2018, rather than claiming an earlier adoption by way of assignment. In fact, the Appellant/Defendant’s pro-activeness can also be evidenced from its decision to oppose the Respondent/Plaintiff ’s application for the trademark ![]() (which was interestingly filed with a questionable user claim itself). Therefore, the Division Bench of the Hon’ble Court has rightly opined that the Respondent/Plaintiff’s claim itself is weak when it comes to claiming singular proprietary rights over AMPA, and though there is underlying importance to filing trademark applications with correct details, an applicant’s bonafide rights needn’t suffer for procedural objections. In these circumstances, the appeal of the Appellant/Defendant was allowed and order of the Learned Single Judge was set aside and interim order was vacated.

(which was interestingly filed with a questionable user claim itself). Therefore, the Division Bench of the Hon’ble Court has rightly opined that the Respondent/Plaintiff’s claim itself is weak when it comes to claiming singular proprietary rights over AMPA, and though there is underlying importance to filing trademark applications with correct details, an applicant’s bonafide rights needn’t suffer for procedural objections. In these circumstances, the appeal of the Appellant/Defendant was allowed and order of the Learned Single Judge was set aside and interim order was vacated.

[1] CS (COMM) 637/2019; https://ssrana.in/articles/non-registration-of-assignment-deed-india/

[2] FAO(OS) (COMM) 75/2021

[3] I.A. No.12625/2020 and I.A. and I.A. No. 1394/2020 in CS(COMM) No.569/2020

[4] (2006) 8 SCC 726

[5] Bryan A. Garner, Black’s Law Dictionary (8th Edn., Thomson Reuters 2009)

Memes and Copyright Protection

By Ananyaa Banerjee and Soumya Sehgal

While “Social” Media was initially meant to bridge the distance between people all over the world and build relationships, the same has quickly evolved as a great platform to share content, ideologies etc. Presently, the entire social media landscape contains pictures, videos or media of any sort with a humorous or relatable context. In fact, the usage of social media platforms has gradually transitioned from personal interaction to sharing of memes. While the common man may not invest a lot of thought behind the creation and/or consequence of a meme, the same does entail a certain amount of liability as discussed in detail in this article.

TYPES OF MEMES AND PROTECTION UNDER COPYRIGHT

A meme can be of two types: The first type is where the person creating the meme (commonly known as a “memer”) uses pictures or videos from an original content to create a meme. For example the famous character of ‘Chandler Bing’ from the popular television show ‘Friends’ is used by many memers to depict sarcasm.

In this case, the copyright in the picture of ‘Chandler Bing’ would lie with the producers of the show. The memer, not being the creator of the picture, is copying it and using the same to depict his content. Therefore, if the producers of the show can prove that the meme infringes upon their copyright, they may be able to stop it from being shared.

The second type is where the memer has created the meme with pictures and videos, the underlying copyright in which belongs to himself. A meme like this may be defined as an artistic work made by one’s own talent, labour, and judgement, etc which does not infringe on an existing copyright. However, sharing/reproduction of such kind of memes without prior approval of the memer may be considered copyright infringement, and the creator of the “memed” picture may be able to restrain others from using it without permission. The liability of the copyright infringement of the memer depends upon the images or videos used by that person.

The key question here is whether the meme was illegally appropriated by utilising a substantial or material portion of the original copyrighted work, or whether an essential aspect of the artist’s original vision was substantially reproduced. The physical features of the allegedly unauthorized copy, as well as the medium of expression, may change, along with certain aesthetic variations. However, if there is any substantial imitation or copying of the original work, then the meme will be deemed to be an infringement.1

However, it is also important to note that obtaining the permission or consent of the owner of the copyrighted work for creation of a meme may not always be feasible, and in most of the situations, the owner of the original work may not even be known.

PROTECTION UNDER FAIR USE ENSHRINED UNDER THE COPYRIGHT ACT, 1957

The “fair use” doctrine comes at play as a legitimate defense in cases of copyright infringement. The Copyright Act, enlists four factors to determine if such use of copyrighted work is “fair” or not, though none are determinative2.

First Factor: Whether the purpose and/or use of the copied work is of a commercial nature. In most cases, memes are usually created for a recreational and entertainment purposes and there is no element of any commercial use or economic gain. Therefore, most of the memes satisfy the first factor of fair use doctrine. However, if any meme is created to generate revenues or for any promotional purposes without the required permissions from the owner of the copyright work, the same would constitute commercial exploitation and therefore, the memer in such cases cannot claim any defense under the doctrine of fair use.

Second Factor: Nature of the copyrighted work- Almost every meme is taken from an already published material so as to increase its relatability factor. In such case, the original author has exhausted his right of first public appearance and the memer can claim a defense under fair use doctrine. However, the defense under the fair use doctrine shall not be applicable if the memer borrows content from an unpublished work.

Third Factor: The amount and substantiality of the copyrighted work used- If the memer just takes a single joke or still from an original work such as a television show or a movie, then, substantial amount of the original work is not copied, and fair use doctrine can be applied. However, if the original work from which the content is borrowed is a single photograph or any other single frame visual artwork, then it would be considered as borrowing the entire artistic work and constitute an infringement.

Fourth Factor: Effect on the potential market- As stated above, memes are usually made for recreational purposes and no commercial gain is expected out of it. Each meme, even though created from a common original work, is unique. Further, even the target audience for the ‘original work’ and ‘memes’ are most often different and it rarely affects the viewership of the original works. Therefore, memes satisfy the fourth factor of fair use doctrine.

EXECPTION TO THE APPLICABILITY OF FAIR USE DOCTRINE

However, as a word of caution, if a meme is intended to harm the society or if it violates the Right to Privacy enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, then there is no defense available in favour of the meme creator. In fact, the memer, cannot even exercise his defense of Right to freedom of speech and expression enshrined under Article 19 of the Constitution of India3 in such cases.

In a plethora of cases, the Indian courts have held that the right to criticize or imitate a person through memes is not exclusive and is limited to the point where the rights of the other person are not affected. For example, recently, BJP’s Youth Wing leader Priyanka Sharma (Defendant) was asked to apologize to the prominent leader and the Chief Minister of West Bengal Ms. Mamata Banerjee, for defaming her character, by posting a morphed image of hers on social media. The Supreme Court did not give any leverage to the Defendant, even though she argued that she did not “create” the meme and only “shared” it for humour. The Supreme Court held that Freedom of speech and expression cannot be denied at any time, but faces its end when such freedom violates the rights of other people.4

The sharing of such defamatory meme by the defendant has been stopped by the court. However, it is the meme creator who should be identified at the first instance so that the meme can be stopped from being shared to a large section of society. According to The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, if the meme is against the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States etc., then the meme creator/first originator can be identified by the intermediaries (Facebook, Instagram etc) by a judicial order passed by a court of competent jurisdiction or other competent authorities mentioned in Rule 4(2) of the said rules.5

One may conclude that the use of memes on social networking sites is generally ‘fair use’ with exceptions as stated above. The use of this doctrine requires a case to case analysis of facts; no blanket protection can be granted. The issue regarding fair use of memes has not been subjected to litigation till now in India.

COMMERCIAL USE OF MEMES

It is understood that commercial use of a meme would not come under the ambit of fair use doctrine, and the owner of the original copyrighted work can claim an infringement action against the meme creator. However, it is pertinent to note that if a corporation is creating its own meme without copying any original artistic work, then circulation of the same by third parties, even if done for commercial purposes, does not call upon any copyright infringement. Businesses are interested in utilising memes as a promotional tool. In fact, many companies have made meme marketing very essential part of its marketing campaign.

For example, Zomato has used photograph of the famous Pakistani Comedian Moin Aktar as Harmonium Chacha, for promoting and marketing purposes. In this case, the owner of the copyrighted work in the picture of the Harmonium Chacha are the producers of the film, and Zomato has used the same to promote its business.

On a day to day basis we see many companies/organizations, actively promoting their business through memes. The memes often refer to famous movie characters or pictures which have gained popularity. This kind of positive promotion helps the organization in getting more publicity, and also the owner of the original copyrighted work in getting more viewership of the said clip/scene/movie. Therefore, if the company/organization duly takes the necessary permissions from the owner of the original copyrighted work while creating memes, then both the company as well as the owner of the copyrighted work can gain benefits from the same. The same would give a positive promotion to both the parties, thereby creating a symbiotic relationship. Besides, the companies can also avoid unnecessary legal actions by relying upon such mutually beneficial relationship.

There are instances (even though rare) where the owners of the original artistic works have diligently taken action against the copyright infringement. The celebrity cats, Keyboard Cat and Nyan Cat have protected their intellectual property rights by winning a lawsuit against corporate giant Warner Bros6. In this case the owners of the original copyright work have successfully sued Warner Bros and 5th Cell Media for using their creations in the game “Scribblenaughts” without their permission. The owners of the original copyright work were given compensation for their work, and the famous felines will continue to appear in the game.

In yet another case, Grumpy Cat Limited sued Grenade Beverage for using the cat’s iconic image to market its new cappuccino drink, Grumppuccino without their permission. Grumpy Cat Limited has successfully won the lawsuit.7

MEME-OLOGY LITIGATION IN INDIA VIS-VIS OTHER COUNTRIES

Till date, India has not witnessed any meme-ology litigation. In the United States of America, the jurisprudence pertaining to parody such as memes etc. is almost the same as that of India. Even USA recognizes the parodies within the ‘fair use’ exception, if the meme satisfies the four statutory factors as laid above in the present article.

United Kingdom has implemented the EU Copyright Directive, which provides exceptions to caricature, parody and pastiche.8 Similar to the Indian and USA laws, even UK protects the memes under the doctrine of fair use/dealing, provided the meme is not used for commercial purposes. Section 30A of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 19889 in UK protects caricature, parody and pastiche under fair dealing.

Further, several countries including India have come up with intermediary guidelines to be followed by social media websites such as Facebook and Instagram, whereby they are instructed to maintain a strong surveillance on any uploaded content to ensure the protection of rights such as the right to privacy and protection against defamation. In India “The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021” were recently enacted by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, which mandate that intermediaries such as Facebook, Instagram etc., to block the access of any unlawful information within 36 hours upon an order from the court, or the government. Elsewhere, European Union has come up with the EU Directives for Copyright, Article 1710 of which prescribes that, information service providers that store and provide information to public at large have to ensure the rights of the rightholders in protecting their content on such platforms.

CONCLUSION

A meme should serve the purpose of fun and entertainment to the audience without violating rights of any individual and should not be created for the motive of commercial exploitation. A copyright infringement occurs when proper authorization and consent from the copyright owner is missing on the part of the creator of such a meme. It is advisable for young creators to seek proper approvals from the owners of the work prior to utilising the same. Creation of meme for amusement is fine but if used for the purpose of business or advertising one should procure necessary consents and license from the copyright owners to avoid facing any kind of legal liability.11

[1] Aishwaria S Iyer, Wbnujs, Kolkata And Raghav Mehrotra, Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat, A Critical Analysis of Memes and Fair Use

[3] https://thedailyguardian.com/analysing-copyright-issues-associated-with-memes-in-india/

[4] https://blog.ipleaders.in/memes-study-defamation/#_ftn5

[5] Rule 4(2) of The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

[6] Charles Schmidt & Christopher Orlando Torres v. Warner Bros Entertainment CV 13-02824

[7] https://theweek.com/articles/459512/7-internet-memes-who-sued

[8] Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society, Article 5(3)(k)

[9] Section 30A, Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

[10] DIRECTIVE (EU) 2019/790 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 17 April 2019

on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC, Title IV, Article 17.

[11] https://thedailyguardian.com/analysing-copyright-issues-associated-with-memes-in-india/

A. Sandhya Parimala, Junior Associate at S.S. Rana & Co. has assisted in the research of this article.

Related Posts

Ex-Employee’s breach of confidentiality in infringement of IP

By Priya Adlakha and Rima Majumdar

It is generally a prudent practice of corporations to have in place confidentiality clauses in their agreements/contracts with employees or agents, so that anything done by the employee/agent during the tenure of their association which adds to the intellectual property of the corporation, remains vested in the corporation even after the termination of such employment/association.

However, a common trend which emerges out of this is organisations trying to hamper the business of their competitors by instituting IP infringement suits, on the pretexts (broadly) that an ex-employee has shared their confidential information with their new employer and this amounts to an infringement of their IP- be it trade secrets, copyright, design, patent, trade marks etc. There have been cases where an ex-employee of an organisation has started up a new business under the name and style of its previous employer, thereby giving the impression that they may still be connected with such former employer.

Through the present article, we aim to discuss what the law has had to say about suits arising out of such situations, and the judgements courts have laid down over the years under IP infringement lawsuits, wherein the principal subject matter was infringement by an ex-employee.

POSITION OF LAW REGARDING IP INFRINGEMENT BY EX-EMPLOYEES

Kerly on Law of Trade Marks and Trade Names, Thirteenth Edition (2001) in Chapter 14 paragraph 90 states that a partner or employee who has left a well-known firm and set up a similar business of his own is entitled to advertise his former connection, but must take care to do it so as not to suggest that the connection is still existing between them and him, or that they have ceased to carry on business and he is their successor. Further in paragraph 201 of that chapter, Kerly has warned that an injunction would be granted if such business was calculated to lead to the belief that it was an agency or department of the claimant company.1

This would mean that, otherwise than in a case of intended misdirection, an erstwhile partner or employee can advertise their former connection, provided they take care to show that it is only history and not a current agency or branch of the other business firm. However, this isn’t always the case, and more often than not, courts are faced with a situation where an ex-employee leaves and either starts their own business, using the previous employer’s intellectual property, or joins a competitor and discloses confidential information pertaining to the IP of his previous organisation.

In Glenny v. Smith (1865)2 Drew & Sm 476, Defendant was an employee of the Plaintiffs, Thresher, Glenny & Co. After leaving their service he opened a shop in Oxford Street and placed on the shop windows the words “from Thresher & Glenny”, the word ‘from’ being in very small letters. Injunction was granted to restrain the Defendant from using the name of the Plaintiffs.

In Charan Dass v. Bombay Crockery House 1984 PTC 102 (Del), the Defendants were the retailers for stoves manufactured by the Plaintiffs under the Plaintiffs’ registered trade mark PERFECT and SWASTIK PERFECT. The same continued upto 1981. It was in the year 1981 that the Defendants started manufacturing their own stoves under the trade marks ‘TRISHUL PERFECT’ and ‘VIJAYA PERFECT’. The court held that, because of the Defendant’s previous role as a seller of the Plaintiff’s goods, the act of the Defendant in selling their similar goods under a similar trade mark s not a bona fide act and amounts to passing off their goods as those of the Plaintiffs, and therefore the court granted the Plaintiffs an ad-interim injunction.

In the case of Velcro Industries v. Velcro India Ltd., 1993 (1) Arb. LR 465 a learned Single Judge of the Bombay High Court rejected a contention made on behalf of the Defendants that they are entitled to continue use of Velcro as a part of their corporate name because they have independently developed a reputation in India. It was noted that the defendants in that case were merely acting as licensees and even if the agreement between the parties did not provide that on termination of the license, the defendants would cease to use Velcro as a part of their trade name, that would make no difference, since the trademark Velcro is a registered trademark of the plaintiff and to allow the defendants to use it as a part of their corporate name is to permit them to give an impression to the public that they are still connected with or have a license from the plaintiffs.

In Burlington Home Shopping Pvt. Ltd. vs. Rajnish Chibber, 61 (1995) DLT 6 a Single Judge of the Delhi High Court was concerned with an application for interim relief in a suit by a mail order service company against its ex-employee for injunction restraining breach of copyright and confidentiality, pleading that compilation of addresses developed by devoting time, money, labour and skill, though the sources may be commonly situated, amounted to a `literary work’ wherein an author has a copyright. Finding that the database available with Defendant was substantially a copy of the database available with and compiled by the Plaintiff, interim injunction was granted.

In the case of J.K. Jain and Ors. Vs. Ziff-Davies Inc. 2000 (56) DRJ 806, where the subject matter of the suit were four titles used with respect to magazines, the basis of the Plaintiff’s suit was that the Defendants were only publishing their computer magazine under the trade mark “PC MAGAZINE INDIA” under a license agreement. As per the license agreement, the Defendants had specifically agreed and acknowledged the copyright and trade marks of the Plaintiff, not to exercise its rights under the agreement or otherwise claim any right or interest in trade marks beyond the rights bestowed by the agreement. After the license was terminated, the Defendants started publishing four magazines, contrary to the terms of license. The Court, on the issue of whether the words “PC”, “WEEK”, “MAGAZINE”, “COMPUTER”, “SHOPPER”, “USER”, “INTERNET”, are descriptive or general words, observed that as an ex-licensee, Defendants were estopped from claiming that the mark was descriptive since the Defendants, under the terms of the license agreement were unable to challenge the proprietary rights of the Plaintiff’s trade mark or trade name on any ground. It was held that after termination of the license the very act of the Defendant in publishing the four titles is contrary to the terms of the licence.

In the case of Sanofi India vs. Universal Neutraceuticals, 2014 the Delhi High Court was faced with a case wherein the Defendant company had been formed by the ex-employees of the Plaintiff company, and the Defendants were in exactly the same business as that of their previous employer, operating under the name and style of Universal Neutraceuticals Pvt. Ltd, selling neutraceutical products by adopting the same trade dress as that of the Plaintiff’s. The mark UNIVERSAL was the registered trade mark of the Plaintiffs. The Court in this case held that “The use of the mark UNIVERSAL by the Defendant company, that has been formed by ex- employees of Plaintiff No.2, would cause irreparable loss and injury to the Plaintiffs, in case the interim order is not passed.”

In the case of Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. v Rajesh Bansal & Ors, MANU/DE/2436/2018 the court ordered the Defendant to pay up punitive damages in a suit for patent infringement, due to the reason that the Defendant was an ex-employee of the Plaintiff’s, who knew about the specifications of the Plaintiff’s invention, which was a method for decoding contents stored on optical storage media, which is a function employed in a DVD player. The Defendants manufactured DVD players under their own brand, but used the Plaintiff’s patented method in it. After trial, the Court was satisfied that it was a fit case of patent infringement and that the Defendants were using the patent of their ex-employer with impunity.

Last year in 2020, in the case of Bennett Coleman & Co. Ltd. vs Arg Outlier Media Pvt Ltd & Ors, MANU/DE/1918/2020 the Delhi High Court was faced with the issue of whether the Defendants’ use of the mark THE NEWSHOUR and NATION WANTS TO KNOW was an infringement of the Plaintiff’s prior used and registered trademarks THE NEWSHOUR and THE NATION WANTS TO KNOW. It was the case of the Plaintiff that the Defendants were ex-employees of theirs, and after resigning from their employment, they had started their own news program and started using the impugned marks/taglines of the Plaintiff on their news channel. After careful deliberation, the Hon’ble Court held that “merely adding some prefixes or suffixes to the trade mark NEWS HOUR, in my opinion does not help the defendants to claim that the mark which is being used by the defendants is not deceptively similar to that of the plaintiff. The marks which are being used by the defendants, namely, ARNAB GOSWAMI’s NEWSHOUR, ARNAB GOSWAMI’s NEWSHOUR 9, etc. prima facie would be deceptively similar to the mark of the plaintiff THE NEWS HOUR. The plaintiff is entitled to relief on this account.”

Conversely though, in the case of Pompadour Laboratories v. Stanley Frazer (1966) RPC 7, where the Defendants had formerly been manufacturing hair lacquer for the Plaintiffs, used the message “Frazer Chemicals have manufactured hair lacquer for Pompadour Laboratories Ltd. for several years” on their goods and advertisements, it was held that this did not amount to an assertion that the Defendants’ goods were the goods of the Plaintiffs, and the Plaintiffs were unsuccessful in restraining the Defendant from their chosen representations.

In Star India Pvt. Ltd. Vs. Laxmiraj Seetharam Nayak 2003 SCC OnLine Bom 27 it was held that everyone in any employment for a certain period of time would come to know certain facts and information without any special effort; all such persons cannot be said to know trade secrets or confidential information and that every opinion or general knowledge of facts cannot be labelled as trade secrets or confidential information. It was further held that if such knowledge is called “trade secrets”, or secret, then the term would lose its meaning and significance. It was held that the basic nature of the business dealings of the plaintiff in that case with its advertisers would be openly known and cannot be called a trade secret or confidential information; the rates of the advertisements are within the public domain and every businessman generally knows the rates of his rivals; the concerned people know the rates of the advertisements; unless they are told the rates and other conditions of the advertisements, no business transaction can be done; such matters are not even open secrets. Similarly it was held that fixation of rates etc. depends on a number of factors including the popularity, in that case of T.V. serial and the time-slots of the display of such T.V. serials and mere use of the words ‘strategies’, ‘policy decisions’ or ‘crucial policies’ repeatedly in all the items does not acquire the position or character of secrecy. It was held that there was nothing on record from which it could be inferred that the defendant had come to know any trade secrets or confidential information concerning the plaintiff company and its business especially when the trade secrets and the confidential information were not even spelled out.

Similarly, in the case of Navigators Logistics Ltd. vs. Kashif Qureshi & Ors., MANU/DE/3355/2018 a Single Judge of the Delhi High Court was faced with a case wherein the Plaintiff had sued its ex-employees for copyright infringement and breach of confidentiality for stealing data concerning the Plaintiff’s clients. The Court however held that “even if list compiled/prepared by the Plaintiff of its customers/clients with contact persons/numbers were to qualify as a original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works (it cannot possibly be a cinematographic film or a sound recording), copyright will not vest therein unless the said list has been published or unless the said list, if unpublished, is authored by a citizen of India or domiciled in India.” Therefore, the Plaintiff in this case had not made out a case for being granted permanent injunction.

it is pertinent to note that in suits for infringement of IP, where the Plaintiff has taken the stance of breach of confidentiality or breach of contract by an ex-employee, the courts have had varied opinions while considering whether to grant injunctions or not.

In Ambiance India (Private) Ltd. Vs. Naveen Jain 2005 SCC OnLine Del 367 the Delhi High Court held that written day to day affairs of employment which are in the knowledge of many and are commonly known to others cannot be called trade secrets. It was further held that trade secret can be a formulae, technical know-how or a peculiar mode or method of business adopted by an employer which is unknown to others. It was further held that in a business house, the employees discharging their duties necessarily come across so many matters, but all these matters cannot be considered trade secrets or confidential matters or formulae, the divulging of which may be injurious to the employer, and if an employee, in the course of employment, has acquired some business acumen or ways of dealing with the customers or clients, the same do not constitute trade secret or confidential information, the divulging or use of which should be prohibited.

In the case of Ozone Spa Private Limited vs. Pure Fitness and Ors., MANU/DE/2182/2015 a Single Bench of the Delhi High Court held that “Defendants could not resile back after expressly agreeing to become a licensee/franchisee under Management Agreement which was in continuation of Franchise Agreement and said business agreed to fall within ambit of franchised business. Ingredients of tort of the passing off were satisfied. Plaintiff had goodwill in business of fitness center, spa and salon services which had been generated from business done by Plaintiff prior to that of Defendants. Defendants being franchisee and licensee of all these businesses under mark OZONE could not dispute the said position seriously being beneficiary under contract.”

Case of misrepresentation and resultant damage was glaring in the above case which could be seen in the conduct of Defendants which was completely mala fide and aimed at encashing upon the goodwill of the Plaintiff’s business. They were found to be inducing customers by offering discount coupons, associating Plaintiff OZONE spa with Hairmaster Salons, by having common staff roaming around the fitness center and providing salon services, etc., so as to cause confusion and deception amongst customers and to encash upon the Plaintiff’s established and captive customer base and cause damage to the Plaintiff’s goodwill acquired in respect of Salon services. Defendants have promoted their Hair Master Salon by riding upon the goodwill and reputation of the OZONE brand. Prima facie, it appeared that Defendants had been trying in a clandestine and surreptitious manner to filch Plaintiff’s clientele and tarnish their goodwill by diverting their business to their own competing business viz. Hair Masters/Hairmasters.

In the Ozone case cited above, the Court was also of the view that “it is well settled principle of law that the negative covenants contained in the agreement which are aimed at to operate during the subsistence/validity of the agreement in a commercial contract can be validly enforced and injunction for enforcement of the said covenant cannot be refused on the ground that the same are in restraint of the trade as the underlying purpose of the said negative covenant prohibiting the party to conduct the competing business is to serve the contractual relationship and there exists no such restraint of trade in such a case as the party so restricted is already doing the business as per commercial arrangement under the contract.”

Even when there was no specific contract with a confidentiality clause, the Delhi High Court in the case of John Richard Brady v. Chemical Process Equipments Private Limited, AIR 1987 Delhi 372, relying on Lord Denning, M. R. in Seager v. Copydex Limited 1967 RFC 349, held that “the law on this subject does not depend on any implied contract. It depends on the broad principles of equity that he who has received information in confidence shall not take unfair advantage of it.” It was also reiterated that the possessor of such information must be placed under a special disability in the field of competition in order to ensure that he does not get an unfair start. The High Court while granting an interim stay found it to be in the interest of justice to restrain the Defendants from abusing the know-how, specifications, drawings and other technical information regarding the Plaintiff’s machine “which was entrusted to them under express condition of strict confidentiality, which they have apparently used as a ‘spring-board’ to jump into the business field to the detriment of the Plaintiffs.”

CONCLUSION

It has therefore become imperative, in today’s cut-throat competitive culture, for organizations to keep a tight check over its IP rights so as to maintain their edge in the marketplace. Thus, it is concurrently crucial to have specific contracts in place, catering to different legions of persons/stakeholders and circumstances, in order to protect their confidential information, including amongst an organization’s allies, affiliates and employees. However, it is also important to distinguish what will be construed as amounting to confidential information and trade secrets, and will accordingly be granted protection from infringement by the Courts.

1 Parle Products Private Limited v. Parle Agro Private Limited, Bombay High Court in Notice Of Motion No. 4431 Of 2007 In Suit No. 3203 Of 2007

Under the Section 63 of Copyright Act, Cognizance of Offences

By Priya Adlakha, Tanvi Bhatnagar and Rima Majumdar

Copyright is an aspect of intellectual property which has assumed great importance in this modern day and age, as the advent of the internet and ease of electronic communication has made protection of copyrighted works and enforcement of rights more challenging than ever before. The global economy is dependent on the creation and distribution of intellectual property (IP), be it copyrights, patents, designs or trade marks. It is not a stretch to say that Intellectual Property shapes the world and our perception thereof in many ways. While the value and worth of intellectual property has indeed skyrocketed over the years, so has the resultant issues with respect thereto. Specifically, infringement of one’s IP has always been a constant part of this, resulting in significant loss to authors, inventors, creators, owners and businesses, and deception and financial disadvantage to the consumer. It is because of these reasons, the legislature has made the acts of infringement of IP rights to be an offence and provided for statutory penalties and imprisonment in addition to being a civil wrong, thus emphasizing upon the importance of copyright.

Often, IP owners have to take a conscious decision whether to opt for a civil or criminal action, or both, against infringers, in order to see the deterrent impact upon the infringer and his racket/channels. IP owners have several questions to be asked about the procedure of a criminal action including – Whether the Police will even register the FIR or not at the instance of complainant? Whether the Police will conduct a surprise search and seizure at the infringer’s premises? Whether the accused will be arrested by the Police or not? Whether the IP owner will be able to compound the offence later, once the matter is settled amicably? All these questions can be answered by looking into the specific Act/law governing the offence.

However, before one ventures into looking at the deterrent impact of criminal prosecution for any offence, let us briefly look at the three classification of offences.

THREE ASPECTS OF ANY CRIMINAL OFFENCEAs per prevalent criminal law in India, offences are covered under the following three heads:

- Cognizable and non-cognizable:

A cognizable offence is an offence wherein, the police can commence investigating the matter without taking prior permission from a Court, and arrests can also be made without a warrant. On the other hand, non-cognizable offences require the police to first seek permission from the Magistrate’s Court to commence investigation of the same, and the police is under no obligation to register a FIR on receiving any complaint alleging offences that are non-cognizable in nature.

Generally, offences that are grave in nature, for example murder, kidnaping, etc. are cognizable. The First Schedule of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), 1973, in Part I provides classification of all offences under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that are either cognizable or non-cognizable in nature. Part II of the First Schedule provides classification of offences against other laws, on the basis of the punishment prescribed under the said Acts, as under:

Category 1: If punishable with death, imprisonment for life or for more than seven years; cognizable and non-bailable; triable by Court of Session.

Category 2: If punishable with imprisonment for three years and above but not more than seven years; cognizable and non-bailable; triable by magistrate of the first class.

Category 3: If punishable with imprisonment: less than three years or a fine; non-cognizable and bailable; triable by any magistrate.

- Bailable and non-bailable:

A bailable offence is an offence in which, the arrested person can obtain bail as a matter of right. Whereas, non-bailable are those offences wherein, the decision to release a person on bail is made by the Courts, based on the facts and circumstances of the case. While adjudicating upon the issue of granting bail to an individual charged with a non-bailable offence, Courts take certain important factors in consideration, including but not limited to – whether the accused is a flight risk; risk of tampering of evidence by the accused once released on bail; whether the prosecution’s witnesses would be under any threat from the accused, etc.

Usually, offences that are cognizable in nature are in turn non-bailable. The First Schedule of Cr. P.C provides classification whether an offence is bailable or not.

- Compoundable and non-compoundable:

The third aspect of a criminal offence is whether it is compoundable or not. Section 320 of the Cr.P.C provides a list of offences as mentioned in the Indian Penal Code that may be compounded. Sub-section (9) of Section 320 provides that any offence (under IPC) that is not covered under Section 320, is by definition not compoundable.

When an offence is compoundable, it means that the complainant can enter into a compromise with the accused, and have the matter settled in Court. Sub-section (6) of Section 320 provides that the High Court or the Court of Sessions under Section 401 of Cr.P.C, may allow any person to compound an offence which such person is competent to compound.

On the other hand, non-compoundable offences are those that cannot be settled through a compromise between the parties, mainly due to the gravity of the offence. However, the High Court has ample power under Section 482 of Cr.P.C to quash an FIR and the subsequent proceedings thereto, for offences that are non-compoundable in nature, provided that the Court is of the view that if the criminal proceedings continue it will only be a waste of judicial time and because there is hardly any chance of success of the prosecution1.

The scope of this article is limited to discuss the controversy around the offence under Section 63 of the Copyright Act, 1957.

OFFENCE UNDER SECTION 63 OF THE COPYRIGHT ACT, 1957

Section 63 provides that any person who knowingly infringes or abets the infringement of a copyright that exists in any work, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months but which may extend to three years and with a fine, which shall not be less than fifty thousand rupees but which may extend to two lakh rupees.

It is however, pertinent to point out that when it comes to understand the power of Police to register a FIR and arrest the accused for an offence under Section 63, the Copyright Act itself is silent as to whether the offence under this Section is cognizable or not. Therefore, the issue went for consideration before various High Courts of the country at different point of times, which have given varied views and decisions on this rather glaring omission.

JUDICIAL PRONOUNCEMENTS ON COGNIZANCE OF OFFENCES VIS-À-VIS SECTION 63 OF COPYRIGHT ACT

In 2002, while deciding an application for anticipatory bail for offences under Section 63 of the Act, a single bench of the Hon’ble Gauhati High Court in the case of Jitendra Prasad Singh V. State of Assam (2003) 26 PTC 486 GAU, held that the expression “punishable with imprisonment for a term, which may extend to three years”, will mean that the imprisonment can be for a term as long as three years, but the expression, “punishable with imprisonment for less than three years” will mean that the offence is punishable with imprisonment for a period, which is less than three years.” Therefore, offences under Section 63 of the Act are non-bailable in nature, and as such an application for anticipatory bail will be maintainable.

The interpretation of the above judgement would be that the offence u/s 63 of the Copyright Act, would fall under Schedule 1 Part II Entry II, therefore, it would be cognizable and non-bailable.

In 2006, a similar situation arose before the Hon’ble Andhra Pradesh High Court in the case of Amarnath Vyas v State of Andhra Pradesh (2007) Cri LJ 2025 AP, wherein the Court had earlier rejected the anticipatory bail application of the accused u/s 438 Cr.P.C on the ground that the offence is bailable. Later, the Public Prosecutor for the state sought reconsideration of the previous order on the premise that the offence under Section 63 is not a bailable one. The learned Single Judge took a contrary view and held that “It is trite that the penal provisions shall have to be construed strictly. True there may be certain other class of offences which may fall in between classification II and classification III of Second Part of Schedule-I. Merely because they are not coming squarely within the domain of classification- Ill, they, cannot automatically be treated as included in the classification-II.”. “The expression ‘imprisonment for a term which may extend upto three years’, in my considered view, would not come squarely within the expression ‘imprisonment for three years and upwards’. Therefore, the offence punishable under Section 63 of the Act cannot be considered as a non-bailable one.”

Speaking on whether offences under Section 63 are cognizable or not, a Single Judge of the Kerala High Court in cases titled as Sureshkumar S/o Kumaran V. the Sub Inspector of Police 2007 3 KLT 36 and Abdul Sathar vs. Nodal Officer Anti-Piracy Cell AIR 2007 Ker 212, while hearing two writ petitions under Article 226 & 227 of the Constitution, held that since Section 63 of the Act is punishable with imprisonment for a period of 3 years, there can be no doubt that this falls under category 2 of Part II of the First Schedule of CRPC, and is consequently cognizable.

In 2013, Hon’ble Ms. Justice Gita Mittal of the Delhi High Court in the case of State vs. Naresh Kumar Garg CRL. M.C 3488/2012, relied upon the judgment of Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Avinash Bhosale v. Union of India (2007) 14 SCC 325, wherein the Supreme Court had observed that an offence punishable under Section 135(1)(ii) of the Customs Act, 1962 (Act of 1962) would be bailable since it is punishable with imprisonment for a term ‘which may extend to three years or fine or with both’. The Delhi High Court was of the view that since the punishment mentioned in both these sections is identical, therefore they can be read in consonance. The learned Single Judge also relied upon Amarnath Vyas (supra) of the Andhra Pradesh High Court.

The Single Judge of Rajasthan High Court in Pintu Dey vs. State of Rajasthan 2015(3) Cr. L.R. (Raj.) 1291, relying upon Amarnath Vyas (Supra) held that the offences under Sections 63 & 68A of the Copyright Act being punishable by sentence of imprisonment upto three years, are non-cognizable offences.

In 2019, Hon’ble Mr. Justice Vibhu Bhakru of the Delhi High Court, while hearing a quashing petition in the case of Anuragh Sanghi vs. State & Ors. in W.P.(CRL) 3422/2018 & CRL.M.A. 35858/2018, relying upon the judgements passed in Avinash Bhosale (Supra) and Naresh Kumar Garg (Supra) held that the offence under Section 63 of the Copyright Act is not a cognizable offence and quashed the FIR. Recently, in February 2021, a reference was made to the division bench of the Hon’ble Rajasthan High Court, Jodhpur Bench in the case of Nathu Ram vs. State of Rajasthan D.B. Crl. Ref. No. 1/2020 to answer the exact question of law “What would be the nature of an offence (whether cognizable or non-cognizable) for which imprisonment “may extend to three years” is provided and no stipulation is made in the statute regarding it being cognizable/non-cognizable.” The Division Bench considering all the aforesaid judgements and various other judgements passed by the Hon’ble High Courts and Supreme Court and applying the rule of ‘ex visceribus actus’ answered the reference as “that unless otherwise provided under the relevant statute, the offences under the laws other than IPC punishable with imprisonment to the extent of three years, shall fall within the classification II of offences classified under Part II of First Schedule and thus, shall be cognizable and non-bailable.” It has been held that the Single Bench Judgment of Rajasthan High Court in Pintu Dey (Supra), does not lay the correct law.

The reasoning given by the Hon’ble Division Bench of the Rajasthan High Court, Jodhpur Bench in the case of Nathu Ram (supra), appears to be the most appropriate one. The reliance placed by the Single bench of the Delhi High Court in the decision of the Hon’ble Supreme Court passed in Avinash Bhosale (Supra) which is in the context of an offence under the Customs Act, was not appropriate. The High Courts have not considered the intention of the legislature behind making certain acts of IP infringement as criminal offence and increasing the quantum of punishment as well as statutory penalties by way of amendments. It is pertinent to point out here that Section 103 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, which is another legislation for IP protection and enacted (after repealing The Trade & Merchandise Marks Act, 1958) much after the Copyright Act, 1957 (amended in 1984), makes the offence under Section 103 of the Trade Marks Act ‘a cognizable offence’.

A specific provision was added in the new Act i.e. Section 115 (3) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 which provides “that the offences under section 103 or section 104 or section 105 shall be cognizable.”

The wordings of Section 103 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 with Section 63 of the Copyright Act, 1957 as well as the quantum of punishment and penalty is similar, and the same is reproduced as below:

| Trade Marks Act, 1999 | Copyright Act, 1957 |

| Section 103. Penalty for applying false trade marks, trade descriptions, etc.—Any person who— (a) falsifies any trade mark; or (b) falsely applies to goods or services any trade mark; or (c) makes, disposes of, or has in his possession, any die, block, machine, plate or other instrument for the purpose of falsifying or of being used for falsifying, a trade mark; or (d) applies any false trade description to goods or services; or (e) applies to any goods to which an indication of the country or place in which they were made or produced or the name and address of the manufacturer or person for whom the goods are manufactured is required to be applied under section 139, a false indication of such country, place, name or address; or (f) tampers with, alters or effaces an indication of origin which has been applied to any goods to which it is required to be applied under section 139; or (g) causes any of the things above mentioned in this section to be done, shall, unless he proves that he acted, without intent to defraud, be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months but which may extend to three years and with fine which shall not be less than fifty thousand rupees but which may extend to two lakh rupees: Provided that the court may, for adequate and special reasons to be mentioned in the judgment,

impose a sentence of imprisonment for a term of less than six months or a fine of less than fifty thousand. |

Section 63. Offences of infringement of copyright or other rights conferred by this Act.—Any person who knowingly infringes or abets the infringement of— (a) the copyright in a work, or (b) any other right conferred by this Act [except the right conferred by section 53A], [shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than six months but which may extend to three years and with fine which shall not be less than fifty thousand rupees but which may extend to two lakh rupees]: Provided that [where the infringement has not been made for gain in the course of trade or business] the court may, for adequate and special reasons to be mentioned in the judgment, impose a sentence of imprisonment for a term of less than six months or a fine of less than fifty thousand rupees.] |

Further, the power given to the Police under Section 64 of the Copyright Act, for conducting search and seizure at the infringer’s premises and produce the seized goods before the Magistrate, is actually rendered without teeth, unless the Police has the power to register the FIR and arrest the infringer without a warrant from the Magistrate at the place of offence.

Though the judgement passed by the Hon’ble Division Bench of the Rajasthan High Court in Nathu Ram (supra) could be persuasive upon all the High Court’s having bench of coordinate or less strength, the controversy needs to be authoritatively settled by the Hon’ble Supreme Court once and for all, or can be settled by suitable amendment in the Act, wherein a specific provision should be included to make the offence as ‘Cognizable’ to make it at par with the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

CAN OFFENCES UNDER SECTION 63 BE SETTLED THROUGH COMPROMISE?

Coming to the third aspect, whether an offence under Section 63 of the Copyright Act is compoundable or not, the Courts seem to be in unison about the same being non-compoundable in nature. However, the powers of the High Court under Section 482 Cr.P.C are ample and wide enough to allow the Court to quash the proceedings arising out of a non-compoundable offence as well. In the case of B.S. Joshi vs. State of Haryana, (2003) 4 SCC 675, the Hon’ble Supreme Court had held that “even though the provisions of Section 320 Cr.P.C would not apply to such offences which are not compoundable, it did not limit or affect the powers under Section 482 Cr.P.C., if for the purpose of meeting the ends of justice, quashing of FIR is necessary.”

In the case of Devender Bansal & Anr. vs. State (N.C.T. of Delhi) & Anr., Crl. M.C. 2059/2016, the Hon’ble Delhi High Court had held that “notwithstanding the fact that the offence under Section 63 of the Copyright Act is a non-compoundable offence, there should be no impediment in quashing the FIR under this section, if the Court is otherwise satisfied that the facts and circumstances of the case so warrant.” The parties in the present case had amicably settled their issues, and the Court quashed the FIR by referring to the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Gian Singh vs. State of Punjab, (2012) 10 SCC 303, wherein the Apex Court had recognized the need of amicable resolution of disputes in cases like the instant one.

In the case of Sanjay Kumar Behera & Ors. vs. State (N.C.T. of Delhi) & Anr. Crl. M.C. 10/2012 the Delhi High Court had quashed an FIR registered under Sections 52A/63/68A of the Copyright Act, since the parties had settled their disputes through a settlement agreement. It was pointed out by the Counsel for the State of NCT of Delhi that offences under Section 63 of the Copyright Act are non-compoundable in nature. However, since the complainant had resolved its issues with the accused, the court held that no useful purpose would be served in proceeding with the trial in this case, and proceeded to quash the FIR.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court in the case of Narinder Singh vs. State of Punjab, (2014) 6 SCC 466 had also held that those criminal cases that are having predominantly civil character, particularly those arising out of commercial transactions or arising out of matrimonial disputes/relationships, should be quashed when the parties have resolved their entire disputes among themselves.

We are of the view that this ratio of the Supreme Court will apply squarely on cases involving IP infringement, whether it is copyright, trade mark, patents etc. since the same are predominantly civil in nature.

[1] Sanjay Singh vs Govt. Of Nct Of Delhi & Anr., Delhi High Court, Crl. M.C. No. 538/2009

It’s worth it for you(your trade marks)!

By Lucy Rana and Ragini Ghosh

CASE ANALYSIS: L’ORÈAL S.A. v. ASHOK KUMAR & ORS. – CS (COMM) 474/2021

The well-known personal care and beauty brand – L’Orèal S.A., recently stumbled upon an entity who was found to be fraudulently impersonating them by using their trademarked brand name Loreal in their domain name while also using phony business email addresses suffixing their domain name. Upon discreetly demanding documents to ascertain a proof of validity of their business, under the disguise of setting a business deal in motion, L’Orèal was able to make the infringer furnish fake and forged documents, such as fake GST certificate, fake certificate of incorporation, forged cancelled cheques, etc., made out in the name of L’Orèal S.A. The infringer was also found to be operating a rogue website at the domain name www.lorealglobal.in.

L’Orèal S.A. (Plaintiff) lodged a commercial case in the Delhi High Court against the infringing party misusing the name of the Plaintiff’s well-known company for impersonation, and the domain name registrar and the telecom service provider were made parties as Defendants to the case.

Grounds

- That L’Orèal S.A. (Plaintiff) is an anonymously organized society, existing under the laws of France, and are actively engaged in the business of manufacturing, distributing and sale of personal care and beauty products;

- That the trademark ‘L’ORÈAL’ has been adopted and used by the Plaintiff since the year 1900, along with various stylized labels thereof;

- That owing to their operations, they have acquired goodwill and reputation both globally as well as in India, and hold several trademark registrations in India as well;

- That the Defendant is impersonating the Plaintiff, L’Orèal A.’s, Indian subsidiary;

- That the Defendants are hosting a rogue website under the domain name lorealglobal.in, which is deceptively similar/identical to the Plaintiff’s original website; and are also impersonating as an employee of the Plaintiff company and using email IDs that incorporate the Plaintiff’s trademark/domain name, such as operations@lorealglobal.in, paresh.deshmukh@lorealglobal.in and ashwini.r@lorealglobal.in.

- That along with the aforementioned email IDs, the Defendant is also operating a mobile number linked to the said email IDs;

- That in view of the abovementioned contentions, the Plaintiff has established a prima facie case to seek an injunction against the actions of the Defendant.

Accordingly, Judge Sanjeev Narula observed that the balance of convenience lies in favour of the Plaintiff and ex parte directed the following:

- Defendant No. 1 (unknown) and its proprietors/partners, agents, representatives, distributors, assignees, heirs, successors, stockists and all others acting for and on their behalf are restrained from using the website lorealglobal.in and email addresses – operations@lorealglobal.in, paresh.deshmukh@lorealglobal.in and ashwini.r@lorealglobal.in, and/or any other email address, website, social media accounts containing the Plaintiff’s trade mark;

- Defendant No. 1 is further also restrained from using the Plaintiff’s trade-name by any other mode or manner, including the Plaintiff’s trade-mark/label ‘L’OREAL’ and/or other formative trademarks/labels/variants in relation to any impugned, fraudulent and violative activities amounting to or likely to amount to

- Infringement;

- Passing-off;

- Violation of the Plaintiff’s proprietary rights in their trade name including the copyrights of the Plaintiff; and

- Falsification, unfair and unethical trade practices in respect of Plaintiff’s aforesaid registered trademark ‘L’ORÈAL’.

- Defendant No. 2 (Domain name registrar) are directed to furnish all details and information about Defendant No. 1 to the Plaintiff, including payment details (as provided while purchasing the impugned domain name), and to block access to the impugned domain name/website at– lorealglobal.in.

- Defendant No. 3 (telecom service provider) is directed to disclose to the Plaintiff, the user details along with KYC details of the mobile number found to be used by Defendant No. 1.

- Defendant Nos. 4 and 5 are directed to issue directions to all internet service providers registered under it to block access to the impugned domain name/website – lorealglobal.in.

- The Delhi Police is directed to submit a report in respect of the Plaintiff before the Delhi High Court.

The matter has been listed once again before the Delhi High Court on December 08, 2021.

In the instant matter, the interim order passed by the Delhi High Court shows its pro-active approach in effectively redressing a case, even though the whereabouts of the infringer of the Plaintiff’s trademark was yet to be ascertained. The order was delivered effectively, providing ample scope to practically ascertain the details of the infringer by directing the Domain Name Registrar and the Telecom Service Provider to furnish the same. Further, to ensure that the infringers are in fact restrained from operating the impugned website, the Court went the extra mile by issuing a direction to block public access on the impugned website as well. This evidenced how curbing further harm/loss to the injured party holds first priority in the eyes of the Court, and that they were therefore committed to tackling the matter without letting the lack of details about Defendant No. 1 act as an impediment in the substantial adjudication of the matter. Further, apart from granting the ex parte injunction to safeguard the Plaintiff’s interest, it may be pertinent to note that the directions issued innately also safeguarded the interests of the consumers, wherein the existence of a fake domain name operating under the identical trade mark of the Plaintiff, posed a grave and inherent threat to the target consumers as well. Therefore, the injunction also acts to efficiently mitigate the same, as the instance of infringement, i.e. the adoption of an identical domain name, may in fact quite likely be overlooked by any person/consumer of average intellect and memory.

Girishma Sai Chintalacheruvu, Associate at S.S. Rana & Co. has assisted in the research of this article.

The Panorama Freedom

By Rupin Chopra and Nitika Sinha

Freedom of panorama, an exception to copyright law, refers to the legal right to publish pictures of artworks which are in a public space. The name takes its roots from the German term Panoramafreiheit meaning ‘panorama freedom’. These laws generally limit the right of the copyright owner to take action for breach of copyright against the infringer.

Roughly every country has some sort of freedom of panorama. However, some countries have more strict interpretations than others. This article seeks to provide a short history of the right, provide the major considerations to be taken into account when taking a picture in public, and consequently compare the law on the subject across various jurisdictions.

History

Post the invention and relative cheapening prices of cameras, concerns rose regarding the privacy of people on streets. In France, one of the first laws curtailing freedom of panorama arose, albeit from a privacy perspective. Similarly, in Italy, similar laws were enacted, however for the protection of cultural heritage. However, these were negative laws, prior to the existence of a ‘freedom’ itself.

Germany was the birthplace of the right itself. In 1837, the German Confederation enacted a new common standard on copyright law. Independent states within the Confederation brought forth their concerns, and in 1840, the Kingdom of Bavaria enacted one of the first ‘freedom of panorama’ in the world, providing an exception to the copyright law with respect to any “works of art and architecture in the exterior contours”.i Slowly, this right extended to the entirety of Germany, and further lent to the world.

Major Considerations

Public Space

What constitutes a public space or public domain may be different across jurisdictions. This is relevant not only for ‘what’ can be reproduced, but also for ‘where’ something can be reproduced. For example, in Germany, reproductions of a work cannot be taken from a place of privacy. Hence, while there exists a freedom of panorama in Germany, taking pictures from the balcony of your home of a copyrighted building would not be allowed.

In some places, a public space may refer to only outdoor spaces, such as parks or streets. Whereas, in other jurisdictions, it may also cover indoor spaces such as public museums, public libraries, etc.

Purpose

The other major concern that differentiates the law between jurisdictions is whether the reproduction of the work is being done for a commercial use or for a non-commercial use. Countries including France, Belgium and Germany do not generally allow freedom of panorama for commercial use. Some jurisdictions, such as Iceland allow reproduction only for educational purposes, and may allow for cinematographic purposes if such reproduction is incidental.

Artistic Works

The final consideration to be kept in mind is of artistic works such as sculptures, paintings or murals placed in public space. Usually, there exist restrictions on reproduction of such artistic works, as courts believe that such rights should be reserved with the authors of the work itself.

Comparative Analysis across Jurisdictions

India

In India, this is largely covered under Section 52 to the Copyright Act, 1957. Summarily, making or publishing of paintings, drawings, engravings, photographs or inclusion in cinematographic films of any works of architectures, or any artistic work that is situated in a public place does not constitute infringement of copyright.

The relevant provision, Section 52(s) – (u) of the Copyright Act, 1957, states –

“52. Certain acts not to be infringement of copyright — (1) The following acts shall not constitute an infringement of copyright, namely,—

(s) the making or publishing of a painting, drawing, engraving or photograph of a work of architecture or the display of a work of architecture;

(t) the making or publishing of a painting, drawing, engraving or photograph of a sculpture, or other artistic work falling under sub-clause (iii) of clause (c) of section 2, if such work is permanently situate in a public place or any premises to which the public has access;

(u) the inclusion in a cinematograph film of—

(i) any artistic work permanently situate in a public place or any premises to which the public has access; or

(ii) any other artistic work, if such inclusion is only by way of background or is otherwise incidental to the principal matters represented in the film;”

Under section 2(c) of the same act, artistic works include works of architecture. Hence, there exists an exception on taking such images and videos. This exception is not subject to any qualifiers of non-commercial use either.

While there exists freedom of panorama for artistic works as well under Section 52(t), this does not mean that this exception can be extended to copies of an original work situated in a public place. In the case of The Daily Calendar Supplying vs The United Concern,ii the Madras High Court held that where multiple poster copies of an oil painting were sold by an artist and placed in public places, does not imply that these can be reproduced freely.

In very limited instances, buildings’ designed may also be trademarked (such as the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, Mumbai). In such instances, the trademark registration and the class of trademark would also govern its reproduction.

Tabular Analysis

The following table summarises the laws across various jurisdictions –

| Country | Freedom of Panorama | For Commercial Purposes | Of Artistic Works | Special Laws |

| Indiaiii | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Australiaiv | ✔ | ✔ | ❌ | Artistic works may not be reproduced if they are placed temporarily |

| Belgiumv | ✔ | ❌ | ✔ | Reproduction must not affect the normal exploitation of the work or unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author |

| Brazilvi | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Canadavii | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Chinaviii | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | The name and title of the work shall be mentioned |

| Congoix | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | Reproduction may only be done for educational purposes, or for cinematography, if such reproduction is incidental |

| Denmarkx | ✔ | ❌ | ✔ | |

| Francexi | ✔ | ❌ | ❌ | Reproduction is allowed if copyrighted material is incidental or accessory to the reproduction |

| Germanyxii | ✔ | ❌ | ❌ | Reproduction must take place from a public place |

| Hong Kongxiii | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Hungaryxiv | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Icelandxv | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | Reproduction may only be done for educational purposes, or for cinematography, if such reproduction is incidental |

| Indonesiaxvi | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | No explicit legislation |

| Israelxvii | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Italyxviii | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | |

| Japanxix | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Artistic works cannot be reproduced for commercial purposes |

| Malaysiaxx | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Mexicoxxi | ✔ | ❌ | ✔ | Reproduction must not affect the normal exploitation of the work or unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author |

| Moroccoxxii | ✔ | ❌ | ❌ | Reproduction is allowed if copyrighted material is incidental or accessory to the reproduction |

| New Zealandxxiii | ✔ | ❌ | ❌ | |

| Nigeriaxxiv | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Philippinesxxv | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | While there is no freedom of panorama per se in the Philippines, there exists an exception ‘as part of reports of current events. A bill for freedom of panorama is proposed but pending. |

| Polandxxvi | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Romaniaxxvii | ✔ | ❌ | ✔ | |

| Singaporexxviii | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |