By Nihit Nagpal and Apalka Bareja

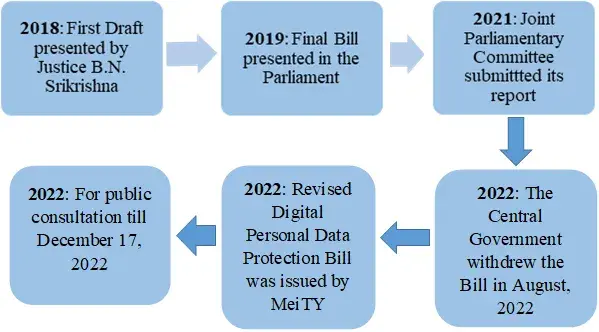

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (“MeIT”) recently introduced a revised Bill for the protection of digital personal data titled as “The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022” (hereinafter referred as “2022 Bill”). The 2022 Bill has been introduced by replacing the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (hereinafter referred as “2019 Bill”). The government displayed the Bill on its website for seeking chapter-wise feedback till December 17, 2022. It has been a constant endeavor of the Indian government to setup a regulatory mechanism which strikes a balance between “protection of personal data” and “establishment of a regulatory mechanism” which allows the processing and storing of personal data by fiduciaries. In the recent past, European Union’s Regulation, General Data Protection Regulations have often been referred to as Model law for incorporating a domestic legislation.

The 2022 Bill covers a very narrow spectrum of personal data protection unlike the previous Bills. The 2022 Bill specifically focuses on the digital data which is of personal nature. The Bill succinctly provides for 30 Sections which cover the rights of a data fiduciary, rights and duties of a data principal, establishment of Data Protection Board of India, etc. While the enactment of a legislation on protection on personal data is the need of hour, however, the present 2022 Bill still poses few challenges and issues.

Key features of the 2022 Bill vis-a-vis 2019 Bill and GDPR

The revised 2022 Bill provides for various salient features which were not covered in the previous Bills. A comparative analysis of the 2022 Bill along with 2019 Bill and General Data Protection Regulation[1] has provided herein below:

1. Extent and Applicability

| 2022 Bill | 2019 Bill | GDPR |

| Section 4 provides for the extent and applicability of the Bill only to those personal data which are collected in digital form. It also extends to such data which may be have been collected through offline mode, but have been digitized.

However, the Bill excludes some digital personal data such as: non-automated processed personal data, offline personal data, personal data processed by an individual for personal or domestic work, or personal data which has been in record for 100 years. |

This Bill was wider in its extent and applicability. Section 2 stated that it shall apply to processing of “personal data”. This implies that any personal data which is collected either through online mode or offline mode shall be covered within the ambit of the Bill.

|

Upon perusal of the preamble and various provisions, the GDPR applies to personal data. Such a personal data could be stored in physical or digital form. Therefore, the extent and applicability of GDPR over protection and processing of personal data is wide.

|

2. Reference to an individual

| 2022 Bill | 2019 Bill | GDPR |

| The revised Bill uses the word “her” under various provisions for referring an individual. This is a progressive step, and it should be used refer to all individuals irrespective of their gender.

For instance, Section 6 states: “On or before requesting a Data Principal for her consent, a Data Fiduciary shall give to the Data Principal an itemised notice in clear and plain language containing a description of personal data sought to be collected by the Data Fiduciary and the purpose of processing of such personal data.” |

This Bill followed the previous legislative drafts and used the word “his” under various provisions for referring to an individual. | The expression “natural persons” has been used to refer to an individual. The European Parliament has adopted a neutral approach to address an individual in their legislative framework. This makes the law more inclusive and easily include transgenders as well. |

3. Introduction of ‘Consent Managers’ and their accountability

| 2022 Bill | 2019 Bill | GDPR |

| The revised Bill has introduced that “Consent Manager” shall be accountable towards the Data Principal which shall act on behalf of the Data Principal, and every consent manager shall be registered with the Data Protection Board. The same has been provided under Section 7. | Section 21 of the Bill stated that the Data Principal can exercise their right through Consent Manager, however, no accountability of such manager was created towards the Data Principal. | The GDPR does not specifically provide for consent managers, however, there are controllers and data protection officers who are entrusted with such jobs. The controller is duty bound to demonstrate that data subject has given his consent. |

4. Grounds for processing Personal Data without consent

| 2022 Bill | 2019 Bill | GDPR |

| Section 5 of the Bill states that the grounds for processing personal data would be only for lawful purpose for which the Data Principal has given consent, in accordance with the provisions of the Act and Rules made thereunder.

The revised Bill does not provide for a comprehensive list of grounds under which a Data Principal can collect digital personal data without the consent of the Data Fiduciary. |

Chapter III provided for processing of personal data without consent. Section 12 to 15 provided for the list pertaining to situations where the Data Fiduciary can collect data without the consent of Data Principal.

A data fiduciary could collect personal data without the consent of Data Principal in cases where it is required for the function of the State authorized by law, for compliance of an order of a Court or Tribunal, to undertake any measure for providing medical treatment, etc. |

Article 7 makes it obligatory for the controller to process only that data which is based on consent and the controller shall be able to demonstrate the same. Further, the GDPR allows the collection personal data without consent only if collection is required for public interest in the areas of public health. Such a collection shall be subject to suitable and specific measures so as to protect the rights and freedoms of natural persons. |

5. Obligations of Data Fiduciary

| 2022 Bill | 2019 Bill | GDPR |

| Chapter 5 provides for the role of Data Fiduciary. The Central government shall guarantee notification of any data fiduciary or class as Significant Data Fiduciary (SDF) on the basis of various factors such as risk involved, volume of sensitivity and other related elements.

Further, the Data Fiduciary shall be responsible for compliance of the provisions of this Bill, specifically in matters concerning the technical and organizational aspects.

|

Chapter II provided for obligations of Data Fiduciary. Section 10 provided for the accountability of data fiduciary. However, no classification existed between Data Fiduciary and a Significant Data Fiduciary (SDF). | The GDPR provides for Controllers which is akin to Data Fiduciary as provided in the Indian legislative framework. Article 24 of the GDPR creates an obligation on the Controller to take all measures as provided in the GDPR and should be able to demonstrate that processing is being done in such a manner that it does not risk the freedoms and rights of natural persons. |

6. Liability in case of Breach

| 2022 Bill | 2019 Bill | GDPR |

| Section 25 read with Schedule 1 provides for the financial liability up to Rupees Five Crores, if any person fails to comply with the Act or commits a breach of data.

However, the Bill does not provide for any cognizable offence. The following are the liabilities for non-compliance: 1. For Failure of Data Processor or Data Fiduciary to take reasonable security safeguards to prevent personal data breach under sub-section (4) of section 9 of this Act- penalty upto INR 250 Crores can be imposed. 2. Failure to notify the Board and affected Data Principals in the event of a personal data breach, under sub-section (5) of section 9 of this Act- penalty upto INR 200 Crores. 3. Non-fulfilment of additional obligations in relation to Children; under section 10 of this Act – penalty upto INR 200 Crores. 4. Non-fulfilment of additional obligations of Significant Data Fiduciary; under section 11 of this Act – penalty up to INR 150 Crores. 5. Non-compliance with section 16 of this Act- Penalty up to INR 10,000/- 6. Non-compliance with provisions of this Act other than those listed in (1) to (5) and any Rule made thereunder- Penalty up to INR 50 Crores. |

Section 82 provided for imprisonment up to three years or with fine. The offence provided under Section 82 was a cognizable and non-bailable offence.

|

Chapter 8 provides for Remedies, Liabilities and Penalties. The GDPR does not specifically provide for the quantum of fine or punishment. However, as per Article 84, the GDPR gives discretion and power to Member States to lay down the rules on penalties applicable to infringement of this Regulation. Further, such penalties must be proportionate, effective and dissuasive. |

Key Lapses in the 2022 Bill

Narrow applicability of the Bill: As the name of the Bill suggests, the Bill focuses specifically on the digital data of a personal nature. The Bill defines the expression “personal data” under S. 2(13), however, it does not define what constitute a “digital data”. Since, the Bill specifically focuses on digital personal data, it appears that the legislature intended to exclude the applicability of this Bill on personal data stored in a form other than digital. The implication of such exclusion would be that if a breach of personal data which was not stored in a digital form, takes place then no protection could be sought under the 2022 Bill. The title of the Bill and its provisions also leave no scope of interpretation for the Courts to extend the protection to personal data stored in physical form. Further, a cursory perusal of General Data Protection Guidelines (hereinafter referred to as “GDPR”)[2] would entail that GDPR extends to all forms of “personal data”, be it digital or otherwise.

No obligation on data fiduciary for preparing a privacy policy design: Chapter 2 of the 2022 Bill provides for Obligations of a Data Fiduciary. Unlike the 2019 Bill, the new 2022 Bill does not require a data fiduciary to prepare a privacy policy throughout the processing from the point of collection of data to deletion of data. An obligation on data fiduciary for the protection of privacy by design policy has been omitted in the 2022 Bill. This obligation is enshrined under Article 25 of GDPR[3].

No offence, only penalty provided: Section 25 of the 2022 Bill provides for a hefty financial penalty which may extend to Rupees five hundred crores. First Schedule of the Bill provides for penalty. However, the 2022 Bill does not provide for any offence unlike the previous Bill. The 2019 Bill, under Section 82 provided for a punishment with imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or fine which may extend to Rupees Two Lakhs. The legislature has tried to create a deterrence by imposing hefty penalties in crores. However, in case a data fiduciary commits a grave breach but does not hold enough assets which could match the penalty imposed in a given case, then the proceedings would become futile. On the other hand, if imprisonment remains as a primary mode of punishment, then it is likely to create more deterrence in addition to a civil liability.

Hefty penalties likely to deter startups in India: India is now witnessing huge number of startups, and the government policies are also aligned to support startup culture. The revised Bill requires the Data Fiduciary to acquire proper means and process and secure the digital personal data of the Data Principal. However, it is not possible for every startups to put in place all the mechanisms and tools for complying the provisions of the Bill. Further, if any data fiduciary fails to comply with the provisions of the Bill, they shall be subjected to hefty liability extending in crores. This will ultimately impede the growth of startups in India. The penalties should be just, reasonable and proportionate to the quantum of injury caused to the aggrieved. Both civil and criminal liability should be included in the Bill and discretion can be given to the Board or the concerned authority to decide whether fine has to be imposed or criminal liability has to be imputed. The same can be done by including the word “or” in the penal provisions of the Bill and include both civil and criminal liability in a proportionate manner. This will ultimately allow the concerned authority to decide each case on its merits in just, fair and reasonable manner.

Regulatory approval for cross-border flow of digital personal data: In a globalized world, where data collection has become an inalienable part of daily transaction, there is a likelihood of cross-border flow of data outside India. The 2022 Bill is entirely silent on a comprehensive regulatory mechanism for the cross-border flow of digital personal data. In the 2019 Bill, the Data Protection Authority was empowered to monitor the cross-border transfer of data[4] and an obligation was also cast on the data fiduciary to disclose the same[5]. However, the 2022 Bill does not provide for the same and also takes away the powers of Data Protection Board to issue directions for such compliance. In this case, in order to allow proper flow of data outside India, then the same may be regulated with proper guidelines in the Bill itself. Thereafter, if the Bill is passed with these changes, then India’s international obligations would also be fulfilled.

Application of the right to information for a confidential data: Section 12(3) states that the Data Principal shall have the right to obtain from Data Fiduciary about the identities of all Data Fiduciaries with whom the personal data has been shared. However, there may be various cases where the Data Principal may have entered into a non-disclosure agreement with the Data Fiduciary preventing the disclosure of any digital personal data under the right to information. This anomaly should be removed by making the provision more comprehensive and clear.

The right to be forgotten: The Right to be forgotten is an offshoot of the right to privacy which means erasure or deletion of data once the data has become redundant or detrimental to the data principal. Justice Kaul’s opinion in the landmark KS Puttaswamy and Anr. v. Union of India and Ors.[6] reflects a small discussion on the right to be forgotten in the 2019 Bill and GDPR. In a landmark case of Google v. Spain[7], the right to be forgotten is considered as a part and parcel of right to privacy. In India, the right to be forgotten is yet to get a status of fundamental right under Article 21 by the Supreme Court.

The right to be forgotten shall have a significant application in cases where the name of the victims of sexual offences are disclosed. The Supreme Court in Birbal Kumar Nishad v. The State of Chattisgarh[8], ordered that the name of the victims of sexual offences should not be mentioned in proceedings before courts. Further, in Bhupinder Sharma v. State of Himachal Pradesh[9], the Supreme Court held that disclosing the names of victims of sexual offences amounts to an offence under Section 228A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Therefore, in view of these decisions, a victim of sexual offence can seek the erasure or removal of her name, if the same has been disclosed in public domain. The 2022 Bill enshrines the right to be forgotten under Section 13 which shall be subject to reasonable restrictions, and such cases can be properly dealt if the Bill is enacted to this effect.

The problem with Section 13 is that it uses the expression “in accordance with the applicable laws and in such manner as may be prescribed” which is too wide to be considered as a reasonable restriction on a legal right. The latter part of the expression makes the restriction vague and superfluous. In contrast to the Article 17 of GDPR, the 2022 Bill does not cover specific grounds of erasure of data. As per the 2022 Bill, cases where the data principal withdraws the consent cannot be taken as a ground for exercising the right to be forgotten, rather the implication would be that it shall not affect the lawfulness of processing of personal data and the fiduciary shall cease the processing of the personal data. However, the GDPR provides for withdrawal of consent as a ground for invoking the right to be forgotten where there is no other legal ground for processing the data.[10]

Apart from the right of correction or erasure, a duty should be caste upon the Data Principal to intimate or update the Data Fiduciary if there has been a change in personal data. The purpose behind this is that a Data Fiduciary would not have any notice of the change in personal data on its own unless the same is intimated by the Data Fiduciary.

Conclusion

While the enactment of a legislation for data protection still remains to be a pending affair, the 2022 Bill is a welcome step. However, government’s obligations towards protection of personal data would still remain partially unfulfilled. The above-mentioned lapses may be incorporated in the Bill. The GDPR guidelines would still act as a model law to cover various other crevices in the existing 2022 Bill. The High Courts in various states have shown sensitivity towards the protection of personal data of individuals and as such have even applied the right to be forgotten in few cases. As a way forward, the penalties of civil nature should be balanced with criminal liability in order to balance “the protection of personal data” and “processing of personal data”. If the penalties are made proportionate, it will instill confidence in the new startups.

Mohd. Yasin, Intern at S.S. Rana & Co. has assisted in the research of this article.

[1] EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016

[2] EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016, Article 25.

[3] EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016, Article 25.

[4] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Section 49(2)(g)

[5] Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, Section 23(1)(g)

[6] KS Puttaswamy and Anr. v. Union of India and Ors., (2017) 10 SCC 1.

[7] Google Spain SL v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos C-131/12

[8] Birbal Kumar Nishad v. The State of Chattisgarh, SLP (Criminal) No. 7772/2021.

[9] Bhupinder Sharma v. State of Himachal Pradesh, (2003) 8 SCC 551.

[10] EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016, Article 17(1)(b).