By Lucy Rana and Huda Jafri

Introduction

Comparative advertising is an accepted, even welcome, commercial practice. It encourages competition, informs consumers, and helps brands differentiate themselves. However, the legal boundary is well-settled: an advertiser may laud its own product, but cannot disparage competing products, particularly through misleading or accusatory statements.

The Hon’ble Delhi High Court’s 2025 ruling against Patanjali on its “Dhoka Chyawanprash” advertisement in Dabur India Limited Vs. Patanjali Ayurved Limited & Anr.[1] revisits and reinforces this boundary. By categorically rejecting Patanjali’s defence of puffery and commercial free speech, the Court clarified that speech becomes unlawful when it crosses into deception, denigration, or harm to competitors.

This case is especially significant for the FMCG and Ayurvedic sectors, where celebrity-endorsed claims, health-related assertions, and consumer trust play central roles.

Background of the Dispute

The present dispute arose from Patanjali’s advertisement in which a well-known public figure “Baba Ramdev” suggested that mainstream chyawanprash[2] brands were “dhoka” (deceit of deception in English). Although no company was named.

Dabur, established in 1884, commands over 61% of the chyawanprash market and manufactures strictly in accordance with classical Ayurvedic texts listed under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. The company recorded a turnover of ₹125,630 million (₹12,563 crore) in FY 2024–25.[3]

Patanjali, founded by Baba Ramdev and Acharya Balkrishna, is a powerful competitor with wide public influence built on yoga, Ayurveda, and personality-driven endorsements. The brand often uses bold comparative messaging and markets its product as “Patanjali Special Chyawanprash — 51 Herbs. 1 Truth.”

The Impugned Advertisement

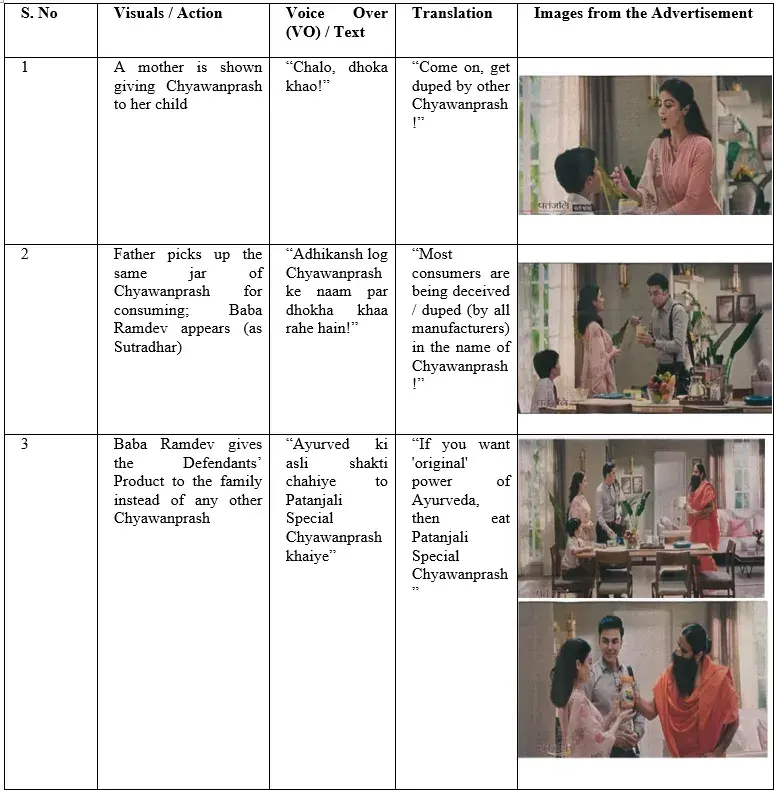

The advertisement at the centre of the dispute aired on Star Plus and across digital platforms in October 2025. It contained several scenes and dialogues that the Court reproduced in its order. Offending screenshots from the Impugned Advertisement are as under:

Dabur’s Case: Why This Was Not Mere Puffery?

Dabur India Limited advanced a carefully structured and legally compelling case, asserting that Patanjali Ayurved’s chyawanprash advertisement crossed well-established boundaries of permissible comparative advertising and entered the realm of generic disparagement, false factual assertion, and commercial defamation.

Dabur emphasized that Patanjali’s use of the term “dhoka”, which unmistakably signifies fraud, cheating, or deception, was not a humorous exaggeration or an instance of subjective puffery. Instead, it was a direct allegation of dishonesty against every chyawanprash manufacturer in the market except Patanjali itself.

Importantly, the advertisement did not merely claim that Patanjali’s chyawanprash was “better,” “stronger,” or “more effective.” Rather, its central message was that all other chyawanprash products were fundamentally deceptive, a claim far beyond the legally permissible limits of comparative messaging.

To reinforce its position, Dabur relied on several substantive grounds:

- Statutory Compliance and Ayurvedic Authenticity

Dabur argued that chyawanprash is a regulated product, manufactured strictly as per formulations prescribed in classical Ayurvedic treatises listed in the First Schedule of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940.Every licensed manufacturer, including Dabur, must comply with:- Textually authentic Ayurvedic compositions such as Charaka Samhita, Rasa Tantra Saar, and Shaarangdhar Samhita.

- Mandatory AYUSH licensing requirements.

- Ingredient disclosures and quality standards mandated by law.

Thus, suggesting, directly or indirectly, that licensed chyawanprash manufacturers were deceiving the public was not only false but statutorily impossible. Dabur contended that Patanjali’s advertisement misled consumers about the legal and scientific foundations of Ayurvedic formulations and cast unwarranted aspersions on the entire category of compliant manufacturers.

- Market Leadership and the Consequence of Generic Disparagement

Dabur holds over 61% market share in the chyawanprash segment. Under Indian law, when an advertiser disparages an entire product category, the market leader suffers the most significant reputational damage.The Court in numerous cases, including Dabur v. Emami[4] (2004) and Colgate v. Anchor Health[5] (2003), has held that:- Generic disparagement occurs when a product class is condemned.

- A plaintiff can be harmed even if unnamed.

- Harm intensifies when the plaintiff dominates the category being disparaged.

Dabur therefore argued that Patanjali’s statements, which equated all chyawanprash sold in India (except its own) with “fraud,” necessarily fell upon Dabur as the principal and most identifiable representative of the product class.

- Misuse of Authority and Influence of Baba Ramdev

Dabur highlighted that Baba Ramdev, who appears prominently in the commercial, is perceived by the Indian public as:- A yoga guru,

- A promoter of Ayurveda, and

- An authoritative figure on health, wellness, and natural remedies.

His statements carry elevated persuasive authority. The advertisement leveraged this credibility to convey an impression that his pronouncements were rooted in authentic Ayurvedic expertise.

This heightened the likelihood that consumers would:

- Accept his criticisms as factual,

- Doubt the efficacy of competing brands, and

- Avoid other chyawanprash products entirely.

Thus, Dabur argued that the advertisement did not simply promote Patanjali’s own product, it weaponised celebrity authority to delegitimise the entire chyawanprash category.

- Violation of Prior Judicial Directions

Dabur also pointed out that Patanjali had previously been cautioned by a Division Bench of the Delhi High Court, which had permitted Patanjali to describe competing products as “ordinary” but had categorically restrained it from:- Denigrating competitors,

- Portraying them as harmful, deceptive or fake,

- Suggesting that only Patanjali’s product was authentic.

Despite this judicial warning, Patanjali escalated its tone from “ordinary chyawanprash” to “dhoka chiwanprash,” violating both the letter and spirit of the earlier order.

- Beyond Puffery: The Threshold of Actionable Disparagement

Dabur argued that Patanjali’s statements were not subjective claims such as:- “Our chyawanprash tastes better,”

- “Ours contains more herbs,” or

- “Ours is more effective.”

Instead, Patanjali’s claim was a factual assertion that:

- All other chyawanprash are deceptive,

- Consumers are being cheated,

- Only Patanjali offers real Ayurvedic power.

This crosses the line into:

- Actionable disparagement,

- Commercial defamation, and

- Misrepresentation under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019.

Dabur therefore asserted that the commercial must be restrained in the interest of fair competition, truthful advertising, and public confidence in regulated Ayurvedic products.

Patanjali’s Defence: The Attempt to Recast “Dhoka”

Patanjali attempted to defend the commercial on multiple fronts, but each defence was found legally unsustainable.

- “Dhoka” as Slang or Hyperbole

Patanjali argued that the word “dhoka” was used colloquially to signify “ordinary,” “inferior,” or “less potent,” not “fraud.”According to them, Indian consumers:- Understand such expressions as playful exaggerations,

- Do not interpret them literally,

- And therefore do not perceive them as accusations of criminal deception.

However, the Court noted that Patanjali did not show any evidence, survey-based or linguistic, that “dhoka” is understood even informally to mean “ordinary.”

- No Direct Reference to Dabur

Patanjali contended that since Dabur was not shown, named, or referred to, the plaintiff lacked a cause of action.This defence relied on the premise that:- Comparative ads must target a specific product to be actionable,

- Generic claims cannot injure an unnamed competitor.

However, Indian jurisprudence directly contradicts this. Courts have consistently held that indirect disparagement is sufficient, especially when the plaintiff is the market leader.

- Reliance on Article 19(1)(a)Patanjali argued that the advertisement was protected under the constitutional right to free speech. It cited Tata Press Ltd. v. MTNL[6], where the Supreme Court recognized commercial advertising as a legitimate expression.But this argument ignored a critical nuance of that judgment, that misleading, unfair, or deceptive advertisements do not enjoy constitutional protection and may be regulated under Article 19(2).

- Consumer Perception and HumourPatanjali maintained that:

- Advertisements are often exaggerated,

- Consumers do not take them literally,

- And therefore the statement “dhoka” should not be interpreted as a factual claim.

However, the advertisement’s tone, visuals, and message conveyed a serious assertion, not humour. Unlike humorous comparative ads, this one featured a health guru solemnly warning consumers about “deception.”

The Hon’ble Court’s Reasoning: Why “Dhoka” Could Not Be Defended

Hon’ble Justice Tejas Karia’s order provides a nuanced interpretation of advertising standards, statutory context, and consumer psychology.

- “Dhoka” Means Fraud- Not Mere Exaggeration

To assess Patanjali’s linguistic defence, the Court examined dictionary texts and judicial interpretations. The term “dhoka” was found to carry meanings such as:- Fraud

- Betrayal

- Cheating

- Deception

The Court rejected Patanjali’s attempt to dilute the term, holding that:

- Consumers cannot be expected to reinterpret “dhoka” as harmless exaggeration,

- Advertisers cannot retrospectively redefine a term to escape liability,

- Use of such a word against a statutorily regulated product category is per se defamatory.

- A Clear Case of Generic Disparagement

The Court reaffirmed that even absent a specific reference to Dabur, the advertisement disparaged an entire class of products.Generic disparagement becomes particularly grave where:- The plaintiff dominates the category,

- The category is regulated by statutory norms,

- The advertisement presents itself as factual rather than satirical.

Thus, the commercial violated settled law on fair comparative advertising.

- Misleading Commercial Speech Is Not Constitutionally Protected

Hon’ble Justice Karia reiterated that:- Article 19(1)(a) protects truthful, informative, non-harmful commercial speech.

- It does not protect misleading or disparaging advertisements.

- Advertisers cannot invoke free speech to justify defamation or misrepresentation.

Thus, Patanjali’s constitutional defence failed at the threshold.

- Statutory Compliance of Competing Manufacturers

Since chyawanprash is manufactured exclusively as per classical Ayurvedic texts specified under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, suggesting that licensed manufacturers were deceiving the public was factually false.The Court noted that:- Products manufactured under statutory oversight cannot be dismissed as “fraud.”

- Patanjali’s claim was not hyperbole but a falsehood about regulated compliance.

- Heightened Influence of Celebrity Endorsement

Because Baba Ramdev is widely seen as an authority on Ayurveda,- His statements are perceived as expert pronouncements,

- Consumers are more likely to accept his views unquestioningly,

- The disparaging effect of his statements is amplified.

Thus, the harm caused by this advertisement was significant and immediate.

The Interim Injunction:

Hon’ble Court restrained Patanjali from:

- Airing or re-airing the impugned advertisement on television,

- Circulating it on digital platforms such as YouTube and Instagram,

- Disseminating it through print or online media,

- Using the term “dhoka” or any similar term to describe chyawanprash or its manufacturers.

The Court further ordered Patanjali to ensure the advertisement’s removal from all platforms within 72 hours, directing a comprehensive takedown from:

- Television channels

- YouTube

- Social media

- Patanjali’s own websites

- Third-party digital platforms

This sweeping interim injunction reflects the seriousness with which the Court viewed the violation.

Conclusion

The Hon’ble Delhi High Court’s injunction against the “dhoka chyawanprash” advertisement is more than a reprimand to one brand; it is a reaffirmation of the ethical bedrock on which India’s advertising ecosystem must rest.

In an industry where creativity often pushes boundaries, this case draws a bright, non-negotiable line: advertising may persuade, but it may not deceive; it may elevate one product, but it may not malign others without factual basis.

By prohibiting Patanjali from branding an entire product category as “dhoka,” the Court has protected not just Dabur’s goodwill, but the integrity of competitive markets and the trust of consumers.

The judgment stands as a vital marker in Indian commercial jurisprudence, grounded in fairness, vigilance, and the principle that truth in advertising is non-negotiable.

[1] CS(COMM) 1182/2025M

[2] A blend of herbs and spices, widely consumed in India as an immunity booster or dietary supplement.

[3] CS(COMM) 1182/2025

[4] Dabur India Limited v. Emami Limited, 2004 SCC OnLine Del 431

[5] Dabur India Limited v. Colgate Palmolive, CS(COMM) 1182/2025

[6] Tata Press Ltd. v. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd., (1995) 5 SCC 139,