By Vikrant Rana, Huda Jafri

Introduction

On November 21, 2025, the Indian trademark landscape underwent a transformative shift when the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks (CGPDTM) accepted, for advertisement, India’s first-ever olfactory trademark application. The applicant, Sumitomo Rubber Industries Ltd. of Kobe, Japan, sought protection for a scent mark described as “Floral Fragrance / Smell Reminiscent of Roses as Applied to Tyres” under TM Application No. 5860303, filed on March 23, 2023 for goods falling in Class 12.[1]

This development is remarkable for several reasons. First, India’s Trademarks Act, 1999, unlike some modern statutes, contains no express reference to smell marks. Second, Indian trademark practice has historically revolved around visually perceptible marks, words, logos, labels, shape marks, and even color combinations. Third, smell marks globally have faced resistance due to the inherent difficulty in generating a graphical representation that is “clear, precise, self-contained, durable and objective,” as required by international jurisprudence such as Siekmann.[2] (Read more about the case)

The CGPDTM’s order marks the first instance of successful reconciliation of these statutory and practical challenges in India. In doing so, the decision aligns Indian practice with jurisdictions such as the EU, UK, Australia, and the USA, yet innovates through the acceptance of a 7-dimensional scientific olfactory vector, a first-of-its-kind approach in trademark representation worldwide.

Submissions of the Applicant

The applicant’s submissions reflect a well-strategized attempt to address both statutory limbs under Section 2(1)(zb): graphical representation and distinctiveness. Their arguments were built upon commercial history, statutory interpretation, and a pioneering scientific method designed specifically to meet the Act’s requirements.

- Commercial History and Branding Strategy

Sumitomo Rubber Industries explained that it has infused tyres with a rose-like fragrance since 1995. The fragrance was not an incidental by-product but a deliberate branding initiative, designed to eliminate the unpleasant rubber odor typically associated with tyres and to create a distinctive sensory experience.

By highlighting nearly 30 years of commercial use, the applicant established that:- The smell was intentionally designed as a brand signifier,

- Consumers encounter it as a non-functional attribute, and

- The scent has long contributed to the overall identity of the product.

This contextual background reinforced the applicant’s claim that the fragrance functions as a source identifier.

- The Statutory Definition of “Mark” Under Section 2(1)(m)

The applicant placed significant reliance on the inclusive nature of Section 2(1)(m). By using the term “includes,” the legislature opened the definition to marks not explicitly listed—allowing the trademark system to adapt to advancements in marketing and technology.The applicant argued:- The Act does not restrict trademarks to visual or verbal forms,

- It does not exclude smells or other sensory signs, and

- As long as the sign satisfies graphical representation and distinctiveness, it is eligible for protection.

Thus, the issue before the Registry was not whether smells can be marks, but whether this particular scent meets the statutory criteria.

- Graphical Representation: Dual Strategy

Anticipating the Registry’s concerns, the applicant submitted two forms of graphical representation:- The Verbal Description

The mark was described as: “Floral Fragrance / Smell Reminiscent of Roses as Applied to Tyres.”The applicant argued that:- The scent of roses is universally recognizable,

- The phrase captures a well-known aromatic profile, and

- The description is sufficiently clear and stable.

However, the applicant did not rely on the verbal description alone.

- The Scientific Olfactory Vector

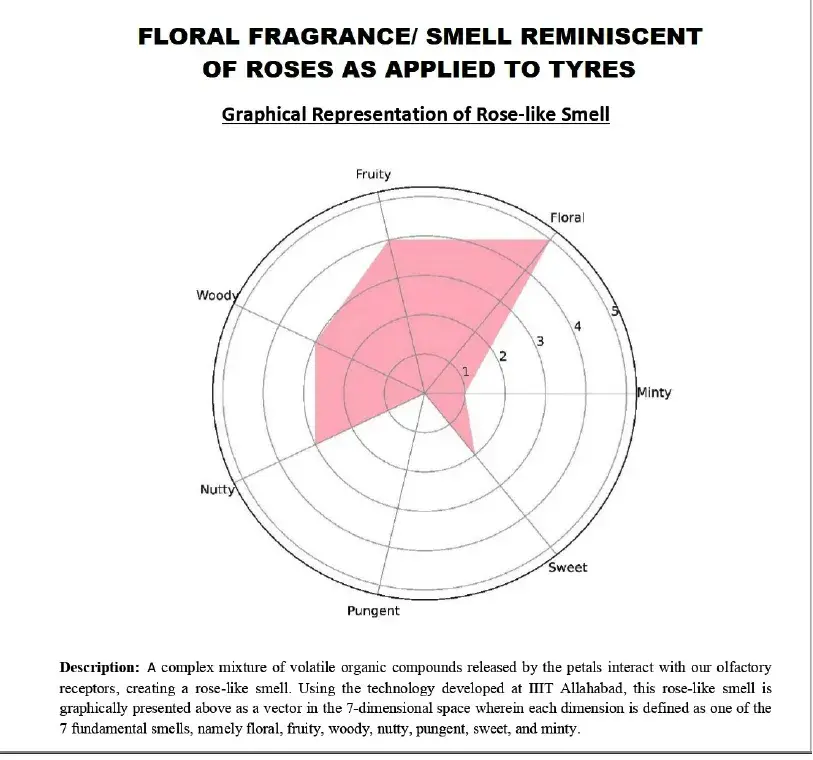

The applicant submitted a seven-dimensional olfactory graph developed by scientists at IIIT Allahabad[3]. This model identifies the top volatile organic compounds (VOCs) comprising the rose scent and plots them across seven olfactory axes:

Source:

https://tmrsearch.ipindia.gov.in/eregister/eregister.aspx The model blends chemistry, sensory science, and machine learning to produce a precise, durable, and self-contained representation of the fragrance.The applicant argued that this method satisfies all attributes demanded of graphical representation: clarity, precision, intelligibility, objectivity, and durability.

- The Verbal Description

- Distinctiveness Under Section 9(1)(a)

The applicant submitted that:- Floral scents have no functional relation to tyres,

- The scent of roses is arbitrary in this market context,

- Consumers will immediately perceive the fragrance as intentional and origin-indicating, and

- The scent is memorable, enhancing brand recognition.

This, they argued, satisfies inherent distinctiveness.

- Persuasive International Evidence

The applicant emphasized its earlier UK registration: UK00002001416 (registered in 1996), for the very same scent. This was the first smell mark approved in the UK, demonstrating international acceptance and reinforcing distinctiveness. - Foreign Jurisprudence and Comparative Examples

To strengthen its argument, the applicant cited:- the EU “fresh cut grass”[4] mark,

- multiple US registrations of non-functional scents,

- several Australian smell marks, and

- a list of 26 olfactory marks registered globally.

These examples established that global trademark law recognizes scents as protectable subject matter.

Submissions of the Amicus Curiae

To ensure an informed and balanced decision, the CGPDTM appointed Shri Pravin Anand as amicus curiae. His submissions provided critical clarity on both legal doctrine and scientific applicability.

- Core Legal Issues

The amicus identified two essential legal questions:- Does the scent of roses have the capacity to distinguish the applicant’s goods?

- Can the scent be represented graphically in a manner compliant with the Act?

These questions framed the CGPDTM’s evaluation.

- Global Treatment of Smell Marks

The amicus surveyed international practice, noting that:- The United States protects non-functional scents,

- The UK has previously registered the applicant’s scent,

- The EU recognizes scent marks under strict standards,

- Australia explicitly accommodates olfactory signs.

- The amicus also submitted an extensive list of smell marks from various jurisdictions, demonstrating that smell marks, though rare, are not unprecedented internationally.

- Scientific Representability

The amicus elaborated on the seven-dimensional model created by IIIT Allahabad. The model identifies the primary VOCs that constitute the rose scent and quantifies each in terms of olfactory strength. The graph thus becomes a scientifically reproducible “scent fingerprint.”

He submitted that this representation meets the criteria of:- Clarity: identifiable axes and numeric parameters,

- Precision: quantification of each olfactory dimension,

- Objectivity: based on empirical data,

- Durability: no risk of degradation over time,

- Intelligibility: readable by examiners and third parties.

- Distinctiveness

The amicus reiterated that a rose fragrance has no functional relevance to tyres, making it inherently distinctive and capable of indicating origin.

Analysis by the CGPDTM

The CGPDTM’s analysis reflects a balanced combination of statutory interpretation, scientific assessment, and comparative reasoning.

- Interpretation of “Mark”

The Controller highlighted that Section 2(1)(m) uses the term “includes,” signaling legislative intent to permit the evolution of marks beyond traditional categories.

Thus, the Act can accommodate scents if statutory thresholds are met - Requirements Under Section 2(1)(zb)

The scent had to satisfy:-

- Capability of graphical representation, and

- Capability of distinguishing goods.

The CGPDTM analyzed each requirement distinctly and in detail.

-

Graphical Representation

This was the most significant hurdle historically faced by olfactory marks.

- Inadequacy of Conventional Methods

The CGPDTM acknowledged that earlier global attempts, such as written descriptions, molecular formulas, and scent samples, failed because they lack one or more of:- clarity

- durability,

- objectivity

- precision.

Thus, the Registry turned to the applicant’s scientific solution.

- Acceptance of the Seven-Dimensional Olfactory Vector

The CGPDTM found that the vector:- visually captured the scent profile,

- provided quantitative precision,

- relied on VOCs,

- was durable and reproducible, and

- was durable and reproducible, and

This acceptance is unprecedented in India and sets a benchmark for future non-traditional trademark filings.

Distinctiveness

The CGPDTM held that the scent is inherently distinctive.

-

- Arbitrary Association: The rose fragrance bears no natural or functional relationship to tyres. Arbitrary marks are the strongest category of inherently distinctive signs.

- Consumer Perception

The order emphasised that consumers:

-

- do not expect floral scents in tyres,

- are likely to perceive the scent as intentional,

- will associate it with a single source, thus enabling brand recall.

- Persuasive International Practice: The earlier UK registration reinforced the scent’s validity and distinctiveness.

Final Determination

The CGPDTM concluded that:

- The scientific model satisfies graphical representation,

- The scent is inherently distinctive,

- The mark qualifies as a trademark,

The application is to be advertised as an Olfactory Trademark under Section 20.

Conclusion

This decision is a watershed moment in Indian trademark jurisprudence, not because it follows international practice, but because it advances it. The CGPDTM has created a new legal standard for representing smells graphically, using scientific data visualization rather than linguistic approximation. It marks the beginning of a jurisprudential shift where sensory experiences beyond sight and sound can now be formally recognized as trademarks in India.

The order is not merely administrative acceptance, it is the foundation of an entirely new category of trademarks, supported by statutory interpretation, scientific rigor, and comparative sensitivity.

[1] file:///C:/Users/huda/Downloads/Smell-mark-Order-Signed-by-CGPDTM.pdf

[2] Ralf Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent and Markenamt, Case C-273/00, 12 December 2002, European Court of Justice.

[3] Indian Institute of Information Technology, Allahabad

[3] Vennootschap Onder Firma Senta Aromatic Marketing v. Markgraaf B.V., dated 11.02.1999,