Increase in amount of Individual Fee to be paid for Singapore to WIPO- w.e.f. 26 May, 2022

Delhi High Court notifies New Roster – New Addition in the IPD Division

Non-Conventional Trademarks in India

Lost in the crowd! – The life of generic trademarks

Increase in amount of Individual Fee to be paid for Singapore to WIPO- w.e.f. May 26, 2022

By Arpit Kalra

The Madrid Protocol is a convenient and cost-effective system that offers the owner of the trademark the possibility to have their trademark protected in several countries (up to 120 countries*) by filing only one application and submitting respective set of fees for each country to be designated. The System allows central management of trademark registrations with effects in various countries by providing a user-friendly, expeditious and cost-effective set of procedures for the central filing of trademark applications.

The Government of Singapore has recently notified to the Director General of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a declaration regarding slight hike (as under) with respect to the fee payable while choosing Singapore in an International Application:

| Items | Amount

(in Swiss francs i.e. CHF) |

|

| Until May 07, 2022 | To be applicable with effect from May 26, 2022 | |

| Application or Subsequent Designation for each class of goods or services | 242 | 261 |

| Renewal | 270 | 302 |

Taking view of the abovementioned notification, with effect from May 26, 2022, the aforesaid increase in the fee shall come into force in the following scenarios:

- When designating Singapore in an international application which is filed on or after May 26, 2022

- When designating Singapore subsequently in an international application which is received on or after May 26, 2022

- When Singapore has been designated in an international registration which is renewed on or after May 26, 2022

Therefore, it is recommended that all the Brand Owners who are looking to apply for their mark / brand in Singapore through WIPO via Madrid Protocol should take appropriate steps before May 26, 2022 in order to avoid the hike in the amount of the Individual Fee to be paid for Singapore to WIPO.

Related Posts

Iraq joins the PCT System- WIPO

Delhi High Court notifies the New Roster – New Addition in the IPD Division

By Priya Adlakha and Tanvi Bhatnagar

The abolition of the Intellectual Property Appellate Tribunal (IPAB) and transfer of the cases from the erstwhile IPAB to the respective High Courts, led to a lengthy debate regarding the fate of the pending cases with the IPAB and how High Courts which are already burdened with backlog, will effectively manage dealing with Intellectual Property cases.

In a First, Delhi High Court in order to solve the aforesaid conflict and to avoid multiplicity of proceedings and possibility of conflicting decisions with respect to same trademark, patents, designs etc established an Intellectual Property Division on July 6, 2021 (https://ssrana.in/articles/delhi-high-court-creation-intellectual-property-division-ipd/).

The Delhi High Court notified the ‘Delhi High Court Intellectual Property Rights Division Rules, 2022’ on February 24, 2022 and these rules govern all the IPR matters that are pending before the IPD of the Delhi High Court (rules can be accessed here https://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2022/233739.pdf).

On February 28, 2022, the Delhi High Court notified a Judges Roster, as per which, Hon’ble Ms. Justice Pratibha M. Singh and Hon’ble Ms. Jyoti Singh were nominated to function as the ‘IP Division’. The Hon’ble Judges were to hear the matters of the following categories:

| Hon’ble Ms. Pratibha M. Singh | a) Matters to be heard by the Commercial Division relating to IPR disputes;

b) Matters relating to Intellectual Property Rights; c) IPR suits upto the year 2018 and of the year 2022; d) Regular hearing matters of the above category. |

| Hon’ble Ms. Jyoti Singh | a) Matters to be heard by the Commercial Division relating to IPR disputes;

b) Matters relating to Intellectual Property Rights; c) IPR suits of the years 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022; d) Regular hearing matters of the above category. |

Since nine (9) new judges have been sworn in as judges of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court, the Court notified its new Judges Roster w.e.f. May 18, 2022. According to the new Roster, there has been an addition in the IPD, Hon’ble Mr. Navin Chawla, who was previously sitting in a Division Bench along with Hon’ble Mr. Justice Vipin Sanghi, is now a part of the IPD along with Hon’ble Ms. Pratibha M. Singh and Hon’ble Ms. Jyoti Singh.

All the three judges will be hearing the cases of the following categories:

| Hon’ble Ms. Pratibha M. Singh | a) Matters to be heard by the Commercial Division relating to IPR disputes;

b) Matters relating to Intellectual Property Rights; c) IPR Suits of the years 2020, 2021 and 2022; d) Regular hearing matters of the above category. |

| Hon’ble Mr. Justice Navin Chawla

|

a) Matters to be heard by the Commercial Division relating to IPR disputes;

b) Matters relating to Intellectual Property Rights; c) IPR Suits of the years 2019, 2020 and 2022; d) Regular hearing matters of the above category. |

| Hon’ble Ms. Jyoti Singh | a) Matters to be heard by the Commercial Division relating to IPR disputes;

b) Matters relating to Intellectual Property Rights; c) IPR Suits upto the year 2018 and of the years 2019 & 2022; d) Regular hearing matters of the above category. |

Further, as per the new Roster an appeal from any order or judgment of the IPD Division will go before the Division Bench compromising of Hon’ble Mr. Justice Vibhu Bakhru and Hon’ble Mr. Justice Amit Mahajan.

Related Posts

Delhi HC Invites Suggestions for Final Draft Rules Governing IPD and Patent Suits

DELHI HIGH COURT DIRECTS CREATION OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY DIVISION (IPD)

The Non-Conventional Trademarks in India

By Ananyaa Banerjee and Sandhya A. Parimala

Due to the advent of technology and accessibility of products with just a click of the button, there is a growing need for the protection of brands and their uniqueness. At this point, the importance of trademark protection is well understood by the brand owners. Protection of the various facets of brands becomes necessary to maintain the uniqueness and recall of the brand. Even from the customer’s point of view, trade mark protection is necessary as the same denotes the origin of that particular product and assures the customer of its quality.

The Trade Marks Act, 1999 defines “trade mark” as:

“a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include the shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours.[1]

Marks such as signs, icons, words, slogans or a mixture of them are traditionally seen as the subject matter of a trade mark application[2]. These are conventional trade marks which are expressly protected under the Act[3], and are understood as such by the consumers in general.

There is a separate category of marks that form an identity and instant connection with the brand by engaging the senses of smell, taste, sound, touch etc. These are known a non-conventional or non-traditional trade marks.

Importance of Non-Conventional Trademarks

Due to enormous increase in the availability of varied products and the limitless promotions carried out by the brand owners, there is an increase in the need to have a permanent mark or consumer memory. The primary aim behind any trade mark is to create an impact in the minds of the potential consumer which in turn creates a recall value of that brand. The packaging, advertisement storylines, brand narrative etc directly and instantly associate the particular product with the producer thereby establishing a connection of the consumers with the products/brand which goes way beyond just a name into a zone of brand value, recognition and loyalty. The need for a unique and distinctive identity is what has led to the growing use of unorthodox and non-conventional marks. Furthermore, with the wider reach of the internet and e-commerce, it is clear that non-conventional markings will attract the attention of users far more effectively than traditional markings. Such trade marks also play a vital role in aiding the visually / hearing impaired and uneducated people to identify the source/origin of the product using alternate indicators. However, despite having great importance, a very small number of non-conventional trade marks are being registered as compared to their traditional counterparts.

Is a Non-conventional trademark recognized under the Indian Trademark Law?

The Trade Marks Act, 1999 does not define the categories of marks registrable. The Act defines what marks are not registrable under two headings, namely; Absolute grounds of refusal[4] and Relative grounds for refusal[5] thus, laying the requisites for registration of a trade mark. The basic qualification for registrability of a mark is contained in the definition of trade mark itself, namely:

- Capable of being represented graphically, and

- Capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others.[6]

There is a requirement for all the trade marks to be able to be graphically represented, for the same to be eligible for registration. The 2017 Rules define graphical representation to mean representation of a trade mark for goods or services in paper form which also includes digitized form.[7] Therefore, to prove if a particular mark can be registered under the Indian Trade Mark Law, it is sufficient if the mark to be registered is or can be represented graphically and is capable of distinguishing the goods and services of that product from others. Due to the inclusive nature of the definition of a ‘trade mark’, any non-conventional trade mark can fit into the ambit of a trade mark if the above two conditions are satisfied. Therefore, the important question to be answered is if the non-conventional marks can be graphically represented and are distinctive of the products.

Types of Non-conventional trademarks

Colour marks: The Trade Marks Act, 1999 recognizes colour combination as trade mark.[8] Red Bull AG, which is a famous manufacturer of energy drinks, has registered the Abstract Blue Silver Colour ( ) in Class 32.[9] In other jurisdictions, colour marks have been specifically granted registration, thereby giving the proprietor exclusive rights over the single colour (eg, the colour purple for Cadbury’s Diary Milk chocolate). In India, the Trade Marks Manual recognizes the registration of a single colour trade mark and many entities have been successful in registering a single colour trade mark. For example, Victorinox AG registered a single colour mark (

) in Class 32.[9] In other jurisdictions, colour marks have been specifically granted registration, thereby giving the proprietor exclusive rights over the single colour (eg, the colour purple for Cadbury’s Diary Milk chocolate). In India, the Trade Marks Manual recognizes the registration of a single colour trade mark and many entities have been successful in registering a single colour trade mark. For example, Victorinox AG registered a single colour mark ( ) in Class 08[10]. Further, a single colour can also be protected by way of its unique position. For example, the famous footwear brand Christian Louboutin has red colour registered for the sole of its shoes[11] (

) in Class 08[10]. Further, a single colour can also be protected by way of its unique position. For example, the famous footwear brand Christian Louboutin has red colour registered for the sole of its shoes[11] ( ) and the Delhi High Court has also protected the Red Colour Sole of Louboutin Shoes and held the colour to be distinctive on the sole of a non-red shoe.[12]

) and the Delhi High Court has also protected the Red Colour Sole of Louboutin Shoes and held the colour to be distinctive on the sole of a non-red shoe.[12]

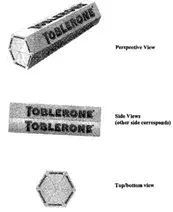

Shape marks: A trade mark can include the shape or appearance of goods or their packaging, as long as it can be visually represented, according to the Trade Marks Act. The goods sold under such a trade mark are distinguished from those offered by another manufacturer by their look and feel. Further, for a product’s shape to be registered as a trade mark, it must not serve as a functional component of the product. To safeguard its originality and identity, the Coca-Cola bottle for example, was granted trade mark for their shapes[13] ( ). Further, protection is also granted to 3-Dimensional shapes and also for the packaging of products such as the distinct shape of Toblerone Chocolate[14] (

). Further, protection is also granted to 3-Dimensional shapes and also for the packaging of products such as the distinct shape of Toblerone Chocolate[14] ( ). It is interesting to note that even the store layouts and architectural designs are being protected as trade mark. For example, the hotel Taj Mahal Palace was granted a trade mark protection for its unique architectural design. Further, many store layouts such as the layout of the famous beauty care brand Mary Cohr Store Layout[15] (

). It is interesting to note that even the store layouts and architectural designs are being protected as trade mark. For example, the hotel Taj Mahal Palace was granted a trade mark protection for its unique architectural design. Further, many store layouts such as the layout of the famous beauty care brand Mary Cohr Store Layout[15] ( ) are registered as trade marks.

) are registered as trade marks.

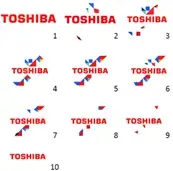

Motion marks: A motion trade mark is a moving logo that is used as part of a creative marketing plan to attract customers to the products. Any motion mark is created utilizing animation, computer programs, and any moving object. Motion marks are registered using the same criteria as other types of trade marks, but they account for a small percentage of trade mark submissions in India. When submitting a motion mark registration, the corporation or individual must remember that any movement in the mark must be depicted in the order in which it is being displayed for the product. Example of a motion mark registered in India is Toshiba ( )[16].

)[16].

Hologram marks: A hologram is a 3-Dimensional image formed by the interface of light beams. Holograms possess multiple images or colors that are visible only when viewed from different angles. Even though holograms can be very helpful in identifying the origin/source of a product through its distinctiveness, it is difficult to represent the same in written form, as the applicant would have to describe the trade mark when viewed in different angles. A famous example would be the hologram present on the American Express credit card, which is registered ().[17]

().[17]

Sound marks: In India, sound that is graphically represented by a succession of musical notes with or without words can be protected under the Trade Marks Act. If a sound is or has become a distinctive symbol connected with one undertaking, it will be granted trade mark registration under the Act. As a result, in order for a sound trade mark to be registered, the average consumer must perceive the sound as being linked with a specific service or product. Example of sound tracks registered as trade mark is Nokia (Guitar notes on switching on the device)[18].

Smell marks: Smell that is associated with a particular product and is a source identifier of the said products can be termed as a smell mark. Since depicting the smell of a product graphically is difficult, the smell marks are rarely registered. Examples of some scent marks include bubble gum scent for shoes and footwear owned by the Brazilian manufacturer “Grendene”.[19] However, due to the doctrine of functionality, olfactory marks from beauty or self-care products like cologne or perfume are ineligible for registration as a trade mark. In India, no smell marks appears to be registered till date.

Conclusion

In spite of the great importance associated with the non-conventional trade marks, there are a lot of challenges associated with the registration and enforcement of such marks. In addition to the difficulty in representing it graphically, the public also rarely identify the products or goods through the smell, sound or touch of the products as a primary indicator. In fact, these marks are most often used as secondary source to identify the products and for marketing and advertising purposes.

However, these obstacles in the way of non-conventional trade marks should be viewed as an opportunity to offer innovative approaches, rather than a discouragement to their use. India has given its approval to Intel’s sound trade mark. This paradigm change from the usual concept has commercial implications and it necessitates global uniformity. It may be deduced that non-traditional trade marks are becoming more important in contemporary times, and that adequate policies should be in place to promote and govern the use of such trade marks in India.

Sandhya A. Parimala, Associate at S.S. Rana & Co. has assisted in the research of this article.

[1] Section 2 (1)(zb), The Trade Marks Act, 1999.

[2] Rule 2(k)1 of the Trade Mark Rules, 2002.

[3] The Trade Marks Act, 1999.

[4] Section 9 of The Trade Marks Act, 1999

[5] Section 11 of The Trade Marks Act, 1999

[6] P. Narayanan, Intellectual Property Law, Third Edition, Eastern Law House, 2020, Pg:157

[7] Rule 2(1)(k), Trade Mark Rules, 2017.

[8] Section 2 (1)(zb), The Trade Marks Act, 1999.

[9] Application No. 5037338

[10] Application No. 1394234

[11] Application No. 1922048

[12] Christian Louboutin Sas v. Mr. Pawan Kumar & Ors, 12 Dec 2017.

[13] Application No. 1414264

[14] Application No. 1279340

[15] Application No. 4073262

[16] Application No. 4093005

[17] Registration No. 3045251, United States.

[18] Application No. 1365394

[19] Registration No. 4754435, United States

Related Posts

Lost in the crowd! – The generic trademarks life

By Pranit Biswas and Girishma Sai Chintalacheruvu

It is the intention and rather the duty incumbent upon every individual and/or business to ensure that their brand is striking, stands out amongst the public and has attributes to easily become familiar with the target audience. However, this is where budding businesses must tread with caution, as a brand becoming too familiar may lead to Genericide!

Generic Trademarks v. Generic Terms

‘Generic’ trademarks are those which with constant use, become so popular in the daily use of language by the public, that the mark is no longer associated with the particular business entity, and instead assumes the meaning of a particular good and/or service itself. In such cases, a mark which is originally granted registration on the basis of its distinctive character, becomes generic and eventually loses its distinctiveness. This process is known as genericization. Some examples of generic trademarks include – Aspirin, Band-Aid, Cellophane, Velcro, and Thermos; all of which have gained a generic status due to extensive use of the term, in a manner where it is interchangeably used in everyday conversation for a product identical in nature, and not necessarily associating it with the original brand.

Inversely, a mark which is originally ‘generic’ in nature, is not eligible to be protected by Trade Marks law at all, unless the Applicant successfully justifies that the said mark has acquired a secondary meaning in connection with its business. For example – a proprietor engaged in the business of perfumes, would not succeed in obtaining registration for the word mark “perfume” as the same is evidently a generic term in the context of its business. The same, if granted protection, would monopolize the entire trade and forcefully drive out the competitors from the market. However, if the proprietor sufficiently shows cause that the term “perfume” has indeed acquired a secondary meaning, then the same may be granted protection under the Trade Marks law.

Trademark Genericide

While the term trademark genericide is not defined within the Trade Marks Act, 1999, the same refers to a process of the loss of distinctiveness in a given mark over a period of time, as a result of which the mark starts to be used “generically” in the context of certain goods or services. The term Band Aid is also another example of generic trademark- it was originally acquired and registered by Johnson & Johnson. However, the mark has been used so frequently that the term Band Aid has now become synonymous with “adhesive bandages”.

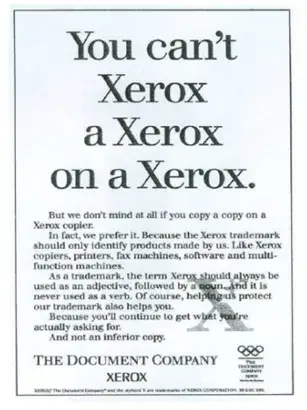

The genericization of a trademark grants free pass to other competitors in the trade to ride upon the goodwill and fame garnered by the original business entity. Much like the example of Xerox, wherein even though photocopies can now be made with machines from Canon, Ricoh or Toshiba, consumers still continue to use the term Xerox which has assumed the meaning of photocopying. The law with respect to the interests and rights of a business entity that lost its trademark to genericide, continues to remain gray.

Case Laws

The word mark ‘App Store’, coined, registered and acquired by Apple Incorporation was not granted protection in the Australian Courts, for becoming generic, within one year of its registration.[1] The Federal Court of Australia dismissed Apple’s appeal, stating that “the App Store must not be taken as not being capable of distinguishing the designated services as Apple’s services.” Some other examples include the term ‘Escalator’, which was originally registered by Otis, but the same lost its protection due to becoming generic. The mark ‘Aspirin’, which was originally adopted by a company named Bayer, also met the same fate owing to the mark being used too commonly.

In the case of Dabur India Limited vs. Emami Limited[2], the High Court of Delhi accepted that generic words cannot be granted exclusive rights, which in this case was – Chyawanprash, However, it decided on a question of law pertaining to that matter, and not on whether the Party should cease to enjoy exclusive rights over the generic word – Chyawanprash.

Further, the Madras High Court in the case of Mr. A.D.Padmasingh Isaac and M/s Aachi Masala Foods (P) Ltd vs. Aachi Cargo Channels Private Limited[3], held that granting exclusive rights over a generic term to a single proprietor would be unfair to other proprietors in the trade and the same would be against the principles of natural justice. However, the Court acknowledged the use and registration of composite generic trademarks, which refers to the combination of a generic term with other terms. The same was also accepted by the Supreme Court in the case of Parakh Vanijya Private Limited vs. Baroma Agro Product and Others[4], wherein the Court allowed the registration of a business entity looking to protect the mark ‘Baroma Malabar’, which was opposed by the appellant with ‘Malabar Gold’ as their registered trademark. In this case, the court also observed that the generic term ‘Malabar’ cannot be granted to one single business entity.

Currently Vulnerable & Companies Salvaging Genericization

Currently, there are several registered marks that are enjoying exclusive rights under the trade marks law, but are highly vulnerable to genericization. For example, “Google” is slowly becoming synonymous with looking up information on the internet e.g. – ‘Google it’, ‘Googling”, etc.

Perhaps, the current trend of using trade marks as verbs while marketing ones’ own brand helps gain instant traction, though, the same makes it highly vulnerable to fall prey to trade mark genericide, in the long run.

While some entities are busy harvesting the (rather, short term) benefits of their trade mark becoming borderline generic, several multinationals have indeed began recognizing the underlying issues that come with genericization of their trade marks and have taken active measures to prevent the same. For instance, Velcro IP Holdings LLC and trading as Velcro Companies, having the brand name VELCRO, in respect of “hook-and-loop fasteners” repeatedly urges the public to not use its trade mark interchangeably for the type of product, as they are at a high risk of losing their rights in the “trade mark”. In 2017, the official YouTube page of the brand VELCRO posted a video trying to create awareness among the public.[5]

By way of another example, to counter the effects of the term ‘Xerox’ becoming vulnerable to becoming synonymous with ‘the act of making copies of a document’, Xerox Corporation came-up with “anti-genericide” advertisements to educate the people regarding its trade mark rights over the term ‘Xerox’. For example, they introduced creative advertisements carrying taglines like – “You can’t Xerox a Xerox on a Xerox. But we don’t mind at all if you copy a copy on a Xerox® copier.” and “When you use ‘xerox’ the way you use ‘aspirin,’ we get a headache.”. Such efforts humorously and tactfully conveys to the consumers that their trade mark must not be interchangeably used.

Another noteworthy strategy includes the case of Google, where they published “rules for proper usage”[6] for all its trade marks, in order to prevent the use of “Google” as a common verb. However, the real test is the actual impact of the publication of such rules, in comparison to the strategy adopted by Xerox Corporation. For a message to have a wider outreach, the approach adopted by Xerox may reap the desired results in a better manner, as it is seldom that a user would voluntarily go into reading policies and other fine print of the like.

Genericide Prevention

One of the main reasons behind Trademark Genericide, includes the continuous use of a trademark by the public to the point where it is used to denote a particular product rather than the source. Thus, the duties of a trademark owner do not end with the “due diligence” before adopting and registering a distinctive trademark, but also goes beyond the point of registration. In other words, preventing distinctive trademarks from becoming generic very much lies in the hands of the business, which must be duly practiced. In this regard, WIPO[7] lays down certain useful guidelines to prevent trademark genericides, including:

- Using the ® symbol appropriately, upon registration

- Including consistency in the usage of the trademark, exactly as registered, and avoiding modifications. For instance, MONTBLANC® fountain pen” should not appear as “Mont Blanc”.

- Avoiding the usage of trademarks as nouns, verbs or plural forms.

- Establishing a code of conduct with respect to the usage of trademarks, within the organization.

Additionally, initiating appropriate legal action in a timely manner is as important, in order to protect one’s trademark rights.

Therefore, it is pertinent for businesses to strike a balance while promoting their trademark, so that they are advertised to the extent that they become well known, but not generic. Indeed, it is the duty of the respective businesses to identify and adopt best practices that could possibly prevent the genericization of their trademarks. They must understand the consumer perception of their mark, and take appropriate steps to counter any practice that may lead towards trademark genericide.

[1] Apple loses appeal for australian app store trademark

[2] 112 (2004) DLT 73

[3] AIR 2014 Mad 2

[4] AIR 2018 SC 3334

[5] Click Here

[6] The trademark only as,artwork when using Google’s logos.

[7] Page 60, Making a Mark – An Introduction to Trademarks and Brands for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (WIPO Publication) – An Introduction to Trademarks and Brands for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (WIPO Publication)

Related Posts

C.A.R.T- Can Acronyms be Registered as Trademarks?