By Anuj Dhar and Aashi Nema

Introduction

In a significant ruling on comparative advertising and product disparagement, the Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court in Emami Limited v. Dabur India Limited dismissed Emami’s appeal against Dabur’s advertisement for its product “Cool King.” The dispute revolved around the alleged disparagement of Emami’s well-known prickly heat powders, Dermi Cool and Navratna in a television and social media commercials. The Hon’ble Court, while balancing the principles of disparagement with the constitutional protection of commercial free speech, held that mere use of the word “Sadharan” (ordinary) and depiction of a generic bottle did not amount to actionable disparagement.

This case offers important guidance on the threshold for proving disparagement in comparative advertising, the concept of recall value in consumers minds, and the scope of injunctions in intellectual property disputes.

Background and Facts of the Case

In 2024, Emami Limited, the manufacturer of the well-known prickly heat powders Dermi Cool and Navratna, raised objections against a television and social media advertisement released by Dabur India for its new product Cool King. Emami’s concern was that the commercial did not merely promote Dabur’s product but also cast its own brands in a negative light.

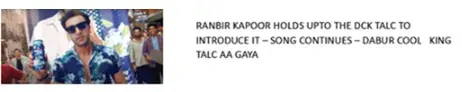

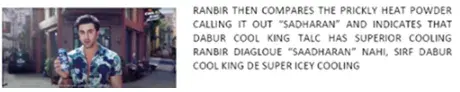

The advertisement showed people suffering in the heat, one of whom was carrying a bottle that, according to Emami, closely resembled its distinctive packaging with a tapering shape and green slanted cap. In the commercial, the actor described this bottle as “Sadharan” (ordinary) and immediately presented Dabur’s Cool King as the better alternative, leading the protagonist to abandon the earlier bottle. A few snippets of the Impugned advertisement can be seen from below snapshots:

Emami’s Arguments

Emami argued that this depiction amounted to disparagement because consumers would naturally associate the so-called “sadharan” bottle with its products, thereby damaging their reputation and goodwill. Emami also pointed out that recall value in the public perception is high thus, people would immediately connect the denigrated bottle with that of the Appellant’s products, thereby harming goodwill and reputation.

Dabur’s Arguments

Dabur responded that the bottle shown in the commercial was a simple cylindrical design with a black cap, very different from Emami’s unique trade dress. It also maintained that the word “Sadharan” was used only in a generic comparative sense to highlight its product and not as an insult to competitors. Dabur further argued that Emami has not complained of any infringement of the trademark of its bottle, nor does it have any trademark rights on the colour of the cap.

Proceedings So Far

After considering these arguments, the Single Judge modified the injunction granted on July 11, 2024, against Dabur, thereby restraining them from airing advertisements that displayed bottles resembling Emami’s packaging. The modification dated January 17, 2025, clarified that the restraint would apply only to the impugned advertisement as a whole and that the mere use of the word “ordinary” without directly identifying Emami’s products could not be treated as disparagement.

Dissatisfied with this modification, Emami carried the matter in appeal before the Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court, which resulted in the present Appeal.

Legal Issues Considered by the Hon’ble Court and its Subsequent Findings

The Division Bench examined three broad questions: whether the advertisement could reasonably be connected with Emami’s products, whether the word “Sadharan” amounted to disparagement, and whether the injunction required modification.

- Similarity of Bottles:

The Court compared the two bottles and found them “markedly different.” Emami’s packaging had a tapering design with a green cap and notch, whereas the bottle in Dabur’s commercial was cylindrical with a flat black cap. To an average consumer, the Court said, there was no real chance of mistaking one for the other. - Recall Value:

Emami argued that, as a market leader, its products enjoyed such recognition that consumers would automatically connect the disparaged bottle with Dermi Cool or Navratna. The Court rejected this. It reasoned that since six months had passed between the earlier advertisement and the current version, an ordinary consumer was unlikely to recall the old version and then connect it to Emami’s products. Such “double recall,” as the Court put it, was unrealistic. - Meaning of “Sadharan”:

The Bench held that calling a product “sadharan”, in a comparative sense should not be equated with “inferior”. The Court emphasized that disparagement requires more than suggesting one product is better; it must involve some form of ridicule or defamation of the competitor’s product. Here, the actor did not discard the earlier bottle in a derogatory way, nor was there any claim that Emami’s product was harmful. Instead, the ad only highlighted Dabur’s product as superior.In this respect, the Division Bench referred to the case Reckitt & Colman of India Ltd Vs. MP Ramchandran (1999) 19 PTC 741, wherein it was held that “it is permissible to portray that the advertiser’s product is the best in the world. However, what is shunned is the direct or indirect denigration of the product of another manufacturer.” - Freedom of Commercial Speech:

The Court balanced Emami’s right to protect its goodwill with Dabur’s Constitutional right under Article 19(1) (g) of commercial free speech and advertisement. Relying on earlier cases, the Bench reiterated that an advertiser is allowed to boast about its product and even claim it to be the best, provided it does not directly belittle a rival’s goods.The Court also referred to a notable ruling of Hon’ble Delhi High Court in Dabur India Limited Vs. Colgate Palmolive India Ltd., (2005) 79 DRJ 461. In this case, the word “Sadharan” was used for a tooth powder (dant manjan), but coupled with the claim that such “Sadharan” dant manjan was abrasive and rough on the teeth. Therefore, Colgate was restrained from disparaging Dabur’s product in a television commercial. - Scope of Injunction:

The Division Bench found that the modified order of the Single Judge actually gave Emami more protection, since it restrained the airing of the impugned advertisement in its entirety. The Court also clarified that dynamic injunctions against all possible future ads would be unworkable; each new advertisement must be judged on its own facts.

Judgment of the Court

The Division Bench dismissed Emami’s appeal and affirmed the Single Judge’s modified order dated January 17, 2025. It concluded that the impugned advertisement did not amount to disparagement and that Dabur’s use of the term “Sadharan” was permissible in the context of comparative advertising. The Court also held that the injunction granted was adequate and enforceable, and declined to extend it into a blanket ban on future advertisements. The appeal was therefore rejected without costs, leaving the parties free to contest the matter fully at trial.

Author’s Note

The decision of the Calcutta High Court in Emami v. Dabur provides much-needed clarity on the limits of comparative advertising in India. The ruling makes it clear that while companies are free to highlight the strengths of their own products, they cross the line only when their advertisements directly ridicule or defame a competitor’s goods. Mere use of generic expressions like “Sadharan” or broad comparisons will not, by themselves, constitute disparagement.

For commercial advertisements, this case is a reminder to design marketing campaigns with care; creativity and puffery are allowed, but direct denigration is not. It reinforces the principle that disparagement must be proved with clear and specific evidence, not assumptions about consumer perception. The judgment also provides assurance that while advertisers may boast about their products, the law prevents them from unfairly running down others.

Overall, the ruling strikes a balance between safeguarding brand reputation and protecting the freedom of commercial speech, ensuring that competition in the marketplace remains both fair and robust.

Also refer to: