WHATSAPP GROUP ADMINS OFF THE HOOK FOR POSTS/COMMENTS BY OTHER GROUP MEMBERS.

It is comically undeniable that as a reflex people skip the odious rules, terms and conditions before signing up on any online platform, and only seek them out when either facing glitches or the said term & conditions become hot topics for national news.

It is comically undeniable that as a reflex people skip the odious rules, terms and conditions before signing up on any online platform, and only seek them out when either facing glitches or the said term & conditions become hot topics for national news.

Ludo- A Game of Chance or Skill- Bombay High Court.

The board game, LUDO, is the perennial nostalgic favourite from everyone’s childhood, having historic roots dating back to depictions and iterations of it in the cave paintings of Ajanta-Ellora, as well as in the Mahabharatha.

The board game, LUDO, is the perennial nostalgic favourite from everyone’s childhood, having historic roots dating back to depictions and iterations of it in the cave paintings of Ajanta-Ellora, as well as in the Mahabharatha.

THE RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN.

The very idea of privacy has seen been challenged by the widespread use of the internet. Privacy as such is very hard to enforce, as compared to pre-internet and social media times. Accordingly, the debate regarding the right to be forgotten has been raging on for a very long time.

The very idea of privacy has seen been challenged by the widespread use of the internet. Privacy as such is very hard to enforce, as compared to pre-internet and social media times. Accordingly, the debate regarding the right to be forgotten has been raging on for a very long time.

COMPENSATION FOR HOME-MAKERS OF THE NATION

Recently, the Supreme Court in the case of Kriti v/s Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. opined that while calculating the notional income in motor vehicle accidents, the deceased and non-earning members including homemakers should also be taken into consideration to arrive to a fair and just compensation.

Recently, the Supreme Court in the case of Kriti v/s Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. opined that while calculating the notional income in motor vehicle accidents, the deceased and non-earning members including homemakers should also be taken into consideration to arrive to a fair and just compensation.

WHATSAPP GROUP ADMINS OFF THE HOOK FOR POSTS/COMMENTS BY OTHER GROUP MEMBERS.

By Ananyaa Banerjee and Isha Tiwari

It is comically undeniable that as a reflex people skip the odious rules, terms and conditions before signing up on any online platform, and only seek them out when either facing glitches or the said term & conditions become hot topics for national news. WhatsApp has once again caught itself in the whirlwind of a legal battle. The infamous saga of ‘forwarded messages’ had clutched this country in mass violence and unrest with the dissemination of fake news and to curb the same, WhatsApp had revised its forwarding limits to a message by a user from forwarding any message up to 20 times to forward it to only five chats at once. The idea ever remains the same, to teach use with careful consideration, as the messaging giant can only do so much to monitor the content without encroaching on user’s privacy.

Now, the Hon’ble Bombay High Court has ruled that an administrator of a WhatsApp group, cannot legally be held liable for any offensive post by other members of the group. The Hon’ble Court also opined that the administrator has restricted powers of adding or deleting members to the group, and he is not conferred with the power to regulate or censor the action of the other group members.

BRIEF BACKGROUND

As per the ‘Best Practices for Use of WhatsApp’, the responsibilities of a group admin are fairly laid out, i.e. (1) creating a group; and (2) controlling the ability of sharing messages by other admins/group members[1]. Thus, the issue before the Hon’ble Court was whether a group administrator can be held vicariously liable for the content posted by another group member under Sections 354-A(1)(iv) (Sexual Harassment), 509 (Word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman) and 107 (Abetment of a thing) of the Indian Penal Code and Section 67 (Punishment for publishing or transmitting obscene material in electronic form) of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

In the present case, the Applicant, Mr. Kishor Tarone, was the administrator of a WhatsApp group who was accused by a group member (Applicant No. 2) that the Applicant did not take necessary proactive measures against another accused member for insulting her, such as by excluding the accused member from the group and requesting for an apology thereof. Instead, the Applicant had cited ‘helplessness’. In order to seek justice, the Non-Applicant No. 2 filed an FIR against the accused member and the Applicant, and after the investigation a charge-sheet was drawn against the Applicant as well based on the abovementioned offences. Subsequently, the Applicant filed the present application seeking quashing of the charge-sheet so filed against him.

ORDER IN THE CASE

A. Section 354(a)(1)(iv) of IPC

In the present situation, the administrator of a WhatsApp group’s refusal to exclude a member or to demand an apology from a member who made the offensive comment does not equate to making sexually coloured remarks. Even if the allegations contained in the First Information Report and the evidence introduced in the charge-sheet are believed to be accurate, the ingredients of the offence under section 354-A(1)(iv) of the Indian Penal Code are not satisfied. The wording of Indian Penal Code section 354-A(1)(iv) does not incorporate vicarious liability, nor can it be said that the Legislature wished to introduce vicarious liability by appropriate inference.

B. Section 107 of the IPC

The term “instigate” simply means to provoke, incite, encourage, or bring about something by persuasion. As given in Section 107’s three provisions, abetment may take the form of instigation, conspiracy, or deliberate assistance. Section 109 states that if the crime abetted is done as a result of abetment and no provision is made for the penalty of that abetment, the defendant will be punished with the sentence prescribed for the initial crime. In Section 109, the term “abetted” refers to the particular offence abetted.

The basic elements of section 107 of the Indian Penal Code, namely, that the applicant instigated or deliberately helped the accused in making sexually coloured remarks against the defendant, are strikingly missing.

C. Section 509 of the IPC

To constitute an offence under Section 509, it must be established that a woman’s modesty has been violated by a spoken phrase, expression, or physical behaviour. The offence is not established as defendant’s grievance is that the victim used objective or derogatory language against him.

D. Section 67 of the Information Technology Act, 2000

After carefully reviewing the allegations in the First Information Report and the material produced in the form of a charge sheet, the Court determined that there is no allegation or material that the Applicant published, transmitted, or caused to be published or transmitted in electronic form any material that is lascivious or appeals to prurient interest, or its effect is such that it seems to.

COURT’S RULING

The Hon’ble Court opined that a group administrator has no control over group members’ posts/action, unless it is shown that there was a common intention or pre-arranged plan between the member of a Whatsapp group and the administrator. Further in the absence of a legal liability accruing to the administrator, the Hon’ble Court exercised its power under Section 482 as observed in the case of State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal[2] and held that “we are satisfied that even if allegations in the First Information Report are accepted as correct, and considering the material in the form of charge-sheet on its face value, it does not disclose essential ingredients of offences alleged against the applicant under sections 354-A(1)(iv), 509 and 107 of the Indian Penal Code and section 67 of the Information Technology Act, 2000”. In view thereof, the FIR and the subsequent charge-sheet filed against the Applicant were quashed.

CONCLUSION

From the present ruling, it is apparent that without clear penal provision establishing vicarious liability, a WhatsApp group administrator cannot be found responsible for offensive material shared by a group participant. Criminal liability for inappropriate material would only arise for a group administrator when it has been established that there was a mutual purpose or premediated plan. However, it is pertinent to mention that the Court had acknowledged the group administrator’s responsibility towards maintaining decorum in a WhatsApp group conversation. In fact, is it too far-fetched to assume that the underlying intent to granting the administrative power of removing group members is to control the influx of unwanted/derogatory messages? Therefore, the Hon’ble Court’s ruling highlights another lacuna being overlooked in this digital age, which has become a complex blend of freedom of speech, privacy and control.

[1] https://faq.whatsapp.com/general/security-and-privacy/how-to-use-whatsapp-responsibly/?lang=en; accessed on May 26, 2021

[2] [1992 Supp.(1) SCC 335]

Ludo- A Game of Chance or Skill- Bombay High Court.

By Nihit Nagpal and Devika Mehra

The board game, LUDO, is the perennial nostalgic favourite from everyone’s childhood, having historic roots dating back to depictions and iterations of it in the cave paintings of Ajanta-Ellora, as well as in the Mahabharatha. While LUDO had its heyday in the 20th century, in the 21st, with the advent of gaming technology, board games as a genre took a backseat, while we were all glued to screens. However, board games took over these screens as well, as various companies brought in the virtual versions of the old-but-gold board games, of which LUDO was definitely one. The benefit of a virtual version of LUDO was that it now allowed everyone to play with their friends, sitting in different corners of the world. Especially during the recent COVID lockdowns, many were able to alleviate both boredom and fear and still stay connected remotely and have fun via the online platform of the childhood favourite game.

GAMES OF CHANCE vs. GAMES OF SKILL

Games, legally, are two fold and are hence categorized as “games of chance” and “games of skill”.

The main points of difference between the two can be explained as below:

| GAME OF CHANCE | GAME OF SKILL |

| Outcome is strongly influenced by some randomizing device, such as dice, spinning tops, playing cards, roulette wheels, or numbered balls drawn from a container. | Outcome is determined mainly by mental or physical skill, rather than chance. |

| May have some skill element to it, but chance generally plays a greater role in determining its outcome. | May have elements of chance, but skill plays a greater role in determining its outcome. |

| Based on the element of luck, coupled with skill to a certain extent. | Based on one’s knowledge and expertise of the subject. |

| One where success primarily depends on chance but is not altogether devoid of skill. | One in which success primarily depends on the superior knowledge, training, attention, experience, and adroitness of the player[1] |

| The element of chance predominates over the element of skill | The element of skill predominates over the element of chance |

Nonetheless, in each game, one element would predominate the other. Hence, games wherein skill predominates are termed as games of skill, and those wherein chance predominates, are termed as games of chance, and hence would attract the elements of the Public Gambling Act and its regulations. Section 12 of the Public Gaming Act[2] provides that the said act shall not apply to any “game of mere skill”, since the main objective of the act is to regulate and monitor those games played on chance.

Gambling- Skill or Chance?

The Hon’ble Supreme Court[3] has observed the definition of gambling as:

“the betting or staking of something of value, with consciousness of risk and hope of gain on the outcome of a game, a context, or an uncertain event the result of which may be determined by chance or accident or have an unexpected result by reason of the better’s miscalculations”.

Gambling has been defined[4] as something which involves not only chance, but also a hope of gaining something beyond the amount played. Gambling consists of consideration, an element of chance, and a reward. The Supreme Court also held that even though the most important aspect of gambling is chance, it does not mean that it is completely devoid of skill.[5] Hence, there are games which require skill, coupled with chance, up to a certain degree and such games are not illegal. It is imperative to mention here that the Public Gambling Act, 1867 does not expressly refer to “game of chance” and/or “game of skill” (the differentiation is being made here for the sake of argument).

It is the dominant element – ‘skill’ or ‘chance’ – which determines the character of the game. It has been held[6] [7] by several State High Courts that competitions wherein success depends on a substantial degree of skill are not ‘gambling’; and despite there being an element of chance, if a game is preponderantly a game of skill it will nevertheless qualify as a game of “mere skill”. Therefore, the expression “mere skill” may be considered to mean a substantial degree or preponderance of skill.

The Case of LUDO

Various app developers have brought out mobile game versions of LUDO through the Google Play Store / Apple AppStore, and some have even introduced their own modification to the game. One core commonality of the game of LUDO has been maintained in all the games in that they do not involve playing for financial stakes i.e. no real money was put at stake before playing this game. This was, however, found to not be the case with the Ludo Supreme App made by the private company, Cashgrail Private Limited. Accordingly, a petition seeking declaration was filed before the Bombay High Court in this regard by one, Mr. Keshav Ramesh Muley, a regional party worker.

The Petitioner has claimed before the Bench comprising the Hon’ble Justices S.S. Shinde and Abhay Ahuja that a declaration be made that “Ludo is a game of chance, and not a game of skill”, and therefore, the provisions of the Maharashtra Prevention of Gambling Act, 1887 would apply if the game is played for stakes.

In the Petition filed before the Hon’ble High Court, the Petitioner had highlighted the following facts leading to the filing of the said petition:

- The Petitioner has stated that he came across few young children playing this game on mobile phones and noticed the Indian Rupee Symbol on the screen which raised his suspicion. On enquiring, he learnt that money could easily be won in this game. On further researching, the Petitioner states that he found various videos streaming on websites which taught how to win money in the game.

- The Petitioner then went further to download the game and learnt that one could play the game by putting money at stake. One is required to link their bank account to the application and therein, one can deposit money in the application’s electronic wallet.

- The Petitioner has further explained that, LUDO being a 4 player game, each player is required to deposit Rs. 5/- as entry fees into the online mode of the game and the winner would take all the money, barring a certain amount that would get deducted by the application and go to the Company. Hence, the Petitioner has stated that “the prize money is not some notional or fictional winning but is real-time currency of value”.

- The Petitioner has then argued that since the makers of the game are retaining certain amount from this game, it shows that they are making profit from the game and hence, this qualifies as an offence under the Gambling Act, since there is no scope of skill in this game and is purely a game of chance.

- The Petitioner had approached the local police to register an FIR under Section 419[8] and 420[9] IPC in November 2020. However, the police had refused to register a case, which had led the Petitioner to approach the Metropolitan Magistrate’s Court with a private complaint. However, this too had been rejected holding (inter alia) that LUDO is a game of skill, not chance.

CONCLUSION

In India, States have the power[10] to make their own laws to curb gambling within their territory. While various States still choose to follow the (central) Public Gambling Act, 1867 to regulate gambling, various other States have brought into force their own local legislations to keep a strict watch on and curb (as far as possible) acts of gambling, having view of the menace that it could lead to if not regulated.

Under the Maharashtra local law (Maharashtra Prevention of Gambling Act, 1887), the Bombay High Court took notice of this petition filed by the Petitioner and called upon the State to file their reply to the Petition. The matter was thereafter listed on June 22, 2021 when the attorney appearing on behalf of the State of Maharashtra filed a report, signed by the Assistant Police Inspector, Shri Nitin Chavan, and the same was taken on record.

The matter now stands adjourned to July 20, 2021. It is now upon the Bombay High Court to determine whether in Ludo, chance predominates skill or skill predominates chance, which will define the fate of whether this beloved game would constitute gambling.

[1] K.R. Lakshmanan vs State of Tamil Nadu 1996 AIR 1153 , 1996 SCC (2) 226

[2] 12. Act not to apply to certain games.—Nothing in the foregoing provisions of this Act contained shall be held to apply to any game of mere skill wherever played.

[3] K.R. Lakshmanan vs State of Tamil Nadu 1996 AIR 1153 , 1996 SCC (2) 226

[4] Black’s Law Dictionary

[5] https://ssrana.in/corporate-laws/gaming-and-sports-laws-india/gambling-laws-india/

[6] State of Andhra Pradesh vs K.Satyanarayana & Ors. (1968) 2 SCR 387 , AIR 1968 SC 825

[7] State of Bombay vs Chamarbaugwala AIR 1957 SC 699, AIR 1957 SC 628

[8] Punishment for cheating by personation.—Whoever cheats by personation shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.

[9] Cheating and dishonestly inducing delivery of property.—Whoever cheats and thereby dishonestly induces the person deceived to deliver any property to any person, or to make, alter or destroy the whole or any part of a valuable security, or anything which is signed or sealed, and which is capable of being converted into a valuable security, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to seven years, and shall also be liable to fine.

[10] List 2, Seventh Schedule, Constitution of India

Related Posts

All you need to know about Online gaming business in India

Lockdown – A potential for the online gaming industry!!

THE RIGHT TO BE FORGOTTEN.

By Lucy Rana and Rima Majumdar

The very idea of privacy has seen been challenged by the widespread use of the internet. Privacy as such is very hard to enforce, as compared to pre-internet and social media times. Accordingly, the debate regarding the right to be forgotten has been raging on for a very long time, and has seen various landmark judgments and legislations in many parts of the world. This variation of the right to privacy, i.e. the right to be forgotten, has recently come up before the Delhi High Court also.

A Single Bench of the Delhi High Court recently heard a Writ Petition wherein the Petitioner had sought for the removal of a judgment from the platforms of Google, Indian Kanoon and vLex.in, in a case wherein he was an accused but was ultimately acquitted.

Jorawer Singh Mundy vs. Union of India & Ors.

In the case titled Jorawer Singh Mundy vs. Union of India & Ors.[1], Justice Pratibha M. Singh, dealt with the issue of one’s Right to Privacy and Right to be Forgotten, and the general public’s Right to transparency of judicial records.

BRIEF FACTS OF THE CASE

The case of the Petitioner is that he is an American citizen of Indian origin, who manages investments, deals with real estate portfolios, etc.

When he travelled to India in 2009, a case under the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (NDPS), 1985, was lodged against him. However, finally vide judgment dated 30th April, 2011, the trial court had acquitted him of all charges.

Thereafter, an appeal was filed challenging the order of the trial court, and vide judgment dated 29th January, 2013, a Single Judge of the Delhi High Court upheld his acquittal in Crl.A. No. 14/2013 titled Custom v. Jorawar Singh Mundy.

When the Petitioner thereafter went back to his home country, he faced significant hurdles in his professional life due to the fact that the judgment rendered by the High Court on appeal was available on Google for any potential employer to see, who wanted to conduct his background verification before employing him.

Due to the said issue, the Petitioner initially had requested Google India (Respondent No. 2), Google LLC (Respondent No. 3), Indian Kanoon (Respondent No. 4) and vLex.in (Respondent No. 5) to take down the said judgment. However, except for Respondent No. 5, none of the other Respondents acted upon the Petitioner’s request.

Therefore, the present Writ petition was filed, seeking directions to be issued to the Respondents to remove the said judgment from all the Respondents’ respective platforms, recognizing the Right to Privacy of the Petitioner, under Article 21 of the Constitution.

Balance the Right to Privacy of individual with the Right to Information of the public

The legal issue that the Hon’ble Court had to adjudicate in this particular matter was to balance the Right to Privacy of the Petitioner with the Right to Information of the public and maintenance of transparency in judicial records, if a Court order is removed from online platforms.

Relying on an interim order passed by the same Judge in an earlier civil suit tiled Zulfiqar Ahman Khan vs M/S Quintillion Business Media Pvt. Ltd. & Ors., CS(OS) 642/2018, and an order passed by the Orissa High Court in the case of Subhranshu Rout v. State of Odisha, BLAPL No.4592/2020, the Hon’ble Single Bench was of the prima facie view that the Petitioner is entitled to some interim protection, while the legal issues are pending adjudication before the Court.

Accordingly, Google India and Google LLC were directed to remove the judgment dated January 29, 2013 in Crl.A.No. 14/2013 titled Custom v. Jorawar Singh Mundy from their search results. Furthermore, Indian Kanoon was directed to block the said judgement from being accessed by using search engines such as Google/Yahoo etc., till the next date of hearing. The Union of India was directed to ensure compliance of the directions passed by the Court in the said order.

Case laws on Right to be forgotten

Although there have not been many cases decided by courts in India regarding this issue, the precedent appears to be uniform, except for one instance before the Gujarat High Court.

In 2016, in Civil Writ Petition No. 9478 of 2016 the Kerala High Court passed an interim order requiring Indian Kanoon to remove the name of a rape victim which was published on its website along with the two judgments rendered by the Kerala High Court in Writ petitions filed by her. The court recognised the Petitioner’s right to privacy and reputation, without explicitly using the term ‘right to be forgotten’.

Conversely though, in 2017 in the case of Dharamraj Bhanushankar Dave vs State Of Gujara, Special Civil Application No. 1854/2015, the Gujarat High Court dismissed a petition seeking “permanent restraint on public exhibition of judgment and order” on an online repository of judgments and indexing by Google. It was the case of the Petitioner that he had been acquitted of several offences by the Sessions Court and High Court and the judgment in question was classified as ‘unreportable’. The Court dismissed the petition on the grounds that the petitioner was not able to point out any provisions in law that posed a threat to his right to life and liberty, and that publication on a website did not amount to ‘reporting’ of a judgment since it is not a law report.

However, the Delhi High Court in the Zulfiqar case mentioned above, upheld an individual’s right to be forgotten. The Plaintiff in that case approached the Hon’ble Court seeking permanent injunction against the Defendants, who had written two articles against the Plaintiff on the basis of harassment complaints claimed to have been received by them, against the Plaintiff, as part of the #MeToo campaign. Although the Defendants had agreed to take down the news articles, the same had been republished by other websites in the interim. The Court recognising the Plaintiff’s Right to privacy, of which the `Right to be forgotten’ and the `Right to be left alone’ are inherent aspects, and directed that “any republication of the content of the originally impugned articles or any extracts/ or excerpts thereof, as also modified versions thereof, on any print or digital/electronic platform shall stand restrained during the pendency of the present suit.”

Back in 2020, the Orissa High Court in the Subhranshu Rout case, as mentioned above also, gave a detailed examination of one’s right to be forgotten in any context. In the said case, the Hon’ble High Court was deciding a bail application under section 439 of Cr.P.C, wherein the Petitioner, who was the accused in the FIR, had released certain objectionable images of the complainant on Facebook against her will. The Court questioned that although the statute prescribes penal action for the accused for such crimes, the rights of the victim, especially, her right to privacy which is intricately linked to her right to get deleted in so far as those objectionable photos, have been left unresolved.

The Court relied on cases decided in the European Union in order to discuss the issue of right to be forgotten. The aspect of right to be forgotten appears in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which governs the manner in which personal data can be collected, processed and erased. Recitals 65 and 66 and in Article-17 of the GDPR, vests in the victim a right to erasure of such material after due diligence by the controller expeditiously. In addition to this, Article 5 of the GDPR requires data controllers to take every reasonable step to ensure that data which is inaccurate is “erased or rectified without delay”. Interestingly, the Court commented that it cannot be expected that the victim shall approach the court to get the inaccurate data or information erased every single time, regarding data which is within the control of data controllers such as Facebook or Twitter or any other social media platforms.

Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021

It may be observed that the above mentioned comment of the Hon’ble Court resonates with the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, which was notified by the Government of India on February 25, 2021, and also provides for establishment and maintenance of Grievance Redressal Mechanisms by an intermediary operating (or looking to operate in India) mandatory.[2]

Rule 3(2) of the 2021 Rules provides that an intermediary shall appoint a Grievance Officer for handling grievances and complaints raised at least by Indian users (if such a mechanism is not already in place). This would include by prominently displaying the name and contact details of the Grievance Officer on its Website or Mobile Application, and by mentioning the method by which a complainant may be made to them by the aggrieved person.

The said sub-rule further provides that the role of the Grievance Officer is to:

- Acknowledge complaints received within 24 hours, and dispose of the same within 15 days;

- Acknowledge any order, notice or direction issued by a court or a government agency.

Furthermore, if the content is alleged to be exposing the complainant in a non-consensual manner, then the same has to be taken down within 24 hours of receiving such a complaint.

It also mandates implementing a mechanism for receiving such complaints which may enable the individual or person to provide details, in relation to such content or share the link for the said content.

This mechanism ensures that complaints are redressed expeditiously, especially those that are made by a specific individual alleging proliferation of his/her non-consensual images by a user of the said intermediary.

The Hon’ble Single Judge of the Orissa High Court also referred to the case of Google Spain SL & Anr. vs. Agencia Espanola de Protection de Datos (AEPD) & Anr., C-131/12[2014] QB 1022, wherein the European Court of Justice ruled that “the European citizens have a right to request that commercial search engines, such as Google, that gather personal information for profit should remove links to private information when asked, provided the information is no longer relevant. The Court in that case ruled that the fundamental right to privacy is greater than the economic interest of the commercial firm and, in some circumstances; the same would even override the public interest in access to information.” Click here about to learn more the case in detail

Importantly, the Orissa High Court in the Subranshu case recognized that in the absence of clear legislation, it is difficult to adjudicate on the practical limitations and technological nuances. However, the Hon’ble Single Judge mentioned that the Ministry of Law and Justice, on recommendations of Justice B.N. Srikrishna Committee, has included the Right to be forgotten, which refers to the ability of an individual to limit, delink, delete, or correct the disclosure of the personal information on the internet that is misleading, embarrassing, or irrelevant etc. as a statutory right in Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, which is yet to be notified.

Given that the case was a bail petition, the Court did not find it appropriate to direct social media platforms to take down the objectionable content identified by the petitioner. However, the Court did recognise that the petitioner’s right to privacy had been infringed and stressed on the need for appropriate legislation to provide redressal in these situations, especially in the context of protecting the modesty of women.

Coming back to the order of the Delhi High Court in the writ petition of Jorawer Singh, it may be pertinent to note that the direction given to Indian Kanoon is not of the nature of blocking access to the judgment entirely. The judgment would still be visible upon a search query on Indian Kanoon’s website, it is only de-linked from search engines, in essence increasing the effort it takes to find it. By doing the same, it ensures that judicial transparency is protected while acknowledging the rights of the Petitioner. After all, if a prospective employer is conducting a background check before hiring, they can hardly be expected to search on websites such as Indian Kanoon. That said, the possibility cannot be ruled out.

It would be interesting to see what the Delhi High Court finally decides on the said matter, and how it ensures a balance between the right to be forgotten and judicial transparency is maintained.

[1] W.P.(C) 3918/2021

Related Posts

India: Will judiciary recognize the emerging “right to be forgotten”

COMPENSATION FOR HOME-MAKERS OF THE NATION.

By Lucy Rana and Sanjana Kala

CASE ANALYSIS: KIRTI VS ORIENTAL INSURANCE CO LTD (2021) 2 SCC 166

Recently, the Supreme Court in the case of Kriti v/s Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. opined that while calculating the notional income in motor vehicle accidents, the deceased and non-earning members including homemakers should also be taken into consideration to arrive to a fair and just compensation. The apex court partly allowed the appeal from the judgment where the High Court had disallowed the future prospects awarded by the Motor Accident Claims Tribunal for a deceased victim who was a homemaker and further enhanced the awarded amount. The captioned judgment is a step forward towards negating the notion that homemakers do not contribute any economic value to the society and cannot share the same pedestal of that of a bread earner.

Facts

- The deceased couple, Vinod and Poonam, while commuting on a motorcycle in Delhi at around 7 AM on April 12, 2014 were hit at an intersection by a Santro car bearing registration ‘DL 7CA 1053’. The impact immediately incapacitated both the deceased and they soon passed away from craniocerebral damage and hemorrhagic shock caused by the accident’s bluntforce trauma;

- An FIR was registered under Sections 279 and 304 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (hereinafter, “IPC”) against the driver and the statement of an independent eyewitness (Constable Vishnu Dutt) was recorded, which evidenced rash driving and negligence on part of the cardriver. Subsequently, a claim petition was filed under Section 166 of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 by the two toddler daughters and septuagenarian parents of the deceased.

- This was contested by the driver and owner claiming that the deceased were themselves driving negligently and the accident had been a result of their very own actions. Two witnesses were examined by the appellantclaimants and none by the respondents. The insurance company (Respondent No. 1) offered as settlement a compensation of INR 6.47 lakhs for the death of Poonam and INR 10.71 lakhs for Vinod.

Procedural History

- The Motor Accident Claims Tribunal, Rohini (hereinafter, “Tribunal”) took note of the chargesheet filed against the driver in the criminal case and also his failure to step into the witness box. Relying on the strong testimony of the independent witness, it was concluded that the cardriver had indeed been driving rashly and thus liability ought to be fastened on the respondentinsurer.

- The Tribunal awarded a motor accident compensation of INR 40.71 lakhs on December 24, 2016 under Section 168 of the Motor Vehicle Act, 1988 (“MV Act”). The quantum of compensation was calculated as below:

| AGE-MULTPLIER | COMPENSATION FOR LOSS OF LOVE AND AFFECTION | COMPUTATION OF LOSS OF DEPENDENCY | FUTURE PROSPECTS | PERSONAL EXPENSES | CONTRIBUTION TO HOUSEHOLD |

| Ages of Poonam and Vinod were determined as 26 and 29 years respectively. An age multiplier of 17 was adopted. | Rs 2.50 lakhs was given for each deceased

as compensation for loss of love and affection, estate, and funeral charges |

The minimum wage in Delhi was adopted for computation of loss of dependency for Vinod (owing to his father’s unsubstantiated claim of him being a teacher) | An additional 25% income was accounted for future prospects of Poonam | 1/3rd of Vinod’s salary was deducted towards personal expenses | No income under this head was computed |

| DECISION OF TRIBUNAL: Thus, the Tribunal awarded a total sum of INR 40.71 lakhs for both deceased to the claimants | |||||

This computation was challenged by the RespondentInsurer before the High Court and the quantum of compensation was calculated as below:

| COMPUTATION OF LOSS OF DEPENDENCY | FUTURE PROSPECTS | PERSONAL EXPENSES | CONTRIBUTION TO HOUSEHOLD |

| Minimum wage charged as per the state of Haryana (established residence of the deceased) and not the state of Delhi Therefore the High Court adopted the lowest minimum wage applicable for unskilled workers in Haryana | Future prospects were denied

to both deceased |

1/3rd of Poonam’s income was

deducted towards personal expenses

|

Given the totality of circumstances and

Poonam’s contribution to her household, 25% additional gratuitous income was added to her salary |

| DECISION OF HIGH COURT: Thus, the High Court reduced the total compensation to a total sum of INR 22 lakhs for both deceased. | |||

The decision of the High Court was challenged by the claimants before the Supreme Court;

Issues before the Supreme Court

- Should the subsequent death of the deceased’s mother be taken into consideration to calculate the share of deduction of personal expense?

- Should minimum wages of the lowest tier be used to calculate the monthly income of the deceased?

- Should payment for future prospects be made to the deceased where there is no proof of any employment or fixed salary?

Decision of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court allowed the appeals in part and increased the compensation awarded by the Delhi High Court to the claimants-appellants by INR 11.20 Lakhs, making it a total sum of INR 33.30 Lakhs based on the following grounds:

(I) Deduction for Personal Expense

- The Apex Court settled the fact that the time of death there were 4 dependents of the deceased and the subsequent death of the deceased’s mother ought not to be the reason for the deduction of the compensation. The legal claims crystallize at the time the accident has occurred and does not take into the account of the changes that occur in due course of the proceedings.

- The accident also led to the death of the unborn child of the deceased couple and thus the appropriate deduction for personal expenses of both should be 1/4th and not 1/3rd.

- The lower compensation conceded by the counsel for the Appellants does not bind the parties, as it is legally settled that advocates cannot throw away legal rights or enter into arrangements contrary to law.

(II) Assessment of monthly income

- Considering the reasonable standard of living of the deceased and their family, as evidenced by the use of a motorcycle for commuting, adoption of the lowest tier of minimum wage while computing the income is not justified. Monthly income should be calculated in such a manner that the existing standard of living of the dependents are reserved. Thus the minimum wage of a skilled worker should be used to calculate the monthly income.

(III) Additional Future Prospects

- The court relied on the judgment passed by the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court in the case of National Insurance Co Ltd v. Pranay Sethi[1] wherein the court held “In case the deceased was selfemployed or on a fixed salary, an addition of 40% of the established income should be the warrant where the deceased was below the age of 40 years”.

- The court rejected the contention of the respondent-insurer that future prospects cannot be allowed in case of notional income. The Supreme Court relied on the observations of this court in the case of Hem Raj v. Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd.[2] held “We are of the view that there cannot be distinction where there is positive evidence of income and where minimum income is determined on guesswork in the facts and circumstances of a case .Both the situations stand at the same footing. Accordingly, in the present case, addition of 40% to the income assessed by the Tribunal is required to be made.”

- Therefore, Vinod and Poonam (29 years and 26 years respectively), both being below the age of 40 were granted future prospects calculated to the tune of 40% of their established income.

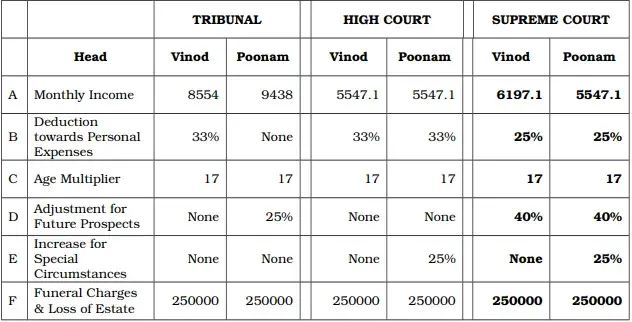

A comparative table of revised compensation after suitable increases was depicted by the Supreme Court as follows:

Analysis and Commentary

Justice N.V. Ramana took the opportunity to explain the rationale behind the computation of notional income in case of a homemaker wherein he said:

“it is an acceptance of the idea that these activities contribute in a very real way to the economic condition of the family, and the economy of the nation, regardless of the fact that it may have been traditionally excluded from economic analyses”

Justice N.V Ramana also cited the judgment of Arun Kumar Agarwal v. National Insurance Co. Ltd[3], where the court had held:

“In India the Courts have recognised that the contribution made by the wife to the house is invaluable and cannot be computed in terms of money. The gratuitous services rendered by the wife with true love and affection to the children and her husband and managing the household affairs cannot be equated with the services rendered by others. A wife/mother does not work by the clock. She is in the constant attendance of the family throughout the day and night unless she is employed and is required to attend the employer’s work for particular hours. She takes care of all the requirements of the husband and children including cooking of food, washing of clothes, etc. She teaches small children and provides invaluable guidance to them for their future life.”

The notional income of the homemaker can be determined by various methods. Some of the methods were highlighted by a Division Bench of the Madras High Court in the case of Minor Deepika[4] which held:

“One is, the opportunity cost which evaluates her wages by assessing what she would have earned had she not remained at home, viz., the opportunity lost. The second is, the partnership method which assumes that a marriage is an equal economic partnership and in this method, the homemaker’s salary is valued at half her husband’s salary.”

The 2021 judgement also took into the consideration of statistics in India wherein according to the 2011 Census, nearly 159.85 million women stated that “household work” was their main occupation, as compared to only 5.79 million men. The recently released Report of the National Statistical Office of the Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, Government of India called “Time Use in India 2019”, which is the first Time Use Survey in the country, and collates information from 1,38,799 households for the period January, 2019 to December, 2019, reflects the same gender disparity.

The key findings of the survey suggest that, on an average, women spend nearly 299 minutes a day on unpaid domestic services for household members versus 97 minutes spent by men on average. Similarly, in a day, women on average spend 134 minutes on unpaid caregiving services for household members as compared to the 76 minutes spent by men on average. The total time spent on these activities per day makes the picture in India even clearer: women on average spent 16.9 and 2.6 percent of their day on unpaid domestic services and unpaid caregiving services for household members respectively, while men spent only 1.7 and 0.8 percent in comparison.

Conclusion

Despite all the above, the conception that housemakers do not “work” or that they do not add economic value to the household is a problematic idea that has persisted for many years and must be overcome. Therefore, fixing the national income of a homemaker is of special significance as it will give recognition to the work, labor, and sacrifices of homemakers. In addition to that, it is in furtherance of India’s obligations as being a signatory of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights wherein as per Article 7 it is highlighted that ‘All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law’. Moreover, the captioned judgment will promote and reinstate the principles of social equality and dignity of all, as envisaged in the Constitution of India.

However, there can be no exact calculation or formula that can magically ascertain the true value provided by an individual gratuitously for those whom they hold near and dear. The attempt of the Court in such matters is therefore towards determining, in the best manner possible, the truest approximation of the value added by a homemaker for the purpose of granting monetary compensation.

[1] (2017) 16 SCC 680

[2] (2018) 15 SCC 654

[3] (2010) 9 SCC 218

[4] National Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Minor Deepika rep. by her guardian and next friend, Ranganathan, 2009 SCC OnLine Mad 828