By Shilpi Sharan and Pallavi Paul

Introduction

In Pernod Ricard India Private Limited & Another. v. Karanveer Singh Chhabra[1], the Hon’ble Supreme Court in a judgement dated August 14, 2025 refused to grant relief to Pernod Ricard against a Madhya Pradesh-based whiskey manufacturer accused of infringing its ‘Blenders Pride’ and ‘Imperial Blue’ trademarks by marketing whiskey under the name ‘London Pride’.

Brief Background of the Case

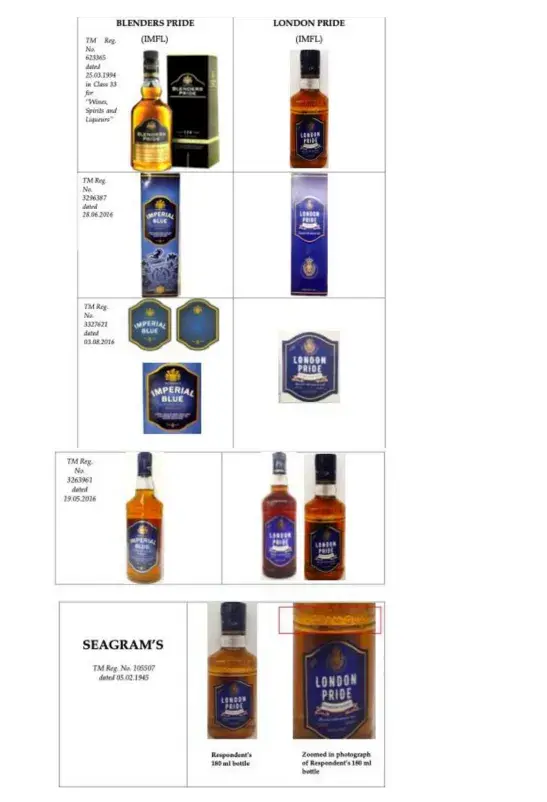

Pernod Ricard, manufacturer of premium whiskeys like ‘Blenders Pride’ and ‘Imperial Blue,’ brought suit against Karanveer Singh Chhabra, marketer of ‘London Pride’ whiskey. Pernod Ricard alleged trademark infringement, passing off, and copyright violation, seeking an interim injunction to restrain Karanveer Singh Chhabra from using ‘London Pride,’ whose branding and packaging were claimed to be deceptively similar to its famous marks.

Pernod Ricard alleged that its two whiskey brands have gained a significant amount of goodwill and reputation wherein the word ‘Pride’ being the most unique component of its trademark ‘Blenders Pride’.

The competing marks as depicted in the judgement is copied below:

Series of Hearings

Both the Commercial Courts of Indore and the Madhya Pradesh High Court rejected Pernod Ricard’s plea for an interim injunction, holding that there was no likelihood of confusion or deceptive similarity between the competing marks, and observed as follows:

- The word ‘Pride’ is publici jurise., common to the trade;

- Marks should be taken as a whole while making comparisons;

- The packaging, style, bottle shape, and logos of the two competing brands were entirely different. Further, Pernod Ricard’s bottle bore the embossing ‘Seagram Quality’ and labels of the competing products carried distinct names and logos;

- The competing brands relate to ‘premium’ or ‘ultra-premium’ whiskey and the consumers of these products can reasonably be presumed to be literate and possess sufficient intelligence to distinguish between the brands. Reference was made of the Khoday Distillers Limited v. The Scotch Whisky Association[2] case that held that the test of deceptive similarity should be applied differently in each case, depending on the type of customers who are likely to purchase those goods.

Key Issues for Consideration

The key issues before the Hon’ble Supreme Court were the following:

- Whether ‘London Pride’ infringes the registered trademarks/blends the goodwill of ‘Blenders Pride’ and ‘Imperial Blue’;

- Whether an interim injunction should be granted against the use of ‘London Pride’;

- What is the appropriate test for deceptive similarity in cases of composite marks and generic terms.

Hon’ble Supreme Court’s Analysis

- Anti-Dissection Rule and Composite Marks: The Court reiterated the anti-dissection rule that trademark similarity must be assessed by considering the mark as a whole and not by dissecting it into individual elements like ‘Pride’. The Court found that ‘Blenders Pride’ and ‘London Pride’ differ significantly when considered in their entirety i.e., visually, phonetically, and conceptually.

- No Monopoly over Generic or Laudatory Words: The judgment strongly affirmed that generic, descriptive, or laudatory expressions such as ‘Pride’, cannot be monopolized unless they have acquired secondary meaning. The Court noted that the word ‘Pride’ is widely used across liquor industry and not distinctive to Pernod Ricard. The Supreme Court also relied on earlier failed attempts by Pernod Ricard to claim exclusivity over ‘Pride’, most notably in Pernod Ricard India Private Limited v. United Spirits Ltd.[3] where Pernod India had sought to restrain United Spirits from using the mark ‘Royal Challenge American Pride’. The Court had then held that Pernod India had no independent registration over the word ‘Pride’ but only over the composite mark ‘Blenders Pride’.

- The Average Consumer Test: The likelihood of confusion must be analysed from the applicable standard of an average consumer with imperfect recollection. In this case, as both products targeted premium consumers who exercise care in their purchases, the risk of confusion was further diminished.

- Rejection of Hybrid Claims: The Court criticized Pernod Ricard for improperly combining features from separate marks (‘Blenders Pride’, ‘Imperial Blue’ and bottle designs) to create a hybrid infringement claim and stated that each mark must be assessed independently, not through aggregation of different features.

- Balance of Convenience and Irreparable Harm: The Court found no prima facie case or likelihood of irreparable harm sufficient to grant interim injunction, especially since the elements alleged to be copied (like the word ‘Pride’, or use of certain colour scheme) were generic or unsuccessful in previous litigations. The Commercial Court’s findings that bottle and labels were different, and that there was no evidence of actual confusion or misuse of proprietary bottle embossing (Seagram quality), were upheld.

- Directions for Expeditious Trial: The Court ordered the Commercial Court to proceed with the main suit and dispose of it within four months, admonishing delays in IP litigation and reiterating that interim decisions must not prejudice the final trial.

The developing doctrine of Post-sale confusion in the United Kingdom

The Court mentioned regarding the doctrine of post-sale confusion, which is an evolving concept in trademark law, recently affirmed by the UK Supreme Court in the landmark case Iconix Luxembourg Holdings SARL v Dream Pairs Europe Inc.[4]

- Post-sale confusion refers to consumer confusion that arises not at the point of sale, but rather after the product has been purchased and is in use publicly. For example, when someone buys a product bearing an allegedly infringing trademark, and others who see the product later are misled into associating it with the original brand, even if the purchaser was not confused when buying it.

- However, this doctrine is relevant in sectors like fashion, luxury goods, automobiles, and food items, where brand visibility and public perception are essential aspects of consumer engagement and brand equity.

- Therefore, in the present case, the goods in question are not intended for public display and are for private consumption. Therefore, the doctrine of post- sale confusion, while significant, is not directly applicable to the facts of this this case.

Interpretation of Section 15 and Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act in this judgement

In this judgment, the Hon’ble Supreme Court interpreted Section 15 of the Trademarks Act, 1999 as establishing a clear requirement for claiming exclusive rights over parts of a trademark.

The Court explained that Section 15(1) mandates that if a trademark owner wants to claim exclusive rights over any individual part or component of their registered mark, they must separately register that specific part as an independent trademark. The section does not automatically grant protection to individual elements within a composite mark.

The Court also emphasized that Section 15 works in conjunction with Section 17 to ensure that trademark owners cannot claim monopoly over common or descriptive terms unless they have registered those terms separately. In the present case, since Pernod Ricard had only registered ‘Blenders Pride’ as a composite mark and had not separately registered the word ‘Pride’ under Section 15(1), therefore, they could not claim exclusive rights over that individual component.

This interpretation reinforces the principle that trademark law protects the whole registered mark, not its constituent parts, unless those parts are independently registered.

Conclusion

This judgment reaffirms that trademark law, while protective of brand identity and goodwill, does not extend exclusivity over laudatory, descriptive, or generic elements, absent proof of acquired distinctiveness through secondary meaning. The Hon’ble Court reaffirmed the principles of the anti dissection rule and the average consumer test, emphasizing that likelihood of confusion must be assessed on the overall impression of competing marks rather than by isolating generic components. With premium goods at issue, such as whiskey, the Hon’ble Court recognized that consumers are typically more discerning, further reducing the risk of confusion in such markets.

This judgment is a clarion call for trademark owners to focus on strengthening the distinctiveness of their brands as a whole, rather than seeking proprietary rights over generic or descriptive substrings.

[1] CIVIL APPEAL NO. 10638 OF 2025 [Arising out of SLP (C) No. 28489 OF 2023]

[2] 2008 (10) SCC 723

[3] 2023 SCC OnLine P&H 477 : (2023) 3 RCR (Civil) 162

[4] [2025] UKSC 25