India: Trademark Applications Cross 5 Million Mark!!

Adios, IPAB: Government of India officially abolishes the IPAB.

Transactions related to Virtual Currencies- RBI Circular.

Abbreviations as Trademarks- Kerala v. Karnataka! #KSRTC.

TRADE MARKS IN NAMES- NEW ZEALAND IPO REFUSES THE MARK “AUNTY HELEN”.

Dispovan v. Dipcovan – Pharmaceutical Trademark Similarity and likelihood of confusions.

India: Registration of RMPL as a Copyright Society.

India: Trademark Applications Cross 5 Million Mark!!

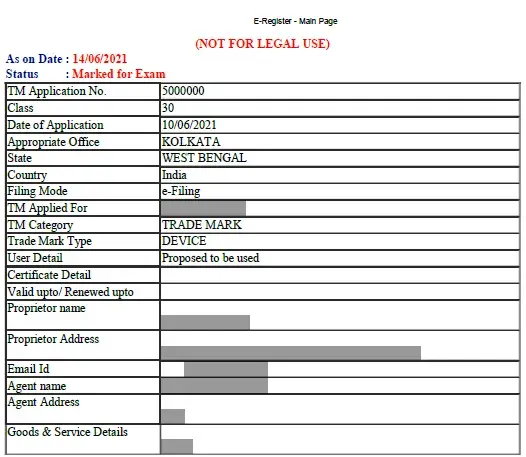

We are thrilled to share that number of Trademark Applications filed in India has crossed the 5 Million mark!! The trademark application numbered as historic 5000000, filed on June 10, 2021 with the Indian Trademark Registry is as under:

Trademark Filing Trends in India

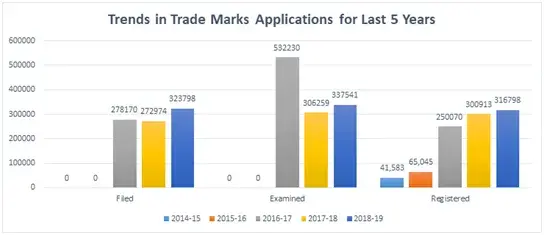

According to the latest Report released by the Indian Trademark Registry, during the period 2018-2019- a total of 3,23,798 trademark applications were filed with the Indian Trademark Registry. The number of trademark applications examined were more than applications filed during this period and pendency in examination of trademark applications was brought down to less than a month. The number of trademark registrations also reflected an increase of 5.3%.

| Year | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

| Filed | 2,10,501 | 2,83,060 | 2,78,170 | 2,72,974 | 3,23,798 |

| Examined | 1,68,026 | 2,67,861 | 5,32,230 | 3,06,259 | 3,37,541 |

| Registered | 41,583 | 65,045 | 2,50,070 | 3,00,913 | 3,16,798 |

| Disposal | 83,652 | 1,16,167 | 2,90,444 | 5,55,777 | 5,19,185 |

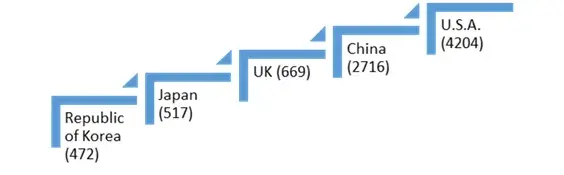

Out of total 323798 trademark applications filed with the Registry; the number of applications filed by foreign applicants during the year 2018-2019 was 13682. The top filers are:

India is drastically transforming and aforesaid figures are a testimony of the same. More and more IP intensive companies and industries are emerging each day and now even Start-ups in India have commenced IP filings and are understanding the substance of IP protection.

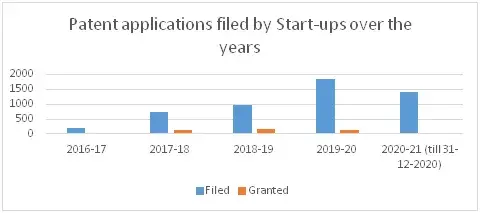

A recent Report released by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), Ministry of Commerce and Industry1, published figures indicating the number of Patents filed by Start-ups over the past few years and the same is illustrated below:

The aforesaid statistics showcase a gradual increase in Patent filings by Start-Ups every year. The Government of India through its various initiatives like the Start-up India Campaign and National IPR Policy has floated schemes and enacted legislative amendments which have made IP filings conducive by entities in India.

Adios, IPAB: Government of India officially abolishes the IPAB.

By Ananyaa Banerjee and Hema Shekhawat

The Government of India (through the Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade – IPR-Estt. Section) has now made available to the public an official notification regarding the dissolution of the IPAB (Intellectual Property Appellate Board)1. The Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs & Trade Marks on its website has uploaded a notification dated June 30, 2021, regarding the said dissolution of the IPAB.

The notification contains a copy of the Gazette of India dated April 22, 2021 (CG-DL-E-22042021-226717), wherein it is stated that pursuant to the Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021, the IPAB stands dissolved w.e.f. from April 04, 2021 [F. No. P-24017/28/2021-IPR-l].

A copy of the said notification can be accessed at https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/News/728_1_Dissolution_notification_0001.pdf.

The said notification finally closes the chapter of the Board and draws the curtain on the esteemed organisation, which was constituted in 2003, under Section 83 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

As noted in our earlier article/update on the subject matter, all proceedings which were pending with the IPAB shall be transferred to the Court before which it would have been filed had this Ordinance been in force on the date of filing of such appeal or application. As such, the functions of the IPAB have been transferred to the appropriate High Courts under various IP Acts.

While the fate of the IPAB has been much debated upon in the last few months, the same stands moot at this point. However, it would be interesting to see how this move pans out, and whether it will lead to an increase in the efficiency of disposal of cases that were pending with the IPAB. For now, we bid adieu to the IPAB and hope that the future remains bright for all stakeholders affected by this.

[1]https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/News/728_1_Dissolution_notification_0001.pdf

Related Posts

India: President Promulgates Ordinance to Abolish IPAB

Justice Manmohan Singh’s tenure extended as IPAB Chairman by Supreme Court

Transactions related to Virtual Currencies- RBI Circular.

By Priya Adlakha and Rima Majumdar

We live in a digital world where everything is available to us at our finger tips, a feat which was unimaginable 12-15 years ago. Devices like modern smartphones literally grants one access to all the knowledge and information available in the world, in a small device which can be stored in pockets! With the onslaught of Covid-19 in 2020, several businesses had to change their traditional way of doing business and embrace digital methods. Newspaper houses were one such business, wherein the business was drastically affected – the old tradition of selling hardcopies of newspapers was put on hold due to COVID-19 and many households had even ceased subscribing to physical newspapers, thus the industry had to strive hard to make the same content available to readers in user friendly e-format.

However, in view of technological enhancements and availability of sharing and streaming options, the contents of these e-newspapers is often not limited for exclusive use of paid subscribers only. Thus, once shared on the internet, the so called paid news becomes available for anyone to access, with very little control over the dissemination. Thus, it is inevitable that a legal issue regarding this would crop up, especially during this time of pandemic wherein the focus on e-media and e-newspapers are higher than ever before.

The publishers of the leading English daily newspapers, the Times of India and Navbharat Times, recently approached the Hon’ble Delhi High Court to restrain instant messaging applications WhatsApp, Telegram, and several administrators of group chats that are run on these apps, from sharing the e-newspapers of Times of India and Navbharat Times, without their (Plaintiff’s) permission, as the same amounted to infringement of the Plaintiffs’ copyright vested in these newspapers.

BRIEF FACTS OF THE CASE

In the case titled Bennett Coleman Co. Ltd. vs. WhatsApp Inc. & Ors.1, the Plaintiff is the publisher of several newspapers of various languages in India, namely The Economic Times, Navbharat Times, Maharastra Times, Sandhya Times etc. Out of all these publications, one newspaper ‘Times of India’ is claimed by the Plaintiff to be India’s most widely circulated English daily which attracts a daily circulation of more than a million copies.

It is the case of the Plaintiff that the news articles in its newspapers are published with indication/credit to the specific named source for instance PTI, Reuters etc. Such news articles / contents published on Plaintiff’s website as well as in its newspapers constitute “the original literary work” within the meaning of “copyright”, thereby being entitled to copyright protection under Section 14 of the Copyright Act, 1957.

The Plaintiff is the exclusive owner of the copyright in its literary work published in its newspaper. Furthermore, the Plaintiff has also started offering its print publication in a digitised format i.e. E-papers, on its website to its paid subscribers i.e. a consumer can subscribe to the E-newspaper on payment of prescribed subscription fee and thereafter the user can readily access any Times Group newspapers.

ALLEGATIONS OF THE PLAINTIFF

The Plaintiff is aggrieved by the unauthorized and illegal circulation/distribution of its e-newspapers by certain users of WhatsApp as well as several other websites that are offering these e-papers for free download, thereby circumventing the subscription model of newspapers in entirety.

The Defendant No. 1, i.e. WhatsApp and Defendant No. 3 i.e. Telegram, are mobile apps which provides its users the ability to form groups for broadcasting messages to a large number of persons at one go. It has been alleged by the Plaintiff that due to access and permissions granted by Defendant Nos.1 and 3 to various users, numerous channels and groups are created by known and unknown administrators / users, wherein various e-papers of the Plaintiff have been illegally uploaded in PDF format on a daily basis without the authorization of the Plaintiff.

In view of the aforesaid, the Plaintiff contended that it being the exclusive owner of the copyright vested in the said literary work, possesses all rights to it in any material form. Hence, the Defendants’ actions of circulating copies of e-newspapers owned by the Plaintiff violated the rights of the Plaintiff.

WHAT WAS HELD BY THE COURT?

The Single Bench comprising of Hon’ble Justice Jayant Nath agreed with the contentions of the Plaintiff, and was satisfied that a prima facie case of infringement was made out against the Defendants. Therefore, an interim injunction was granted, inter alia restraining WhatsApp, Telegram, and certain other individuals from circulating e-newspapers on their respective platforms.

ANALYSIS OF THE ISSUE

One question that arises from the above noted case is that who is liable for copyright infringement in this context – is it the user who is sharing the e-paper or the messaging application which is being used as a medium to share it? This is a question that has the potential to shape the law regarding such a popular and prevalent issue in the long run.

Messaging applications like WhatsApp2 and Telegram have their own internal policies for handling complaints pertaining to infringement of someone’s IP rights, and as a first course of action it is advisable that the party whose IP is being infringed, primarily pursues these channels first and only if they fail to resolve the issue, then a suit for infringement is lodged with the appropriate adjudicatory body.

WhatsApp’s Intellectual Property Policy allows the complainant to request WhatsApp to removes any infringing content it is hosting. However, as per the said policy, the only information WhatsApp is hosting are its users’ account information, including the users’ profile picture, profile name, or status message, if they decide to include them as part of their account information. The policy also states that before submitting an infringement complaint, you may send a message to the user who is suspected of infringing the IP3. Thus, it is evident that WhatsApp’s current policy does not cover information/data/files that are disseminated via messages.

Telegram on the other hand has a list of FAQs on its website wherein it states that all Telegram chats and group chats are private amongst their participants, and Telegram does not process any takedown requests related to them. However, if a user is of the view that any sticker, channel or bot on Telegram is infringing the user’s copyright, a complaint may be submitted for the same. These complaints should only be raised either by the owner of the copyright or an authorized agent of the owner. 4

Furthermore, both of these messaging apps state that information shared by their users through these apps are end-to-end encrypted. Therefore, it may be argued that they are simply an ‘intermediary’ as per Section 2(w) of the Information Technology Act, 2002.

According to the Hon’ble Delhi High Court’s decision in Myspace v. Super Cassettes, FAO(OS) 540/2011 intermediaries (which include online messaging platforms like Telegram/WhatsApp) can claim the ‘safe harbour’ provision available under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act (IT Act) and protect themselves from copyright infringement liability. According to Section 79 and the Rules made thereunder, the intermediary can claim such safe harbour protection from liability, provided it does not have ‘actual knowledge’ of the illegal (here, infringing) content, and does not fail to expeditiously take down such content upon receiving such knowledge. As per the Myspace case, the condition of actual knowledge is satisfied when the specific location where the infringement has occurred is communicated to the intermediary.

Section 79(2) of the IT Act provides that the safe harbour protection shall apply if-

- the function of the intermediary is limited to providing access to a communication system over which information made available by third parties is transmitted or temporarily stored or hosted; or

- the intermediary does not-

- initiate the transmission;

- select the receiver of the transmission; and

iii. select or modify the information contained in the transmission;

- the intermediary observes due diligence while discharging his duties under this Act and also observes such other guidelines as the Central Government may prescribe in this behalf

Furthermore, as per Section 79(3) of the IT Act, the safe harbour protection shall not apply if-

- the intermediary has conspired or abetted or aided or induced, whether by threats or promise or otherwise in the commission of the unlawful act;

- upon receiving actual knowledge, or on being notified by the appropriate Government or its agency that any information, data or communication link residing in or connected to a computer resource controlled by the intermediary is being used to commit the unlawful act, the intermediary fails to expeditiously remove or disable access to that material on that resource without vitiating the evidence in any manner

Also, non-compliance of any of the mandatory due-diligence requirements by an intermediary, as given in the Intermediary Rule, 2021, shall also lead to an intermediary losing its safe harbour protection.5

On February 25, 2021, the Government of India had notified the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.6 The primary objectives of notifying these new rules is to expand the scope of due diligence responsibility and accountability of an intermediary operating or looking to operate in India, as well as to make the establishment and maintenance of Grievance Redressal Mechanisms by an intermediary operating (or looking to operate in India) mandatory.

Rule 3 of the said Rules, inter alia provides that an intermediary, including a social media and significant social media intermediary, shall observe various due diligences while discharging its duties.

One of these due diligences that will be relevant for the purpose of the present case is Rule 3(1)(b)(iv), which provides that “the rules and regulations, privacy policy or user agreement of the intermediary shall inform the user of its computer resource not to host, display, upload, modify, publish, transmit store, update or share any information that infringes any patent, trademark, copyright, or other proprietor rights.”

Since the said Rules were notified, intermediaries such as WhatsApp and Telegram, amongst others, have amended their Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, to be in line with the changes.7

It is also noteworthy to mention that these new Rules also provides in Rule 4(2) that a significant social media intermediary providing services primarily in the nature of messaging shall enable the identification of the first originator of the information on its computer resource as may be required by a judicial order passed by a court of competent jurisdiction or an order passed under section 69 by the Competent Authority as per the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for interception, monitoring and decryption of information) Rules, 2009.

However, an order of this kind shall only be passed for the purposes of prevention, detection, investigation, prosecution or punishment of an offence related to the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, or public order, or of incitement to an offence relating to the above or in relation with rape, sexually explicit material or child sexual abuse material, punishable with imprisonment for a term of not less than five years. Since the present case does not fall under any of the above stated categories, the Plaintiff may not be able to take recourse of this Rule.

CONCLUSION

In the Bennett Coleman case, the interim injunction order does not mention whether the Plaintiff had sent notices to WhatsApp and Telegram, requesting that the infringing material be taken down, before filing the suit.

Be that as it may, in order to prove copyright infringement by both the intermediaries and the admins of the WhatsApp groups and Telegram Channels, the Plaintiff will have to show that:

- The intermediary had knowledge or means of examining the content in question;

- The group/channel admins have control over the infringing content shared on the channels or groups, to see if they generally exercise editorial control (such as removing posts or filtering messaged), or if they permit unlawful activity despite knowledge of the same;

- Non-compliance by the intermediary of the latest Intermediary Rules, thereby stripping it of its ‘safe harbour’ protection.

The issue pertaining to liability of an intermediary is quite young in India. Perhaps this is why the Hon’ble Delhi High Court in the Myspace case, referred to several judgments of foreign courts, to come to the decisions about the liability of an intermediary for copyright infringement. It is noteworthy to refer to the case of Religious Technology Center Vs. Netcom Online Communication Services Inc. 907 F. Supp. 1361 (1995), which was decided before the DMCA came into effect. In the said case, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California held that “where the infringing subscriber is clearly directly liable for infringement, imputation of liability on countless service providers whose role is nothing more than setting up and operating systems which necessary for the functioning of the Internet is illogical. It was further held that finding intermediaries responsible for the act of others, which cannot be deterred would be impractical and theoretically impossible especially given that “Billions of bits of data flow through the Internet and are necessarily stored on servers throughout the network and it is thus practically impossible to screen out infringing bits from non- infringing bits.”

A similar case of this kind concerning copyright infringement was filed by Dainik Jagaran last year in 2020, against Telegram and unnamed Defendants operating certain Telegram channels, which allegedly circulate versions of the Plaintiff’s newspaper through PDF. You can read our analysis of the said case click here to learn more.

The Bennett Coleman case is now listed for further proceedings on August 18, 2021. It should be interesting to see what defence the Defendants claim in this suit then.

[1] CS (COMM) 232/2021

[3] ibid

[5] Rule 7 of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021

[6] https://www.meity.gov.in/content/notification-dated-25th-february-2021-gsr-139e-information-technology-intermediary

[7] https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/7-social-media-giants-comply-with-new-it-rules-twitter-dithers-259910

Abbreviations as Trademarks- Kerala v. Karnataka! #KSRTC..

By Vikrant Rana and Pranit Biswas

Abbreviations and trademarking thereof is common in many countries of the world, including in India. Abbreviations are powerful brand markers, which oftentimes are much more famous than the name or brand in question! Indeed, one can say that famous Indian abbreviations such as the BCCI, UGC, RAW, FICCI, NOIDA, AIIMS, etc. are more popular than their full forms! Many would even be hard-pressed to even provide the full-forms of such famous abbreviations.

However, one of the worst things that can occur with usage of abbreviations from a trade mark perspective is that when two different entities have been using the same abbreviation, and both acquire enviable goodwill and reputation. Such a recipe for disaster can be grossly exacerbated by the unfortunate circumstance wherein both entities are involved in the same industry/business or deal in similar/identical goods and services. Another factor which would further complicate the situation is that both entities in question have been using the said abbreviation for a very long time and one does not have significant primacy over the other, in terms of prior adoption. While the above situation and amalgamation of circumstances appear to belong to the realm of unreal, such situations have in fact occurred in the past, with the case of WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature) v. WWF (World Wrestling Federation) being one of the most noteworthy of such cases in the world – which lead to the famed World Wrestling Federation (WWF) rebranding itself to World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), despite it having significant independent goodwill and reputation in the abbreviation.

Such a situation has also recently unfolded in India with much media fanfare surrounding it – specifically regarding the abbreviation KSRTC. For people living in the states of Karnataka and Kerala, the said abbreviation denotes two very different things – the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation for Kerala; and Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation for Karnataka. Thus, it was inevitable that a dispute would arise at some point of time.

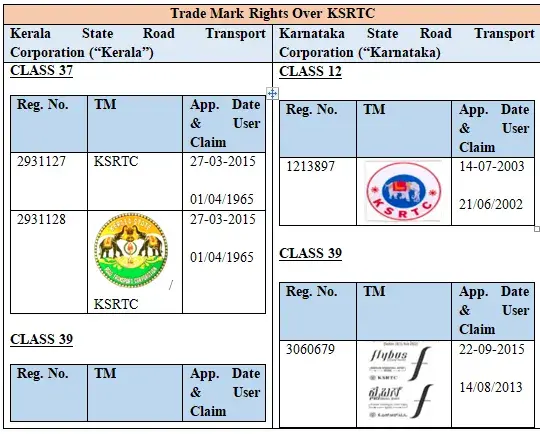

KSRTC V. KSRTC! WHAT’S BEEN REPORTED

It has been recently been reported by many leading news outlets in India that a trade mark dispute has been going on between the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (“Kerala”) and Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (“Karnataka) regarding usage of the abbreviation KSRTC, which is the short-form/abbreviation for the full names of both organizations. It has been reported that a dispute regarding the trademark over the abbreviation KSRTC has been going on for over the last 7 years. The dispute purportedly when Karnataka filed an application for the mark KSRTC and apparently called upon Kerala to not use the acronym KSRTC further[1]. Both corporations had been using the said acronym for decades, thus cementing their reputation and goodwill in their respective states. Kerala purportedly commenced use of the acronym/abbreviation in 1965 whereas Karnataka commenced use of the same in 1974. In light of this background, Kerala has recently claimed that the Trade Marks Registry in its ‘verdict’ has given them the right to use the abbreviation KSRTC, the emblem as well as the nickname ‘Anavandi’, In response, Karnataka has claimed that it has not received any such Order and is exploring legal options[2]. However, it has been further reported that both Kerala and Karnataka have valid and subsisting trade mark rights in the abbreviation KSRTC and the trade mark rectifications filed by Kerala against Karnataka’s registrations before the IPAB (now deemed defunct/abolished) are still pending[3].

IP RIGHTS INVOLVED IN THE DISPUTE

In view of the above myriad of claims and allegations and justifications, it is important to ascertain the various IP rights involved in this matter:

From the above trade marks, it is evident that Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (“Kerala”) prima facie has the upper-hand from a trade mark perspective, as well as the fact that their claimed use stretches back to 1965, i.e. date of conversion of the erstwhile Travancore State Transport Department to the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation in 1965[4]. Further, it is also pertinent to note that both entities have co-existing registrations over the KSRTC abbreviation/mark in class 37, although Kerala possess a word-mark registration as opposed to Karnataka’s device mark in the said class. However, KERALA had filed rectification against KARNATAKA’S aforementioned trade mark registration no. 1213897 for the mark with the IPAB Chennai, vide ORA/166/2015/TM/CH/5533 in 2015. It has been reported that the rectification is still pending and now the same has been transferred to the High Court due to the dissolution of the IPAB.

PRIORITY OF RIGHTS

As both entities have been using the abbreviation KSRTC for a very long time and both have valid and subsisting registrations over the said mark, one of the most important facts of such cases would be priority of use.

It has been reported that Kerala trumps Karnataka in this respect, as the use of the abbreviation by Kerala dates back to 1965 whereas Karnataka can establish its use from the mid-1970s only.

However, while the rectification is still ongoing, and there prima facie there does not appear to be any further legal escalation, it is important to explore two very relevant questions brought up by this dispute –

- Can abbreviations be trademarked?

- Can such marks co-exist?

Can such Abbreviations be registered as trademarks?

There is no specific prohibition in the Trade Marks Act, 1999, which restricts such trade marks. Further, in case the abbreviation in question has acquired a secondary meaning, i.e. immense reputation and goodwill, then the chances of obtaining such registration would indeed be fair. In fact, the Registry has indeed registered many abbreviations in the past, such as VIT and M&M – please refer to our earlier article on this topic at https://ssrana.in/articles/india-conflict-and-ruling-on-bonafide-use-of-acronym-as-trademark/.

However, registrability aside, issues would undoubtedly arise if the said acronym/abbreviation is being used to similar/identical services – as was the case in the KSRTC matter.

Can such marks co-exist?

Marks such as the one in question, if it clears the hurdles of Sections 9 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 can indeed co-exist, and the same is indeed provided for in the statute itself, in the form of Section 12:

- Registration in the case of honest concurrent use, etc.—In the case of honest concurrent use or of other special circumstances which in the opinion of the Registrar, make it proper so to do, he may permit the registration by more than one proprietor of the trade marks which are identical or similar (whether any such trade mark is already registered or not) in respect of the same or similar goods or services, subject to such conditions and limitations, if any, as the Registrar may think fit to impose.

As such, in view of their long, continuous, uninterrupted and bonafide use, both parties may have valid rights over the abbreviation.

Secondary Meaning- Abbreviations as Trademarks

Coupled with the above factum, it is pertinent to shed some much deserved spotlight on the highly debated concept of secondary meaning. While the mark/abbreviation KSRTC in itself may lack distinctiveness, it can be said that the said abbreviation has acquired a secondary meaning within Kerala and Karnataka. Considering the length and scale of use, and the nature of services, it is likely that the abbreviation KSRTC denotes very different things, i.e. the respective states’ buses/ corporation, to citizens of the two states.

As such, the mark may be said to have a secondary meaning at least within the confines of the respective states.

ACCEPTABLE LEGAL COMPROMISE? STAY WITHIN YOUR LIMITS!

The present dispute regarding the KSRTC raises a question which goes beyond the question of registrability of marks. In the present case, both Kerala and Karnataka have valid and subsisting rights over the said term/mark and the mark can be said to have acquired distinctiveness and secondary meaning in their respective states. Both organizations have been using the mark for decades, seemingly unopposed till 2015. Both organizations have registered their marks with the Trade Marks Registry, and the latter user, i.e. Karnataka, can be said to be honest and bonafide user of the mark.

As such, in these cases, an acceptable compromise may be to register such marks with strict disclaimers which bind the usage to a certain geographical territory. The Registry for a long time has been known to grant registrations with disclaimers regarding location – for example registering marks with the disclaimer that the same shall be solely for services pertaining to the state of Karnataka/ Kerala. Thus, this solution would not only permit entities such as Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (“Kerala”) and Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (“Karnataka) to use and register their trade marks, but also prevent undue monopolization of an abbreviation which may be of use to others also. However, the above solution may not be practical in this particular case, considering that Kerala and Karnataka are neighbouring states and buses of each organization ply in either state. Thus, another solution in such cases would be a compromise wherein one organization uses a highly stylized logo to differentiate its mark from the others’, or uses dots/periods between the alphabets, i.e. K.S.R.T.C.

Additionally, it is noteworthy in this matter that the final disposal of the trade mark rectification/cancellation action in favour of Kerala would not per se bar Karnataka from using the KSRTC abbreviation/mark, as has been claimed in the media. The actual usage of the mark by one party can only be addressed if a lawsuit is filed and they are restrained by a court from using the mark.

[1] KSRTC vs KSRTC: All you need to know about the Karnataka-Kerala trademark row; Deccan Herald – https://www.deccanherald.com/state/ksrtc-vs-ksrtc-all-you-need-to-know-about-the-karnataka-kerala-trademark-row-994063.html

[2] Two states, one brand: how Kerala won battle against Karnataka for KSRTC trademark; Indian Express – https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/how-kerala-won-battle-for-ksrtc-trademark-7344760/

[3]‘Reports that Karnataka cannot use KSRTC factually incorrect’; The Hindu – https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/reports-that-karnataka-cannot-use-ksrtc-factually-incorrect/article34730027.ece

[4] History of Kerala State Road Transport Corporation, https://www.keralartc.com/about-us/history#:~:text=1965.,made%20expeditiously%20by%20the%20Corporation.

Related Posts

India: ‘Be U’ Bengaluru Becomes India’s First City to Have Its Own Logo

TRADE MARKS IN NAMES- NEW ZEALAND IPO REFUSES THE MARK “AUNTY HELEN”.

By Hema Shekhawat and Pranit Biswas

Trademarking a name is not an unusual occurrence. Many IP Offices over the world allow registration of trade marks in names, including in India. However, a line is indeed drawn when one attempts to trade mark the name of a third party – especially when the name in question is a famous one, that too of a living person as opposed to someone who has long left this world.

In a recent intriguing trade mark opposition case before the Assistant Commissioner of the Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand[1], the venerable Mrs. Helen Clark, former Prime Minister of New Zealand (1999-2008) was constrained to file opposition against one Mr. James Craig Benson’s application nos. 1102116 and 1102309 for the mark AUNTY HELEN. Mrs. Clark is famously and affectionately known as Aunty Helen in New Zealand as well as internationally. The Applicant, Mr. Benson, purportedly decided to adopt the mark AUNTY HELEN as Mrs. Clark apparently once during an interview stated that she does not intend to use or register the said nickname as a trade mark. In fact, a key defence relied upon by Mr. Benson was that Mrs. Clark does not and has not in the past used the term AUNTY HELEN commercially or as a trademark. Incidentally, or perhaps not, Mr. Benson had also filed an application for the mark JACINDARELLA (application no. 1109244) in classes 25, 35, 36, 39, 41 and 45. The term “Jacindarella” was used by the New Zealand media to refer to Ms. Jacinda Ardern (the current Prime Minister of New Zealand), which was a clever combination of the words JACINDA and CINDERELLA.

Contentions Of The Opponent – Mrs. Helen Clark

The opponent had relied on the below grounds in the opposition as enumerated under the Trade Marks Act 2002 of New Zealand:

| Relevant Sections | Objections of the Opponent |

| Section 17(1)(a) | Use of AUNTY HELEN by Mr Benson is likely to cause deception or confusion given the reputation there is for the nickname AUNTY HELEN as a reference to Ms Clark. |

| Section 17(1)(b) | Use of AUNTY HELEN by Mr Benson will be likely to mislead or deceive and will amount to false or misleading representation giving rise to a breach of sections 9 and 13 of the Fair Trading Act 1986 and will also amount to passing off. |

| Section 17(2) | the application for registration of AUNTY HELEN was made in bad faith |

| Section 25(1)(c) | Ms Clark’s AUNTY HELEN nickname is a trade mark, that is well known, and use of AUNTY HELEN by Mr Benson would prejudice the interests of Ms Clark. |

| Section 32(1) | Mr Benson is not entitled to claim to be the owner of the AUNTY HELEN trade mark |

The Opponent had also submitted substantial evidence, including many news articles referring to Mrs. Clark as AUNTY HELEN, as well as details of the Applicant’s/ Mr. Benson’s other trade mark application for the mark JACINDARELLA.

The Applicant’s (Mr. Benson’s) rebuttals

Mr. Benson in his counterstatement had contended that:

- Clark is nether at present, nor in the past, used the term AUNTY HELEN in commerce, including the goods and services falling under his applications.

- Only third parties refer to Mrs. Clark as AUNTY HELEN and she herself does not refer to herself as such.

- The said mark is not distinctive with respect to any goods or services of Mrs. Clark.

- Clark has not made any assertion regarding ownership of the said mark.

- The said mark is capable of distinguishing the goods and services of the Applicant from those of others.

- His conduct in filing the applications does not fall below the standards of acceptable commercial behaviour.

Mr. Benson had also submitted evidence to substantiate his claims and positions, including that he had reserved the company name ‘Aunty Helen Publishing Limited’ as well as several domain names comprising of the term AUNTY HELEN.

Interestingly, Mr. Benson had also submitted that for relying on section 17(1)(a) as a ground of opposition, the opponent needs to first establish there is certain reputation attached to the trade mark before the question of likelihood of confusion or deception can be considered. The Applicant/Mr. Benson had also raised the question of censorship – that the oppositions are an attempt to limit his right to freedom of expression, and hence amounts to quasi-censorship. Although, this was rebutted by the argument by the Opponent that a successful opposition would not impact the right to freedom of expression. The Assistant Commissioner of IPONZ also concurred that opposition would not prevent the Applicant from selling clothing, publishing or expressing his opinion. Another interesting contention of the Applicant was that allowing the opposition would have the effect of granting the Opponent a monopoly right in her ‘image’ or personality, which is not a recognised right in New Zealand.

The Assistant Commissioner’s Observations

Upon analysing the submissions and evidence submitted by both parties, which included substantial evidence by the Opponent, the Assistant Commissioner of IPONZ deliberated upon the below questions:

| Question/ Issue | Assistant Commissioner’s Deliberations/ Observations/ Rulings |

| Does AUNTY HELEN need to be used as a trade mark by Ms Clark? | No. The ambit of Section 17(1)(a) cannot be limited to trade mark reputation. The section is broad enough to encompass likelihood of confusion if there is a reputation in the AUNTY HELEN nickname. It does not matter what ‘species’ of reputation is under consideration. The Assistant Commissioner also noted that when a trade mark encompasses a name, written consent from the said named person may be required. |

| How is the likelihood of confusion or deception to be approached in this case? | Similar to how one would look at it from a trade mark perspective, with minor variations, considering that the word/term in question is a nickname.

In this case, for there to be a likelihood of confusion, there must be consumers who are aware of the reputation in the nickname – which they do. |

| What amounts to reputation? | The Opponent need not be trading in goods or services. Reputation is something which has a low threshold, and it can be equivalent to neutral terms like “awareness”, “cognisance” or “knowledge”. |

| Is there a reputation for the nickname AUNTY HELEN in New Zealand? | Yes, and the same was also admitted by the Applicant. Ms. Helen Clark is a well-known person in New Zealand and is indeed referred to as AUNTY HELEN by many third parties and is known by the said nickname to a significant portion of the general public. |

| What amounts to likely confusion or deception? | The mark in question has to be looked at from the perspective of how it will be presented to the consumer. The overall impression has to be considered (including the nature of goods, method of sale, etc.).

In this regard, the Assistant Commissioner considered both sides’ arguments and also relied upon the IPONZ guidelines on suggestions of endorsement or licence, specifically regarding when objections under section 17(1)(a) may be raised because of concerns over requirements of consent, sponsorship, etc. The guidelines and the specific excerpts mentioned in the Assistant Commissioner’s order also include the requirement for consent when the mark applied for is the name of famous persons or organisations.

The Assistant Commissioner considered this aspect from both parties’ point of views and even acknowledged that the inclusion of a well-known person’s name in a trade mark will not always lead to likely confusion of consumer. It is pertinent to note here that the IPONZ had in fact not raised any objection under Section 17(1)(a) while examining the AUNTY HELEN trade mark applications. The Assistant Commissioner was in fact surprised to note that no such objection was raised in the examination stage.

However, the Assistant Commissioner digressed from the Trade Marks Examiner’s opinion, and was of the opinion that an Objection could have been raised, as was done for the application for the mark JACINDARELLA. Taking into consideration many factors as well as examples, the Assistant Commissioner held that the Applicant has not been able to establish that the use of AUNTY HELEN on the goods and services of the applications is not reasonably likely to cause deception or confusion. |

| Element of Bad Faith u/s 17(2) | The Assistant Commissioner relied on a plethora of case laws and noted that bad faith is a serious allegation, which has to be supported by evidence. The Assistant Commissioner took note of various contentions made by the Applicant himself (including knowledge of Ms. Clark, the nickname AUNTY HELEN associated with her, application for the mark JACINDARELLA) and noted that a person making such an application would understand that the use of the term AUNTY HELEN is likely to imply some degree of sponsorship or endorsement. The Assistant Commissioner also noted the fact that the specification of services under classes 36, 39 and 45 indicated that the mark AUNTY HELEN was intended to be used in connection with services related to politics, and accordingly take commercial advantage of the nickname. Although, the said classes were later amended/deleted by the Applicant. Accordingly, the Assistant Commissioner made a finding of bad faith and held the said ground of opposition to be in favour of the Opponent. |

As the Assistant Commissioner held in favour of the Opponent with respect to the grounds of opposition under Sections 17(1) and (2), there was no need to make findings regarding other ancillary grounds. As such, the application nos. 1102116 and 1102309 for the mark AUNTY HELEN were refused registration. The Assistant Commissioner also decreed costs amounting to $6,650 (New Zealand Dollars).

THE TAKEAWAY

The above administrative decision by the Assistant Commissioner of the IPONZ is a fascinating case study about the various considerations one must keep in mind when dealing with trade marks which comprise of famous names. In fact, New Zealand being a common law country, such a decision would have value beyond the borders of the remote island nation in the Southern Hemisphere, and may be of precedential value in other common law countries as well, including India.

THIRD PARTY APPLICATIONS FOR FAMOUS NAMES IN INDIA

This case from New Zealand also draws attention to another prominent common law country wherein there is a lot of potential of such trade mark misuse, namely India. India has innumerable celebrities – from sportspersons to politicians to Bollywood stars, whose names one might one to exploit as a trade mark.

In India, there is no specific provision under the Trade Marks Act, 1999, which prohibits registration of names as trade marks. As such, many celebrities, ranging from Sachin Tendulkar to Kajol, have obtained trade mark registrations for their names. A name can be registered, provided that it is capable of distinguishing goods and services of the Applicant from those of others.

However, the question is, can a person/ third party successfully obtain registration over a trade mark which is the name of a famous person? The Trade Marks Act, 1999 does bar such applications under Section 14, which is reproduced below:

- Use of names and representations of living persons or persons recently dead.—

Where an application is made for the registration of a trade mark which falsely suggests a connection with any living person, or a person whose death took place within twenty years prior to the date of application for registration of the trade mark, the Registrar may, before he proceeds with the application, require the applicant to furnish him with the consent in writing of such living person or, as the case may be, of the legal representative of the deceased person to the connection appearing on the trade mark, and may refuse to proceed with the application unless the applicant furnishes the Registrar with such consent.

As such, one would imagine that the Registry would prohibit a third party from registering famous names such as that of our very own incumbent Prime Minister of India, Shri Narendra Modi. In fact, for example, an application no. 2955410 for the trade mark  was filed by one Mr. Chahuhan Rameshbhai Kanjibhai (Trading As : NAMO GROUP FOUNDATION) in class 45 on May 05, 2015. In this regard, the Registry had issued an Examination Report dated June 17, 2016, wherein it had directed the Applicant to provide a consent letter of the person appearing in the mark – which in this case would have been the Prime Minister himself! As no reply to the said office action was filed, the mark was deemed as abandoned. Thus, it is likely that the Indian Trade Marks Registry would object to registration of such trade marks.

was filed by one Mr. Chahuhan Rameshbhai Kanjibhai (Trading As : NAMO GROUP FOUNDATION) in class 45 on May 05, 2015. In this regard, the Registry had issued an Examination Report dated June 17, 2016, wherein it had directed the Applicant to provide a consent letter of the person appearing in the mark – which in this case would have been the Prime Minister himself! As no reply to the said office action was filed, the mark was deemed as abandoned. Thus, it is likely that the Indian Trade Marks Registry would object to registration of such trade marks.

However, it would be interesting to see whether the Registry would refuse registration to marks such as NaMo (a moniker by which Prime Minister Modi is referred to by a rather large strata of society) or RaGa (a similar moniker and shortened version of the politician Mr. Rahul Gandhi).

Also read Prime ministers’ brand Rise of trademark filing trend for ‘’NaMo’’ related trade mark in India

[1] James Craig Benson v Helen Elizabeth Clark [2021] NZIPOTM 6 – http://www.nzlii.org/nz/cases/NZIPOTM/2021/6.html

Dispovan v. Dipcovan – Pharmaceutical Trademark Similarity and likelihood of confusions.

By Lucy Rana and Pranit Biswas

India has a thriving pharmaceutical industry, which is grown in leaps and bounds in the last few years. Its importance to the world as a whole cannot be overstated – it is for good reason many people refer to India as the World’s Pharmacy or consider it to be the world’s greatest vaccine producer. The latter has become very evident in the last few months, as the rate of production of COVID-19 vaccines in India has surpassed all global expectations. Leading private sector companies like the Serum Institute and Bharat Biotech are now on the tips of everyone’s tongues globally. It was in fact recently reported by the Indian Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF) that the Indian pharmaceutical sector supplies over 50% of the global demand for vaccines. It has also been forecasted that the Indian pharmaceutical sector would reach a staggering value of around 120-130 billion USD by 2030[1]. While the sector is indeed booming and is burgeoning with possibilities of reaching greater heights than ever. With the increased importance and global role of the Indian pharmaceutical sector, attention would inevitably be directed to the status of intellectual property, especially trademark law and general branding practices, in India. In this regard, a dispute regarding two similar-sounding pharmaceutical names/trademarks, i.e. Dispovan v. Dipcovan was reported in the Indian media. This piece will analyze the said dispute, especially with the eyes of the earlier important judicial precedents regarding the subject matter.

Pharmaceutical Trademark Similarity

DISPOVAN V. DIPCOVAN

It has been recently widely reported in many leading Indian Dailies that there was a trademark dispute between the government-run organization Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO)/ Vanguard Diagnostics and Hindustan Syringes and Medical Devices (HMD), which is the maker of the quite famous syringe brand DISPOVAN.

Dispovan is quite a famous brand of single-use disposable syringes, which many readers may in fact have encountered during vaccination and other injection-based medical procedures. HMD was in fact reportedly in receipt of an order from the Indian Government for the supply of 265 million auto disposable syringes[2]. HMD is also the owner of the below trademark registration for the DISPOVAN mark in India:

| Reg. No. | Trade Mark | Reg. Date | Class | Status |

| 456928 | 15-July-1986 | 10 | Registered and renewed upto 15-July-2027. |

Whereas, DRDO is India’s premier government agency for a wide variety of research and development, including but not limited to for advanced weaponry such as missiles to medical components. It has in fact been actively aiding in the fight against COVID-19 and has reportedly recently released an Anti-Covid drug[3].

DRDO, in collaboration with the indigenous diagnostic company Vanguard Diagnostics, had recently developed and launched a COVID antibody detection kit, under the brand name DIPCOVAN, purportedly with the below packaging4:

Vanguard Diagnostics had also filed the below application for the aforesaid brand name:

| App. No. | Trade Mark | App. Date | Class | Status |

| 4589480 | DIPCOVAN | 30-July-2020 | 10 | Opposed (by HMD) |

Due to the prima facie similarity between the marks DISPOVAN and DIPCOVAN, and considering that they both fall under class 10 of the Nice Classification, it seems inevitable that a trademark dispute would arise regarding the same, which it reportedly did. The aforesaid application for DIPCOVAN was indeed opposed by HMD (vide opposition no. 1075355 on November 26, 2020). Further, reports on various news outlets suggest that HMD may have also approached DRDO/ Vanguard to urge them to adopt a different name for their product, likely by sending a Cease & Desist Letter5.

MATTER RESOLVED

It has now been reported that the matter between HMD and DRDO/ Vanguard has been amicably resolved, leading to the resultant withdrawal of the trademark application no. 4589480 for the mark DIPCOVAN, vide a letter of withdrawal which can be accessed from the Trade Marks Registry’s website at https://ipindiaonline.gov.in/eregister/showdocument.aspx?DOCUMENT_NO=WFlaW1xdKS4qLCorMClYWVpbXF0=.

TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT/ PASSING-OFF IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL SECTOR – TRENDS

There have been a plethora of cases over the years in India, which have dealt with trademark infringement and passing-off in the field of pharmaceuticals. One commonality in this ample body of jurisprudence is that the benchmark of the likelihood of confusion in cases involving pharmaceuticals has to be minimum or even bare minimum. This principle was elaborated in great detail by the Supreme Court of India in the landmark case of Cadila Health care Ltd. v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd.6 The fact that the threshold of the likelihood of confusion is quite low for such marks and cases can also be seen from the recent case of Mankind Pharma Limited v. Novakind BioSciences Private Limited, wherein the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi had granted an ex-parte ad-interim injunction in favor of the Plaintiff (Mankind), restraining the defendant from, inter alia, manufacturing and selling any pharmaceutical product bearing the suffice ‘KIND’. In this case, the Plaintiff was the proprietor of the well-known trademark MANKIND and various other marks with the suffix KIND, whereas the defendant was using the mark DEFZAKIND for its pharmaceutical preparation/medicine.

Thus, in the present case of DISPOVAN V. DIPCOVAN, it is quite likely that had the matter gone to Court, the Court would have ruled in favor of HMD.

Related Posts

Infringement and Passing Off in Pharmaceutical Trademarks to be Minimum

A Candid Win for Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Ltd. in Trademark Infringement Suit

[1] Indian Pharmaceuticals Industry Analysis: https://www.ibef.org/industry/indian-pharmaceuticals-industry-analysis-presentation#:~:text=India’s%20drugs%20and%20pharmaceuticals%20exports,US%24%2025%20billion%20by%202025.

[2] Covid-19 vaccination: HMD bags govt order for supply of 265 million auto disposable syringes, Business Today: https://www.businesstoday.in/coronavirus/covid-19-vaccination-hmd-bags-govt-order-265-million-auto-disposable-syringe/story/433558.html

[3] DRDO’s anti-Covid drug 2-DG: Second batch of 10,000 packets to be released tomorrow, Live Mint: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/drdos-anti-covid-drug-2-dg-second-batch-of-10-000-packets-to-be-released-tomorrow-11622037866917.html

[4] DRDO unit develops antibody detection-based kit ‘Dipcovan’, Live Mint: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/drdo-unit-develops-antibody-detection-based-kit-dipcovan-11621605550195.html

[5] Dispovan owner to urge DRDO for new name of Covid anti-body kit: Punjab News Express – https://www.punjabnewsexpress.com/health/news/dispovan-owner-to-urge-drdo-for-new-name-of-covid-anti-body-kit-138375 ; ‘DRDO Dipcovan brand too similar to Dispovan’ — Syringe maker warns govt agency of legal action, ThePrint.in – https://theprint.in/health/drdo-dipcovan-brand-too-similar-to-dispovan-syringe-maker-warns-govt-agency-of-legal-action/663425/

[6] Cadila Health care Ltd. v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd., (2001) 5 SCC 73

India: Registration of RMPL as a Copyright Society.

By Hema Shekhawat and Shilpi Sharan

The Recorded Music Performance Limited (RMPL) is an organization that works to manage and license the public performance and radio broadcasting rights of its member companies. On May 22, 2018, RMPL had applied to the Registrar of Copyrights for its registration as a ‘Copyright Society’ that would function in the copyright business of ‘sound recording works’.

Read Recorded Music Performance Limited applies for registration as Copyright Society

On June 18 2021, the Registrar of Copyrights has granted due registration to RMPL as a Copyright Society under sub-section (3) of Section 33 of the Copyright Act, 1957 with the Registration No. CS/03/SOUNDRECORDING/18. This registration allows RMPL to commence their work of licensing and managing copyrights.[1].

Under the Copyright Act, a copyright society functions as a collective management firm, wherein it manages the interest of copyright holders and issues/grants license for such works. Copyright Societies are helpful and beneficial to individual authors and copyright holders as they provide an organizational structure for legal exploitation of copyright and for collecting royalties.

The RMPL has specified that the licenses issued by it are conditional, non-exclusive and can only be exercised for a limited period.

Although Section 33(3) of the Act states that ordinarily only one copyright society shall be registered to do business in respect of the same class of works, RMPL India is the second Copyright Society to be registered in the class of ‘sound recordings work. The first, was the Phonographic Performance Limited India which was registered as a copyright society from 1996 till May, 2014. The application for re-registration of Phonographic Performance Limited is pending before the Government.[2]. It remains to be seen whether this application would be affected by the registration of RMPL as a Copyright Society or not?,

Related Posts

India: Recorded Music Performance Limited applies for registration as a Copyright Society

India: Re-Registration of IPRS as Copyright Society

[1] https://copyright.gov.in/Documents/PublicNotice51.pdf

[2] https://www.pplindia.org/s/what-is-ppl