Videogames have come a long way since the days when Mario, Contra and Half-Life were played, and gone are the days when videogames were played by children only. If statistics are to be believed, about 29 percent of game players are below 18 years of age, whereas 39 percent of game players are 36plus years. Videogames are no longer just a popular medium of entertainment among teenagers—even adults are hooked.

Today, the market is flooded with consoles (Sony Playstation, Microsoft Xbox, and Nintendo Wii to name the most popular ones) offering a plethora of choices to gamers. The gaming industry has been advancing at a phenomenal rate so states the Entertainment Software Association, which remarks that no other sector has experienced the same explosive growth as the videogame industry.

Modern videogames are said to consist of highly dynamic audio-visual elements (including pictures, video recordings and sounds) and software, which technically manages the audio-visual elements and permits users to interact with the different elements of the game. These elements in video games present complex issues of authorship, as they are also protected by various forms of intellectual property.

The rules of the game

Videogames, primarily being works of imaginations and ideas, seek protection under intellectual property laws to avoid violations.

Each game contains distinguishable expres- sions of ideas, which if not protected may be vulnerable to infringement by another. Article 2 of the Berne Convention in its expression of “literary and artistic work” accords protection to videogames by way of copyright.

The various creative elements in a particular videogame represent different forms of IP rights. For example: patent law covers matters such as game play design elements, networking or design database; trademark law protects company names, game titles or sub-titles; and copyright subsists in works such as music, characters or code. As a result, videogames present a complex bundle of intellectual property.

A World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) publication (Legal Status of Video Games: Comparative Analysis in National Approaches, 29 July 2013) states that there is a legal controversy revolving around the classification of videogames and it is un- certain whether they fall under the purview of multimedia work, audio-visual work or a computer program.

Global perspective

Copyright does not subsist in the ideas or func- tional aspects of videogames. However, they can cover the expression of ideas. In this regard, the US Copyright Office specifically states:

“Copyright does not protect the idea for a game, its name or title, or the method or methods for playing it. Nor does copyright protect any idea, system, method, device, or trademark material involved in developing, merchandising, or playing a game.”

Once a game has been made public, noth- ing in the copyright law prevents others from developing another game based on similar principles. Copyright protects only in the par- ticular manner of an author’s expression in literary, artistic, or musical form. Thus, copy- right law protects the game code, music, characters images, scenes, dialogues.

Tetris Holding v Xio Interactive involved a copyright issue in videogames. In this case, the plaintiff, creator of the popular Tetris game, brought a suit against the defendant, creator of the game Mino, on the grounds that the defendant copied the ideas of Tetris by using similar blocks in same configuration. The plaintiff also asserted federal copyright and trade dress claims.

The court decided in favour of Tetris, holding that the defendant had infringed the copyright protecting Tetris by creating a game with a look and feel nearly identical to Tetris, and had copied protectable elements of expression in Tetris.

In videogames, the game titles, subtitles or character names such as Pokemon can be pro- tected under trademark law. Copying an iden- tical or even a confusingly similar game name can be an issue of trademark infringement.

An interesting recent example concerning the issue of trademarks in videogames is the case of The Candy Crush Saga, wherein King.com held the a registration for the term ‘Candy’ in the EU. According to Forbes, King. com issued takedown notices to various games using the term ‘Candy’. One such notice was received by the developer of the game All Candy Casino Slots-Jewel Craze Connect, wherein King.com alleged trade- mark infringement and damage to its brand.

The Indian industry

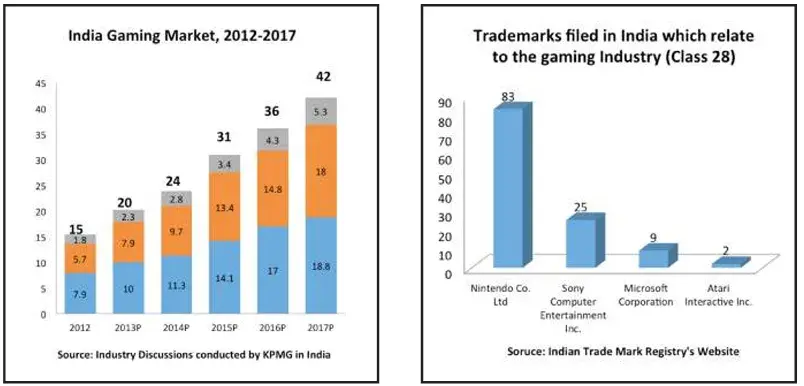

The videogame industry in India is expected to grow in the near future. According to the Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2013, the Indian videogame indus- try recorded a growth of 17.7 percent and is expected to record a growth of 22.4 percent by 2017. The Indian videogame scenario is growing gradually, with more and more do- mestic game developers and Indian game titles entering the market.

However, compared to its western counter- parts the Indian gaming industry is still min- iscule but statistics indicate that it is in- creasing in size and is expected to experience healthy growth in future.

Copyright

The Copyright Act of 1957 does not specifical- ly deal with the nuances of videogames and the lack of any precedents or regulations in this regard further aggravates the uncertainty.

However, the act under Section 2(c) defines “cinematograph film” as any work of visual recording, on any medium produced through a process from which a moving image may be produced by any means, and includes a sound recording accompanying such visual recording. ‘Cinematograph’ should be con- strued as including any work produced by any process analogous to cinematography including video films. It is uncertain whether ‘process analogous to cinematography’ refers to videogames.

Also, in terms of assignment and licence rights under the Copyright Act, a videogame can be based on a novel, comic, movie or a book and the same can be done by obtain- ing a licence from the authors of the original content. Under the Indian scenario, a video- game developer can create its game based on a movie or book by securing a commercial licence from the authors.

Trademarks

In the case of videogames, trademarks can be used for protecting the title, sub-titles of the game, or the name of characters. For ex- ample, famous videogames such as Super Mario, Tetris and The Legend of Zelda have been successfully registered with the Indian IP Office. So, if such marks are infringed by a similar or a deceptively similar mark, then relief can be obtained under Sections 29 and 135 of the act.

Patents

Patent law can be used for protecting the program code of the game, but software per se is not patentable in India. Moreover, under the Indian Patent Act of 1970, Section 3(m) specifically excludes game designs as pat- entable inventions and provides that a mere scheme or rule or method of performing a mental act or method of playing a game is not patentable. The same was also held by the Delhi High Court in the case of Mattel v Jayant Agarwalla in 2008.

Movies and videogames

There are several movies that have been adapted from videogames. For example, the movie Super Mario Bros was an adap- tation of Nintendo videogames of the same name. Similarly, there are a few videogames that have been created based on movies or books. Dhoom 3 and Sholay: Bullets of Jus- tice are based on famous Bollywood movies Dhoom 3 and Sholay.

Adaptations would fall under the acquisition of rights to make a derivative work or by ob- taining a licence from the author. For exam- ple, the American videogame developer Elec- tronic Arts (EA) obtained a licence to the Lord of the Rings trilogy to make the game The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle Earth.

Personalities and videogames

Celebrities and famous personalities are widely used as characters in videogames worldwide. In India, games such as Namo Run Attack and Super Namo featuring newly elected India Prime Minister Narendra Modi gained popularity during the recent elections.

However, using images and names of celebrities without their authorisation can lead to the infringement of their privacy and personality rights, thereby even result- ing in the withdrawal of such games by the game developer and payment of damages in case of defaming the celebrity.

How far is too far?

Indian games featuring Hindu deities have attracted substantial controversy among In- dians on the ground that it is not acceptable to reduce them to gaming characters. For instance, the game Hanuman: Boy Warrior, featuring Hindu God Hanuman, attracted ob- jection from Hindu leaders worldwide, along with demands to withdraw the game.

Similarly, the game Smite, developed by Hi- Rez studios, attracted controversy as it featured Hin- du deities Kali, Vamana and Agni.

Another instance attracted media attention was the Indian Mario Singh by MangoFroot, which was essentially Nintendo’s Mario with a turban and minor colour tweaking.

Though this may have amounted to potential copyright infringement, the original authors did not take action against it.

The videogame industry is still a developing one and Indian developers are entrusted by international publishers with the job of developing games.

Outsourcing game development is highly prevalent and there are very few entities in India that develop their own videogames. The lack of any specific legislation and precedents for the protection of various elements of videogames poses a big challenge for the industry.

Creative elements in videogames

Audio Elements: musical compositions, sound recordings, voice imported sound effects, and internal sound effects.

Video elements: photographic images, digitally captures moving images, and animation text.

Computer code (source and object code): primary game engine or engines, ancillary code, plug, and comments.

Indian markets